Rachel Hagan And

Mark Poynting,Climate reporter

A very powerful hurricane hit Jamaica, becoming the strongest storm to hit the Caribbean island in modern history.

Hurricane Melissa, now a Category 4 hurricane, first hit the island's south coast with maximum sustained winds of 295 km/h (185 mph), the strongest on Earth this year.

These speeds are higher than those of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, one of the most powerful storms in US history.

For a country already on the front lines of the fight against climate change, the threat is serious.

So why is this particular hurricane so dangerous?

How Melissa became a Category 5 monster

Tropical Storm Melissa took shape last Tuesday and then quickly intensified as it moved west across the Caribbean Sea.

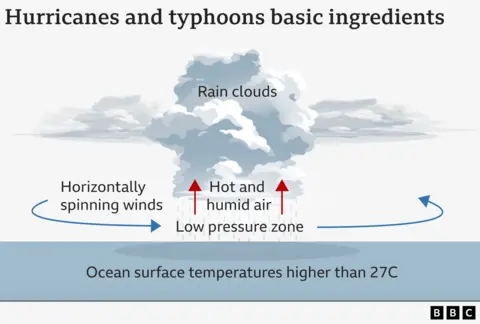

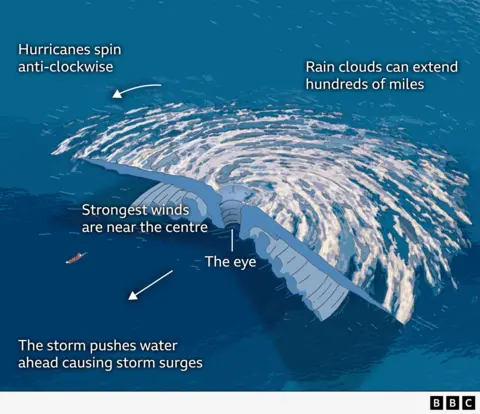

A hurricane forms when warm, moist air rises from the surface of the ocean and creates a rotating system of clouds and storms. In the center, the air sinks to form the eye, a calm, cloudless area surrounded by a wall of strong winds and rain known as the eye wall.

Melissa's origins can be traced to a cluster of thunderstorms off the coast of West Africa in mid-October. By October 21, it had reached tropical storm strength, and by October 26, it was a Category 4 beast sweeping across the Caribbean.

Ocean temperatures in the Caribbean are unusually high this year, and hurricanes are feeding off this warm layer of water. These conditions allowed Melissa to become active quickly.

“The ocean is warmer and the atmosphere is warmer and wetter due to [climate change]” says Brian McNoldy, senior research scientist at the University of Miami.

“So this tips the scales in favor of things like rapid intensification [where wind speeds increase very quickly]higher peak intensity and increased precipitation.”

Low pressure and strong winds

Melissa is considered one of the most powerful storms to hit the Atlantic this century.

For Jamaicans, comparisons to past storms are daunting. If it hits Jamaica at near full force, it could dwarf any storms the island has experienced before. Gilbert in 1988, the last direct hit, was a Category 3. It destroyed thousands of homes and killed 49 people. Dean in 2007 and Beryl in 2024 came close, but neither could match Melissa's strength.

The storm's central air pressure fell to 892 millibars, which is 902 mb lower than Hurricane Katrina's pressure by 902 mb, according to the National Hurricane Center on Tuesday morning local time. The lower the pressure, the stronger the winds, making this one of the most powerful systems ever to form in the Atlantic.

Hurricane Katrina, which struck New Orleans in 2005, killed 1,392 people and caused damage estimated at $125 billion (£94 billion).

“This will be the strongest hurricane that has ever hit [Jamaica]At least in the records we have,” Dr Fred Thomas, a research software engineer at the University of Oxford's Institute for Environmental Change, told the BBC.

The storm caused the death of four people in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Jamaica's health minister said Monday that three people have died on the island as it prepares for the approaching storm.

Melissa strengthened particularly quickly, helped by very warm waters in the Caribbean, about one to two degrees above average.

“There was a perfect storm of conditions that led to the colossal intensity of Hurricane Melissa,” said Dr Lynne Archer, a research fellow in climate extremes at the University of Bristol.

Slow pace creates risk of catastrophic flooding

Although the wind speed is staggeringly high, the storm's movement is noticeably slow. Melissa herself was crawling west Tuesday at a speed of about 5 km/h – slower than a person's walking speed.

Meteorologists warn that this lethargy could have disastrous consequences as the storm could bring rain in one place for days on end, worsening flooding.

When hurricanes pass, they linger in one area much longer than usual, leading to repeated waves of rain, flooding and wind damage.

One of the most famous examples of this is Hurricane Harvey in 2017, which stalled over Houston in the US. Harvey released 100 cm of rain in just three days, causing catastrophic flooding.

The US National Hurricane Center warned that Jamaica could receive between 38 and 76 cm of rain, with up to a meter in some mountainous areas.

Storm surges of up to four meters are possible, especially along the southern and eastern coasts of the island. Low-lying parishes such as Clarendon and St Catherine are at risk of flash flooding, not only from rainfall but also from runoff from the Blue Mountains.

“Imagine a meter of rainfall falling across the entire basin and then being released into the river network. By the time they reach the lower parts of this drainage network, it will be meters and meters of flooding. So I believe the flooding is likely to result in a large loss of life,” said Dr Thomas, who visited Jamaica earlier this year.

Reuters

ReutersSome studies show that hurricanes tend to move slower than before. This means more storms like Melissa may stick around rather than rush past the land they hit.

Some scientists believe this may be related to the way climate change is affecting circulation patterns in our atmosphere, but this is far from certain and natural variability may also play a role.

Jamaica 'unprepared'

Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness has already warned that “no infrastructure can withstand Category 5.”

Dr. Thomas largely agreed, but explained that most new buildings in Jamaica are constructed of reinforced concrete, as required by national building codes.

“Anything built to these rules should be pretty strong in terms of wind, but wind only has one effect,” he said.

“The worst thing about Melissa is not just the wind, it’s the rain and storm surge. You could completely flood the entire first floor and then part of the first floor.”

In larger cities such as Kingston and Montego Bay, the construction is more robust, he said, but in rural areas and hillsides, “there's more vernacular architecture.” [some things built from wood] rather than larger concrete type buildings.” Things are much worse with them.

“This hurricane will be very difficult for Jamaica,” says Kerry Emanuel, professor emeritus of atmospheric sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Jamaica is “not prepared to effectively cope” with severe storms, Dr Patricia Green, an architect and conservationist from Kingston, told the BBC. She recalled how “a couple of hours of rain” in September caused “massive flooding” in the capital, exposing deep flaws in urban planning.

She criticized the rise of high-rise developments “located in areas that are supposed to be the city's drain,” saying they have caused flooding in areas “that have never experienced flooding before.”

As a low-lying island nation, it is particularly prone to storms. According to the Government of Jamaica, about 70% of the population lives in coastal areas.

And as with extreme weather, poor communities are expected to be hit hardest.

“It's one of those worst-case scenarios that you prepare for but desperately hope never happens,” says Hannah Cloke, professor of hydrology at the University of Reading.

“The entire country will be deeply and indelibly scarred by this terrible storm. It will be a long and grueling recovery for those affected.”

Tourism is another problem. Jamaica's major resorts are mostly built of concrete, but their strength has never been tested by winds of such strength.

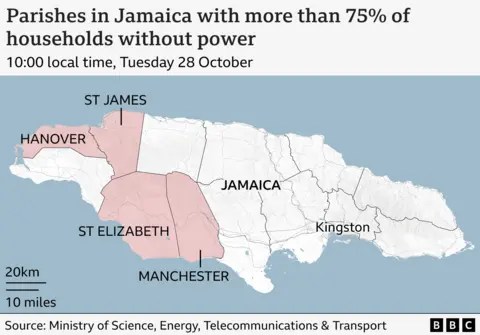

Other parts of the country's infrastructure are more vulnerable and power is expected to go out. Dr Thomas said: “The network is likely to be down in some areas ahead of the worst of the storm. But then there are poles and lines brought down by debris and trees. Often it’s not the wind itself, but what the wind catches.”

In addition to buildings, the storm threatens Jamaica's power, water and transportation networks. Falling trees and flying debris are expected to damage power lines. Flooding can cause sewer systems to fail and contaminate water supplies. Landslides are likely to cut off mountain roads, isolating rural communities.

Dr Green said current architectural trends were degrading sustainability, and the move from traditional slat shutter windows to fixed glass could leave buildings more vulnerable. Sealed glass prevents air from passing through, increasing pressure inside and making walls and roofs more likely to fall during a storm.

Most vulnerable, she added, are poorer communities, especially those living along riverbanks and ravines, which Dr Green said is a “historic, colonial problem” dating back to emancipation, when previously enslaved people were given marginal land. Many of these families have lived there for generations without affordable alternatives or secure land rights, she said.

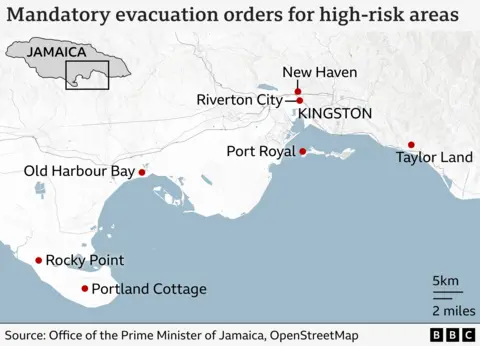

Dr. Thomas highlighted Port Royal, a small fishing village in Kingston that is considered one of the most vulnerable communities to hurricanes and is on the mandatory evacuation list.

He visited in February, explaining: “It's sort of a long strip of land, and it's extremely open, seven or eight miles from the mainland, so it can be cut off quite easily.”

The ripple effects of any single failure can be widespread: “The power goes out, and then the telecommunications go out. Hospitals have backup for a while, but often not long enough. And the airport is closed, which means help cannot be delivered quickly.”

With airports closed, supply chains disrupted and aid flights grounded, even after the storm passes, recovery could take months.