SAMAD AL-SHAN, Oman — On their final morning together in April of last year, two elderly sheikhs in a white Mercedes drove through a palm-tree-lined ravine to pay their respects at a funeral.

The two local leaders were cousins and best friends, traveled the world together and prayed at the same mosque. They lived on the same block in Samad al-Shan, a village amid the rocky hills south of Muscat that was built along one of hundreds of wadis — normally dry riverbeds — in one of the most water-scarce countries in the world.

Floods in this part of Oman, while rare, are not unheard of. Elders remembered that villagers used to fire guns to alert those downstream that water was coming. But as sheikhs Saif and Naser al-Mawaly drove through the date palm groves that morning, they had little warning beyond the steadily darkening sky that more than a year’s worth of rain would soon fall on their village.

“No one expected this,” said Saif’s son Yahya, an engineer. “It was the strongest storm of their entire lives.”

The storm system first dropped the most rain the United Arab Emirates had seen since records began 75 years earlier. It swamped Dubai’s subway, flooded its airport (the second-busiest in the world) and led to a remarkable greening of the desert visible from space months afterward.

It then swept across the coastal kingdom of Oman, home to some 5 million people — the latest battering storm to strike here in the past two decades, bringing calamity to communities along Oman’s wadis, the channels that run to the sea from countless wrinkles in the mountainous interior.

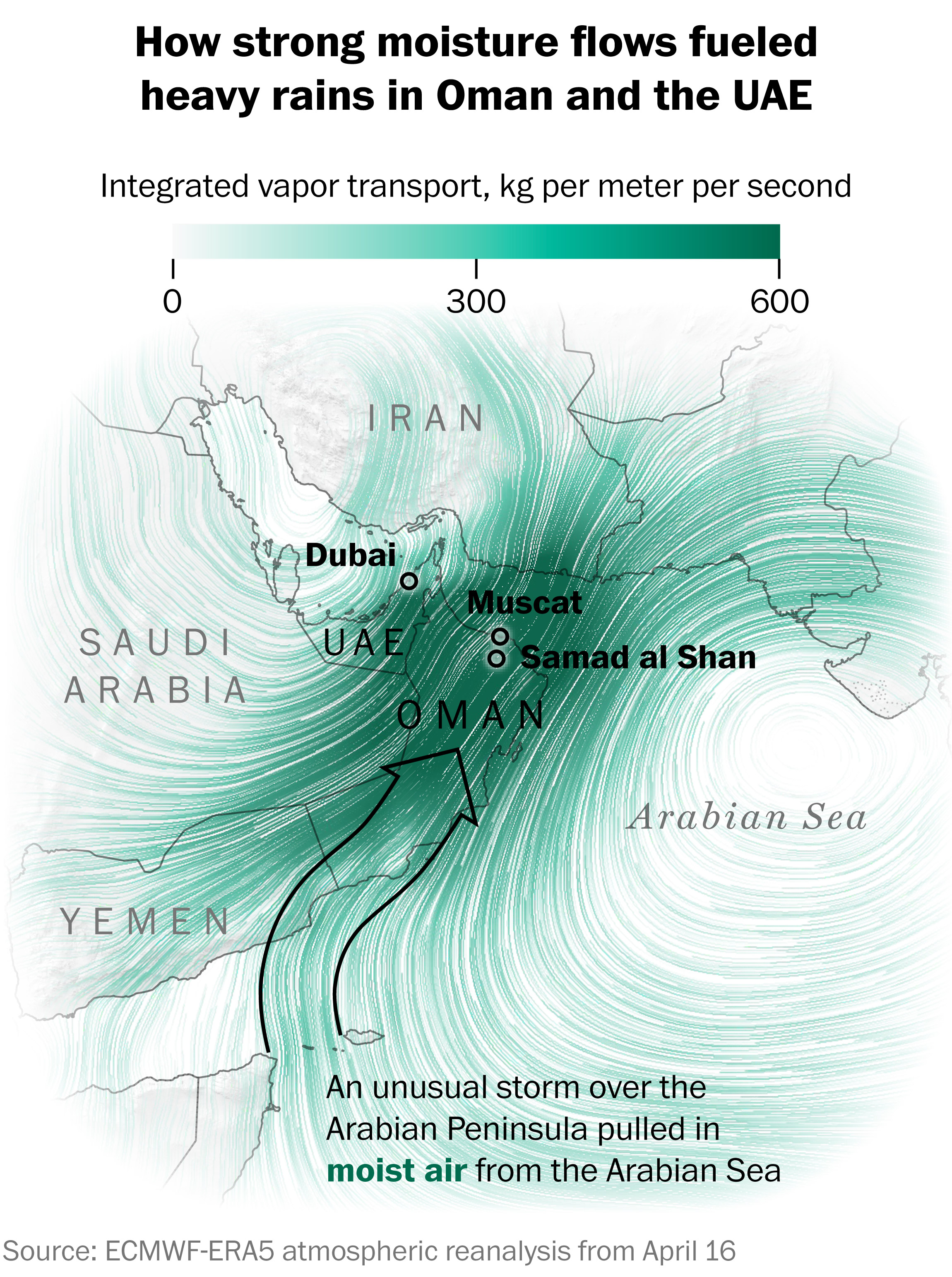

In one of the most arid places on the planet, extreme rainfall is becoming a recurrent source of catastrophe. A dramatic atmospheric shift is moving more moisture onto the shores of the northern coast of Oman, according to a Washington Post investigation of global atmospheric data. Here, the strongest plumes in the sky are surging at rates more than 1.5 times the global average.

Oman and its neighbors, relatively unaccustomed to the torrents becoming more common, have often been caught unprepared. For these oil-rich monarchies that prize order and stability, the shock wrought by such flooding has forced a reckoning with their changing environment. In response, they have embarked on a building spree of dams, culverts, evacuation sites and massive stormwater tunnels — seeking to engineer defenses to the growing problem of extreme rain.

“We’re trying to change the scale of how we manage rain,” said Fahd al-Awadhi, a civil engineer who directs drainage and recycled water projects with the Dubai municipality.

In Samad al-Shan, the historic rains left a residue of outrage and grief, particularly among residents who feel the government should have done more to warn and protect them. The storm forced residents into terrifying split second dilemmas — save themselves or help others? The controversial decision by authorities to keep students at school remains contested nearly two years later.

Yousuf al-Mawaly, Saif’s brother and an Islamic studies teacher at a local middle school, had been told to go home as the storm moved in, even as 855 students at the al-Hawari Bin Mohammed Azadi school were kept on-site.

Ten of the students would not survive the day.

Driving home that morning with a colleague, Mawaly noticed the sky had grown so dark that streetlights flickered on. When the rain unleashed, it pounded down so ferociously that he was forced to pull over. He had never seen such a rain.

“The car started shaking,” Mawaly recalled. “I became very worried at that moment that if the rain smashed through the windshield, we were going to die.”

Meanwhile, silty brown floodwaters swept around the sheikhs’ white Mercedes near the Bait al-Khabib castle — a 19th-century stone fort turned museum filled with artifacts dating back more than 5,000 years.

Residents of Samad al-Shan were familiar with water running through the channel. Many traditionally kept two homes here — one under the palm fronds in the heat of summer, another in the foothills out of harm’s way in winter rains. But many were shocked by how quickly the wadi transformed into a raging river.

Saif, 78, stepped from the vehicle as Naser, 77, struggled to extricate himself. Onlookers shouted at Saif to move to higher ground as he tried to pull his friend from the car.

With the roaring floodwaters tugging at him, Saif called his son.

“I don’t think there’s anything that can be done for us,” he said.

More frequent cyclones

In June 1890, a tropical cyclone roared ashore in the al-Batinah region on the north coast of Oman, leaving behind a path of destruction and killing more than 700 people. Over the next century, such hurricane-strength storms that formed in the Arabian Sea or the Bay of Bengal rarely made landfall in Oman.

In the 126 years between 1881 and 2007, just six hurricane-strength storms hit Oman or came within 60 miles of the country, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Then, the frequency started to change.

Cyclone Gonu crashed into the capital city of Muscat in 2007, bringing a record-breaking moisture plume over the capital, killing about 50 people and causing more than $4 billion in damage.

At least four more hurricane-strength storms made landfall in Oman in the past 15 years.

“After 2007, they kept coming,” said Khalid al-Jahwari, a meteorologist and lecturer at Sultan Qaboos University in Muscat. “Now on a yearly basis, cyclones come close to our coast.”

Jahwari — also the former assistant director of Oman’s national multi-hazard early-warning center, the office that tracks such storms — was at his home in the al-Batinah region when Category 1 Cyclone Shaheen made landfall in October 2021. The winds thrashed the palm trees in his yard and knocked out power. He spent that night huddled in the dark with his children as floodwaters poured into his home and couches drifted around the living room.

“It was very ugly,” he recalled. “We lost so much.”

Wide swaths of Oman receive less than 4 inches of rain on average a year, among the least of any nation in the world. Driving through the countryside reveals stunning expanses of rock and sand. Most of the drinking water for the population comes from desalination plants that filter ocean water. Without any major year-round rivers or natural freshwater lakes, many communities are built along wadis, which often have springs or accessible groundwater, and fill when it rains.

But as the climate has warmed, and offshore storms soak up more moisture from heated seas, the amount and distribution of rain are changing. While the number of rainy days has decreased, extreme events occur more often, pushing overall rainfall totals higher. The Post’s analysis found the strongest moisture plumes have greatly increased the chance for heavy rainfall across Oman, and have intensified over the past three decades. These wetter storms are dropping more rain into wadis, leading to more flash flooding and destruction.

“Before, no one was talking about flooding in Oman,” said Ghazi al-Rawas, the dean of research at Sultan Qaboos University. “They didn’t think there was any problem.”

Rawas had been drawn to his relatively unstudied field during graduate work at Boston University. He pored over satellite images of Oman, looking for clues about which wadis had the highest potential for flash flooding. As a civil engineering professor in Muscat watching storms intensify, he applied for grants in 2011 and 2016 to develop tools to help predict floodwater behavior. Both times the government rejected his proposals.

“Then Shaheen came,” he said.

The 2021 cyclone dropped 18 inches of rain on parts of the north coast, more than six times the annual average. It sent water coursing through Wadi al-Hawasinah, a rocky gorge two hours northwest of the capital, at the height of a three-story building. The water overtopped a dam, destroyed more than 300 houses and inundated a coastal area home to about a quarter of the population.

Rawas’s research project soon ranked as the sultanate’s No. 1 national priority within his university.

Since then, Rawas and his graduate student, Badar al-Jahwari, an official at the ministry of agriculture, fisheries wealth and water resources, have traveled the length of Wadi al-Hawasinah, used drones to map its ever-changing topography, and worked to develop a complicated model to answer a simple but urgent question: When the forecast says rain, how much water will show up in the wadi?

“The information we have right now is only from the weather forecast,” Rawas said. “But knowing the rainfall is not enough.”

One reason the predictions are hard is because of the way rain behaves in a desert. Rather than a steady drizzle over a wide expanse, research has shown that rainfall in arid areas tends to be highly localized. A slight change in storm track could mean a wadi expected to flood might stay completely dry.

In Oman, rainstorms also tend to be front-loaded, more than in wetter parts of the world. In their analysis of 8,000 storms over more than 20 years across 69 rainfall stations, Rawas and Jahwari found that half of the rain falls within the first 90 minutes of a 24-hour storm.

“We receive a huge amount of water in a very short time,” Rawas said.

Those intense but short-lived bursts of rainfall in one place can quickly overwhelm the desert’s ability to absorb water.

Rawas and Jahwari drove along Wadi al-Hawasinah into the foothills of the al-Hajar al-Gharbi mountains on a November day when it hadn’t rained in eight months. They stopped at some of the rainfall collection stations, with radar equipment linked to gauges to measure water flow during floods.

Wadi al-Hawasinah spans hundreds of feet across in some places, with a watershed encompassing 145 square miles — one of Oman’s medium-sized channels. Before the flood, Jahwari and his family would picnic here on weekends, amid the palm fronds and bushy sidr trees that can live for hundreds of years. But the flood scoured away almost all this vegetation.

“The Shaheen cyclone took everything from the wadi,” Jahwari said. “Before and after, it’s totally different.”

Now the rocky canyon is scattered with remnants of washed-out roads and culverts. Goats wander amid downed palm tree trunks.

Rainy days are still so rare that people often celebrate their arrival. Kids and parents rush outside. Some try to swim or drive across the channel, unfamiliar with the risks of fast-moving water. As the scientists drove past clusters of homes built deep in the channel, they worried these could be the next flood victims.

“People still think wadis are like they were before,” Rawas said. “But now the wadi is different than 30 years ago.”

Both men have a keen awareness of the growing storms to come. Rawas, a slight, bespectacled man with a courtly charm, has served on Oman’s negotiating team at the United Nations annual climate summits. He was the principal investigator for the country’s second climate action plan, submitted in 2021, which warned of the inescapable impacts of worsening storms.

For his dissertation, Jahwari analyzed rainfall records over several decades at 88 stations in northern Oman. While his work is yet to be published, he said preliminary results show storms in Oman are bringing more rain, more often.

“This shift toward more concentrated, high-intensity storms is consistent with the flash-flood impacts observed in recent years,” he said.

On a recent day, Jahwari visited al-Khaburah, the coastal district in the floodplain inundated during Shaheen. At the area’s old souk, a historical site along the wadi, damaged shops have been closed since the storm. Along a beach, massive slabs of reinforced concrete were half submerged in the waves, torn from somewhere upstream.

Nearby, a group of construction workers were rebuilding a house on a bank that Jahwari knew was eroding rapidly.

“They’re building again in the wadi,” he said. “People are not learning.”

Building to outpace rushing waters

Across the border in Dubai, the building is taking place out of sight. Two hundred feet below Sheikh Zayed Road, a multilane boulevard that carves a canyon through Dubai’s high-rise skyscrapers, massive machines have been boring tunnels beneath the earth.

As audacious as anything on the surface, the Emiratis’ underground ambitions are testing whether money and engineering can subdue the unruly forces of nature.

When complete, an 80-foot-diameter main tunnel shaft, along with its branching tentacles, will run for more than 120 miles. This underground network is a key part of the Tasreef Project, an $8 billion effort to funnel runoff from ever larger rainstorms to the sea, and curb the flooding that snarled air and road traffic last year in a key hub for the Middle East.

“When you talk about climate change — this is a reality that we’re living now,” said Awadhi, who oversees stormwater infrastructure in Dubai.

While planning that effort had been underway before the April 2024 storm, that downpour accelerated work and validated the decision to invest in a drainage system built for the next century of intensifying storms, authorities said.

After that downpour, the most rain ever recorded in the city, property insurance rates spiked by some 15 percent. Dubai authorities identified 14 critical areas that flooded, with blocked roads and swamped infrastructure. The Dubai airport canceled more than 1,000 flights.

“Now people are more open to consider these kinds of threats from extreme weather, which was not the case before this one,” said Diana Francis, a climate scientist at Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi, whose research estimated a storm of this magnitude is up to 30 percent more likely because of global warming.

Awadhi traveled with his team to cities like Tokyo, Singapore and New York to learn how they manage rain. Many places, he said, have infrastructure designed to accept a 25 percent chance of flooding each year. Dubai is aiming to engineer a stormwater system that would only have a 2 percent chance of flooding, he said.

Dubai authorities consider the stormwater system expansion one of the most significant infrastructure investments in its modern era. And after analyzing the past century of rainfall data, they believe more extreme rains are coming.

“As a trend, you will see it is increasing,” Awadhi said.

The scale of Dubai’s ambitions to solve flooding are visible at the Deep Tunnel — an early phase of the stormwater buildout located at the Jebel Ali port, a dusty industrial area in the southern part of the city.

A vast subterranean silo is the terminus of one of the largest gravity-fed stormwater tunnels in the world. Massive, belowground pumps push water that’s been collected up through pipelines back out to sea.

To handle the April 2024 flood, operators said pumps ran for three to four days at maximum capacity, pushing out more water than the system had encountered since going online three years before. Workers are constructing a new pipeline to the ocean and more pumps are planned — the underground tunnels under construction will ultimately connect with the existing system.

“We want to actually push more water to the sea,” said Aliya Ibraheem Alhosani, a senior electrical engineer with the Dubai municipality. “We want the system to handle more flow.”

Back in Oman, authorities have been building a network of dams in the mountains to keep floodwaters from sweeping down the wadis. They are studying 14 major wadis that funnel to the al-Batinah coastline in preparation to build more dams to protect residents, said Jahwari, with Oman’s water agency. Across Oman, there are agreements to build 58 new dams. Billboards along the highways also announce that new flood evacuation centers are coming soon.

Residents often marvel at the pace of repair and recovery after a flood. The government rapidly rebuilds washed-out roads, bridges and culverts, and often pays for the entire cost of rebuilding destroyed homes.

But even if repair is quick, Rawas said Oman is still a long way from understanding this threat. Flood hazard maps remain rudimentary. People still build homes in wadis, where properties can be cheaper and easier to expand. He and his colleagues have spent years gathering detailed data about soil type, topography, the extent of the development footprint, the characteristics of desert storms — all to understand how flash floods behave in a single wadi.

His ultimate goal is an interactive flood map for the entire country. This could inform future development and also warn residents which roads should be closed, and which communities should be evacuated, to avert the type of tragedy that happened in Samad al-Shan.

“Right now we don’t have anything like that,” he said.

‘This one came all of a sudden’

The morning of the flood, the Azzan Bin Tamim School for Boys summoned bus driver Abdullah Said al-Rashdi to pick up students. The rains had started and school was closing. He loaded 25 teenagers into his beige Mitsubishi and set off through the wadi.

He had driven about three miles through pouring rain and flooded streets when the engine died. Instead of trying to restart the bus and drive to safety, he told the students to run to high ground. A few minutes after they escaped, a surge of roiling brown water washed over the windshield and swept the bus away.

“This one came all of a sudden,” Rashdi recalled.

Others caught in the wadi weren’t so lucky.

At the al-Hawari school two miles away, students had not been sent home, even as some worried parents raced to the school to pick up their kids. One family member loaded about a dozen middle school boys into his white SUV, but the vehicle got stuck crossing the swiftly moving water.

The uncle who was driving managed to escape. Ten of the children, all from the same extended family, died in the flood.

The tragedy remains an open wound in Samad al-Shan. The boys’ parents have a dispute with government officials for keeping school open that morning, according to a relative of the boys who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid retribution. A lawyer for the family recommended they not speak publicly, he said.

“Everyone’s afraid,” he said.

At least two days before the flood, Oman’s early-warning center had announced that heavy rains were expected and activated its emergency committees, including in the governorate that included Samad al-Shan, but several residents said the warnings did not seem particularly urgent.

Col. Zayid Hamed al-Junaibi, head of Oman’s national emergency management center, said the country’s emergency protocols had been followed during this storm, and authorities saved many lives. He said the Royal Oman Police generally set up checkpoints at wadi crossings to keep people back, “but unfortunately it’s not possible at every area where people might cross.”

“The rains were very heavy,” he said.

Since the flood, Oman has decided to relocate several schools from flood-prone areas, and students now practice evacuations, he said.

On that April day, the two sheikhs could not escape in time. Naser, a heavier man who had heart trouble, couldn’t free himself from his car, his relatives said, and Saif refused to leave his best friend behind.

Perhaps Saif could have saved himself, his son said, “but he’d never have forgiven himself.”

They are now buried side by side, their graves marked by matching marble headstones.

Niko Kommenda contributed to this report.

About this story

Topper video by AP.

Design and development by Talia Trackim. Editing by Paulina Firozi, Dominique Hildebrand, John Farrell, Betty Chavarria and Gaby Morera Di Núbila.

Methodology

To investigate global changes in extreme precipitation, The Post measured the amount of water vapor flowing through Earth’s atmosphere, a metric called integrated vapor transport (IVT). The analysis also identified days and locations where heavy rainfall coincided with high IVT. See more about The Post’s methodology for the IVT analysis here.