After a summer lull in the United States in avian influenza cases among poultry and dairy cattle (and no human infections reported in the country since February), the virus has returned.

Bird fluThe return of the US threatens major economic losses for the US agricultural system and causes small but real risk of a human pandemic. Scientists expected the return of bird flu. It is unlikely that after three full years of infesting poultry in the United States and creating amazing cow jumpthe virus will simply disappear.

The currently circulating avian influenza subtype H5N1 is here to stay. “We have come to terms with this phase,” says Seema Lakdawala, a virologist at Emory University. “Now we need to decide what to do next.”

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientific American spoke with Lakdawala and other experts about why the virus is back, what threats it poses and what people need to know.

How common is bird flu now?

Avian influenza is on the rise in poultry, with 50 commercial and backyard poultry flocks in the country confirmed to be infected with avian influenza in October, according to the USDA. Farmers kill all birds in infected areas to reduce the spread of the virus.and more than three million animals have been killed so far this month.

Carol Cardona, an poultry veterinarian at the University of Minnesota, said she's concerned that the state's animal health board has already reported 20 flocks with confirmed infections since early September. “We're definitely having a bad year here in Minnesota,” Cardona said.

An outbreak in dairy cattle, identified in March 2024, is also ongoing. The virus is more difficult to trace in cattle because, unlike poultry, the animals generally do not die after becoming infected. However, infection reduces cow productivity.

Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and a senior veterinarian at the University of Wisconsin, notes that several states, including California and Idaho, are seeing ongoing cases of infection in cattle, but he knows about this only from informal conversations with colleagues. Meanwhile, last month the USDA confirmed the first known dairy infection in Nebraska, suggesting the virus is still spreading among herds. But in general, the registration of cases of infection in dairy cattle is slow and unorganized. “We don't have enough information to know what our risk is, and it's a pretty precarious position,” Poulsen says. “We don't know what we don't know.”

Why is bird flu on the rise again?

The nationwide number of poultry infections this month has risen sharply compared to the summer months, with fewer than one million poultry culled in June, July and August to combat avian influenza. But scientists expected there would be an increase in the prevalence of the disease among poultry as autumn approached for two reasons. First, warmer temperatures seem to suppress the virus and the weather is getting cooler. “The virus survives better in cold weather,” says Rocio Crespo, an avian veterinarian at North Carolina State University. “So we will have more outbreaks than we saw in the summer.” Secondly, bird flu widespread among wild birdsand many of these birds migrate south to warmer climates, carrying the virus with them.

Together, these two factors mean that avian influenza cases in poultry have acquired a visible annual cycle since the current outbreak was first identified in early 2022, with losses typically lowest in June, July and August and highest in December, January, February and March.

How does the government shutdown affect the fight against bird flu?

The federal government has been shut down since Oct. 1, when the new fiscal year began without any measures to fund routine operations. Across the government, only those employees deemed “critical” by federal agencies continue to work.

Spokesmen for the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, which maintains the agency's avian influenza dashboards, did not respond to Scientific Americanrequests for detailed information about office staffing during closures. Cardona says she knows agency staff in Minnesota and surrounding states are continuing to work on avian influenza, with case dashboards for poultry, dairy and wild birds showing updates dating back to October.

Much of the U.S. response to avian flu has always been at the state level rather than the federal government, Poulsen said, meaning surveillance and control plans are still being implemented. “Surveillance works,” he says. “We find the positives and deal with them accordingly.”

Poulsen said he now sees a key weakness in interstate communication, which the USDA facilitated through meetings that have now been cancelled. He also says the agency does not have enough veterinarians and support staff to face the reality of the current animal disease situation in North America, which includes not only avian influenza but also New World Worm infestations, foot and mouth disease and African swine fever.

How is avian influenza related to seasonal influenza in humans?

The seasonal increase in avian influenza incidence among poultry coincides with the start of the human influenza season, raising concerns among scientists that these flu viruses can mixwith potentially devastating consequences.

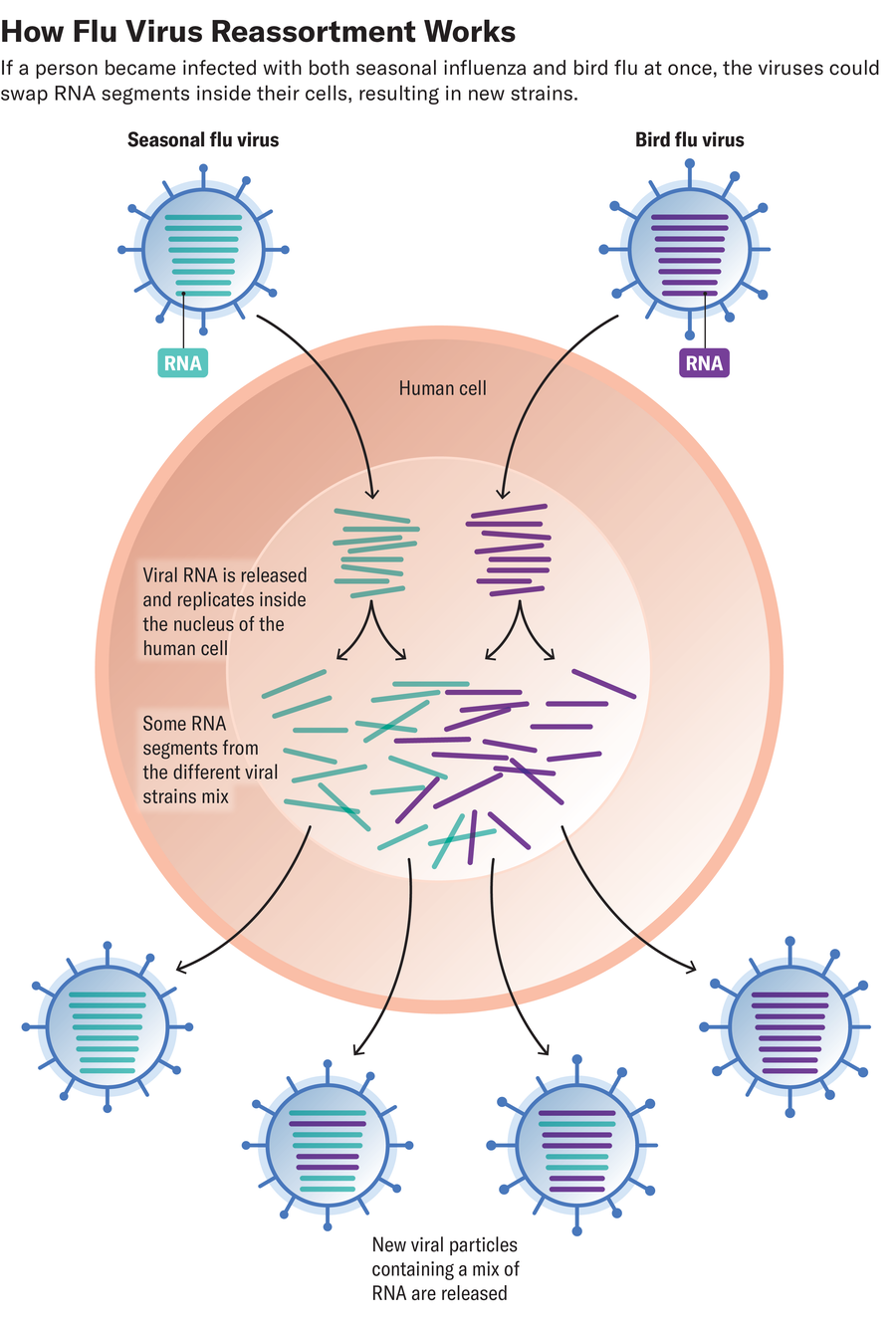

Influenza viruses tend to exchange genetic material with each other, a process called reassortment. This is one of the main reasons that every year Scientists are developing a new flu vaccine to target the specific strains they expect to spread the most. If the bird flu virus gains the ability of seasonal flu to easily infect people, the result could be a new pandemic disease to which people have no existing immunity and which scientists fear will have an even higher mortality rate than COVID did during its initial emergence.

The cow's udder can become one of the places for the development of such a hybrid virus.. But scientists are also concerned about co-infection in humans—cases in which the same person becomes infected with both avian influenza and the seasonal influenza virus.

Fortunately, it would likely take many such coinfections in humans for a dangerous virus to emerge, since influenza reassortment in humans is relatively rare, Lakdawala says. “Two viruses have to get into one cell in your body, out of millions, billions of cells, multiply and create something new,” she says. Unfortunately, the more common each virus is, the greater the likelihood of such coinfections, making the corresponding rise in avian influenza and seasonal human influenza dangerous.

How dangerous is bird flu?

The risk to most people from the current strain of bird flu is quite low, experts say. Although the CDC has reported 70 confirmed cases in humans, nearly everyone infected has had direct contact with infected animals. most cases were mild. This contrasts with previous outbreaks of other avian influenza strains, which are estimated to killed up to half of infected people.

For now, Poulsen is much more concerned about how the nation's poultry and dairy farming systems will cope with a virus that continues to infect the animals on which those industries depend. For example, he is afraid another jump in egg prices this will be similar to what was observed in the US in late 2024 and early 2025. An economic landscape that is currently being shaped by higher prices caused by tariffs..

“The public will see more expensive food or may not be able to get it,” Poulsen says.

How can people protect themselves from bird flu?

Although avian influenza does not currently pose a high risk to most people, experts still recommend several steps to protect yourself and others from the virus:

People who regularly come into contact with animals susceptible to avian influenza should be more careful. If you keep poultryBe aware of the prevalence of bird flu in your area and handle birds only with personal protective equipment (masks and gloves) and clothing that is left outside the home. Farm workers must also wear protective gear and follow biosafety protocols, although scientists understand that these workers need better tools to ensure their safety. “We have excellent personal protective equipment for people working in laboratories,” Crespo says. “But a lot of them don’t do very well on the farm.” She's excited recent workshop held by the National Academy of Sciences to bridge this gap.

What are the most important questions about avian influenza right now?

This year, Cardona is particularly interested in how the virus will evolve. She sees evidence that avian influenza in wild birds is undergoing significant changes. Influenza is identified by two surface proteins. The avian influenza virus currently circulating is a subtype called H5N1. But Cardona says she is now hearing about cases of the H5N2 subtype, as well as cases of H5N1 with a different gene makeup. “The virus camouflages itself,” she says. “This may change the behavior of the virus in animals.”

Crespo focuses on the experiences of poultry farmers who desperately want to know how the virus is getting into their flocks, despite having implemented a range of measures aimed at protecting the birds.

And Poulsen wonders how the Trump administration's work to shrink the federal government and attack science will affect the U.S. response to avian flu—and our public health system overall.

But as concerned as these experts are about the return of bird flu and the problems it poses, they are still fighting. “One of the advantages we have over this virus is that we are smarter than it is,” Cardona says. “We really need to start using the brain and figuring out how to get into a more manageable state.”