Suzanne BearnTechnology reporter

XYZ movies

XYZ moviesFinding international films that can appeal to the US market is an important part of what XYZ Films does.

Maxime Cottray is the Chief Operating Officer of an independent studio in Los Angeles.

He says the U.S. market has always been difficult for foreign-language films.

“It was only accessible to coastal New York audiences through arthouse films,” he says.

Part of this is a language problem.

“America is not a culture that grew up with subtitles or dubbing, as Europe did,” he notes.

But this language barrier may be easier to overcome with the help of a new artificial intelligence-driven dubbing system.

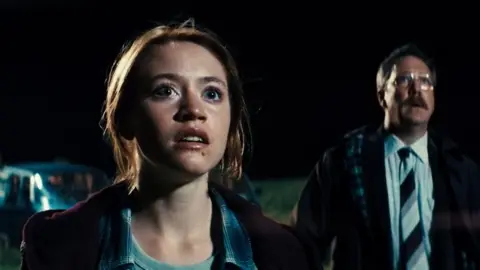

Audio and video from the recent Swedish sci-fi film Watch the Sky have been uploaded to a digital tool called DeepEditor.

He manipulates the video to make it seem like the actors are genuinely speaking the language in which the film is shot.

“When I first saw the results of this technology two years ago, I thought it was good, but seeing the latest version, it's amazing. I'm convinced that if the average person saw it, they wouldn't notice it – they would assume they were speaking a language,” says Mr Cottray.

The English version of Watch The Skies was released in May in 110 AMC theaters in the United States.

“To contextualize this result, if the film had not been dubbed into English, it would never have made it to US theaters in the first place,” says Mr Cottray.

“American audiences were able to see a Swedish independent film that would otherwise only have been seen by a very niche audience.”

He says AMC plans to do more releases like this.

Irreproachable

IrreproachableDeepEditor was developed by Flawless, headquartered in Soho, London.

Writer and director Scott Mann founded the company in 2020, having worked on films including Heist, The Tournament and The Final Score.

He felt that traditional methods of dubbing international versions of his films did not quite match the emotional impact of the originals.

“When I worked on 'The Heist' in 2014 with a brilliant cast, including Robert De Niro, and then saw it translated into another language, that's when I first realized that it's no wonder that film and television don't do well because the old world of dubbing really changes everything in a film,” says Mr. Mann, now based in Los Angeles.

“It’s all out of sync and executed differently. And from a purist filmmaking perspective, the rest of the world sees a much lower quality product.”

Irreproachable

IrreproachableFlawless has developed its own face identification and modification technology based on a method first presented in a research paper in 2018.

“DeepEditor uses a combination of facial recognition, facial recognition and landmark detection. [such as facial features] and 3D facial tracking to understand an actor's appearance, physical actions and emotional state in every frame,” says Mr. Mann.

The technology can preserve the original performances of actors in different languages without reshoots or re-recording, reducing costs and time, he said.

According to him, “Watch the Sky” was the world's first full-length feature film with completely visual dubbing.

Not only does DeepEditor make it seem like an actor is speaking a different language, but it can carry over the best performance from one take to the next or replace a new line of dialogue while preserving the original performance with its emotional content.

The global film dubbing market is expected to grow from US$4bn (£3bn) in 2024 to US$7.6bn by 2033, thanks to the rapid rise of streaming platforms such as Netflix and Apple. according to the report according to Business Research Insights.

Mr. Mann won't say how much the technology costs, but says it varies depending on the project. “I'd say it costs about a tenth of the cost of filming or altering it any other way.”

His clients include “virtually all the really big streamers.”

Mr Mann believes the technology will allow films to be seen by a wider audience.

“There are so many incredible types of film and television that English-speaking people never watch because many people don't want to watch them dubbed and subtitled,” Mr. Mann says.

The technology is not intended to replace actors, says Mann, who says voice actors are used rather than replaced with synthetic voices.

“We found that if you're making tools for actual creative people and artists themselves, this is the right way to do it… they get sort of power tools to create their art that can be used in the finished product. “It's the opposite of a lot of the approaches that other tech companies are taking.”

Nathan Dvir

Nathan DvirHowever, Neta Alexander, assistant professor of film and media at Yale University, says that while the promise of wider distribution is enticing, using AI to reconfigure performances for non-local markets risks undermining the specificity and texture of language, culture and gesture.

“If all foreign films are adapted to look and sound like English, audiences' relationships with foreigners become increasingly mediated, synthetic and sanitized,” she says.

“This may hinder intercultural literacy and disincentivize support for subtitled or original language screenings.”

Meanwhile, she said, the shift in closed captioning, a key tool for language learners, immigrants, deaf and hard-of-hearing viewers and many others, is raising accessibility concerns.

“Closed captioning is not just a workaround; it is a method of maintaining the integrity of both visual and audio storytelling for different audiences,” says Professor Alexander.

Replacing this with automated mimicry, she says, suggests a worrying turn toward a commodified and monolingual film culture.

“Rather than asking how to make foreign films more accessible to English-speaking audiences, we should be asking how to create an audience that is willing to watch diverse cinema on its own terms.”