WITHScientists who study volcanoes have long believed that rising magma, rich in gas bubbles, would quickly reach the top of a volcano and erupt.

But famous eruptions such as Quizapu in Chile and Mount St. Helens in Washington state do not fit this pattern. Between 1846 and 1847, Quizapu carefully unloaded one of the largest lava flows ever recorded in South America, leaving behind piles of rock covering about 20 square miles.

And a few months before the nine-hour eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, something strange happened: Lava, filled with gas and seemingly ready to explode quickly, instead flowed slowly inside the volcano's cone. The powerful explosion only occurred when an earthquake and the resulting avalanche occurred, causing the northern slope of the mountain to collapse. (This released the pressurized gases inside the volcano, causing magma from below the surface to rise upward and erupt into the air.)

Now researchers say they have discovered a kind of pressure release valve that allows thick, gas-rich lava to slowly escape. paper published in the magazine Science.

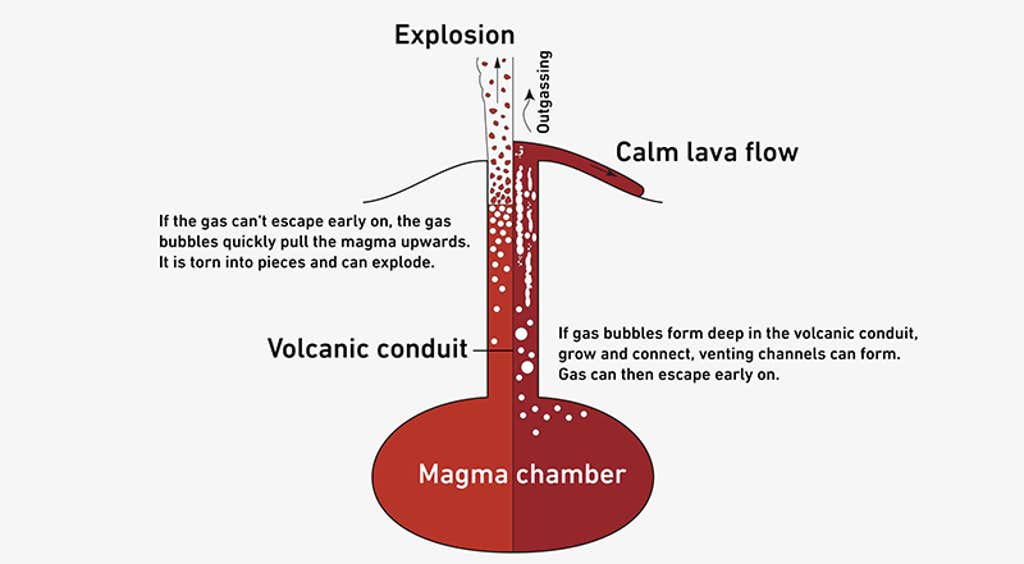

Gas bubbles were thought to occur when magma rises in volcanoes and the surrounding pressure decreases—much like when opening a bottle of champagne, the bubbles quickly push a fizzy magma mixture toward an explosion.

But in some cases, bubbles can form inside a tube-like channel, called a conduit, through which magma rises upward from an underground reservoir before being released as lava. Once deep inside the pipeline, these bubbles can coalesce and create channels for gas to escape before pressure builds.

“We can thus explain why some viscous magmas flow softly rather than explode despite their high gas content—a mystery that has puzzled us for a long time,” said study co-author Olivier Bachmann, a volcanologist at ETH Zürich in Switzerland, in his paper. statement.

Read more: “The sound was so loud that it circled the Earth four times»

This early bubbling occurs due to shear forces. This process can be compared to stirring honey. At the edge of the jar, due to greater friction, the honey moves more slowly than the sweet liquid in the center. Likewise, friction in a volcano conduit is higher along the edge than in the center. It “essentially 'kneads' the molten rock, creating gas bubbles” deep in the pipeline, according to the statement.

The team discovered this phenomenon by simulating volcanic activity in the laboratory by saturating a thick liquid simulating molten rock with carbon dioxide and then applying a shear force to the substance.

Bachmann now hopes that volcano models will better account for shear forces, which will help paint a clearer picture of the potential hazards of volcanoes.

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Main image: Aaron Rutten/Shutterstock