This leaves the city with few local food options. Kakisa is tiny, with only about forty inhabitants living in an area of less than one square kilometer. The community typically relies on the towns of Fort Providence or Hay River, each about an hour away, for food, fuel, medical care, police and emergency services.

This distance is usually not a problem for many local residents. But Kakisa's remote location makes it particularly vulnerable to wildfires. In 2014, a fire occurred just meters from the village, forcing residents to flee. Still charred treetops poke out from the growing bushes along the only road leading into or out of town.

“We've almost lost a community,” says Lloyd Chicot, a longtime Kakisa leader and chief of Ka'agi Tu First Nation. “People were crying and stuff like that, it was very touching to see.”

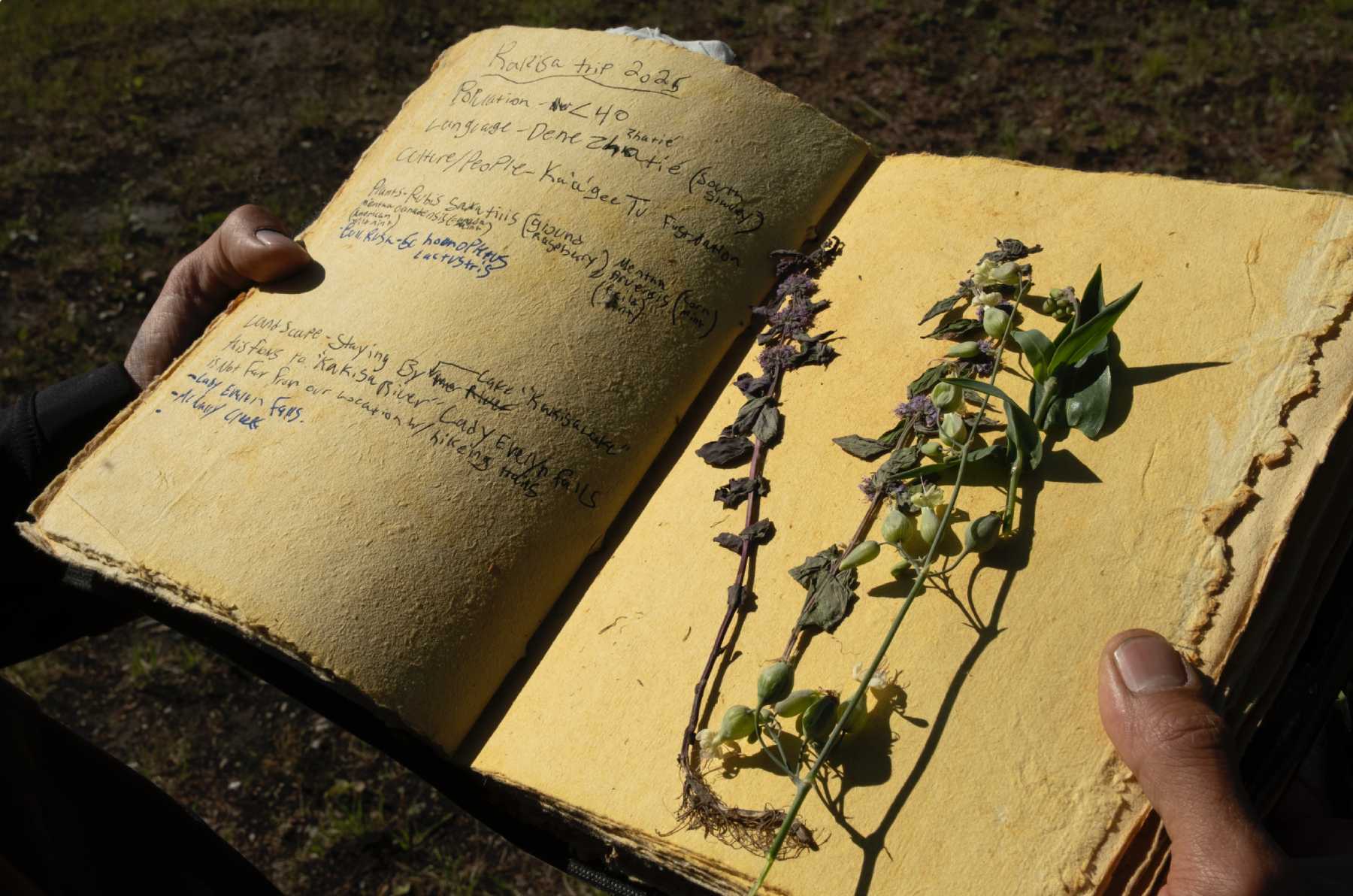

Elong before the disaster As a result, Kakisa began a movement towards sustainable food systems. Before the 2014 wildfire, Chicot called Andrew Spring, Canada Research Director for Sustainable Northern Food Systems at Wilfrid Laurier University. Together, they applied for a federal Climate Change Adaptation grant—money earmarked for Indigenous and remote communities to develop programs or resources for people whose traditional ways of life are impacted by climate-related events. One of their first priorities was to start growing food locally so that the city could at least feed itself if it were ever cut off from surrounding communities again.

Kakis's garden now occupies an area approximately equal to two neighboring tennis courts. Potatoes, lettuce, cabbage, beans and carrots grow throughout the summer. Next to them grow beds of strawberries and Iranian berries. Tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers are grown in two small greenhouses. In the event of an emergency, the amount of food produced could easily feed the population for days, perhaps weeks.

Similar scenes have emerged in other northern communities with garden or greenhouse projects, including Inuvik, NWT, and Naujaat and Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, all of which are either just above or north of the Arctic Circle. But here, as in Kakis, the real task is not necessarily sowing the seeds. This keeps the garden running.

TStokes rental, One of the workshop participants works at Aurora College in nearby Fort Smith and runs a community garden there. He calls himself a “northern bush boy” but says his greatest passion is growing food, which he says has helped him overcome his battle with addiction. What he says started as a plan to grow marijuana turned into a love of growing flowers and then vegetables.

Stokes' recovery through agriculture is an unusual story in northern communities. The garden he manages is located between the former mission and the boarding school. He prefers the term “food security” to “agriculture” because the latter can remind elders of the colonial destruction of their lands.

For his part, Spring is familiar with the views of the non-Indigenous scientists from Southern Canada who run the garden at Kakisa. He also knows that community gardens in the North often fail after the people who create them leave town or run out of funding. Poor soil, low yields, lack of accessible infrastructure, equal interest in government support and lack of skilled labor add to the challenges of maintaining community gardens.

“If we had left, I don’t think this project would have been sustainable,” he says. “It’s just another administrative burden for communities that are trying to stay afloat.”

Ruby Simba, band chief of the Kaagi Tu First Nation, says it has been difficult to train and retain workers for available jobs in the community, let alone convince residents to spend their free time tending or harvesting their gardens. While she's frustrated by the lack of interest, she admits one factor may be that some of the produce the summer students plant – such as squash and cabbage – is unfamiliar to locals. And since the garden is largely maintained by people outside the community, “it's not the community's business. So we have to fix it somehow.”