Adrienne Murray and James BrooksTechnology reporters

Beta Technologies

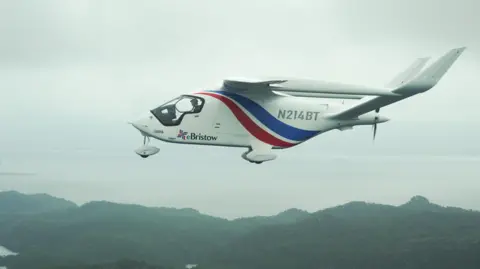

Beta TechnologiesAn aviation rarity landed in Norway's second city of Bergen earlier this month.

Aaliyah flew 100 miles (160 km) in 55 minutes using only the battery.

The electric aircraft, built by American aerospace company Beta Technologies, is designed for cargo operations carrying loads weighing up to 560 kg (half a ton).

The flight simulated a planned cargo route between the coastal cities of Stavanger and Bergen, and test flights will take place over the next few months as part of the country's efforts to create low-emission aviation.

At the helm was pilot Jeremy Degagne: “If you drive, it’s four and a half hours. And we made the flight in 52 minutes.”

“This is an important milestone for Norway as an international testing arena,” says Kariann Helland Strand, director of Norwegian airport operator Avinor.

The test flights in Norway follow a whirlwind European tour that began in Ireland and saw Aaliyah debut at the Farnborough and Paris air shows, as well as stops in Germany and Denmark.

Beta Technologies

Beta TechnologiesThe Alia can fly up to 400 km (250 miles) on a single charge and refuel in less than 40 minutes when plugged in like an electric car.

The same fixed-wing model can be configured for medical transport or passenger transport with up to five seats. In June of this year, it made its first electric demonstration flight, carrying passengers to New York's John F. Kennedy Airport.

Beta, which counts Amazon as an investor and UPS as a customer, hopes to get its plane certified in the U.S. this year.

“I believe the next big thing in aerospace will come from electric propulsion,” says Beta Chief Revenue Officer Sean Hall, a former fighter pilot.

“We can now significantly reduce operating costs, and this is good for the environment in terms of carbon emissions.”

Alia is one of the most advanced projects among dozens of firms exploring electric propulsion systems in aviation.

This would be one way to reduce the carbon footprint of the aviation industry, which currently accounts for 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

However, the Pipistrel Velis Electro remains the only electric aircraft to receive full certification from European authorities. despite overcoming this obstacle five years ago.

With a range of 185 km and a flight time of 50 minutes, the Slovenian-built Pipistrel is intended solely for training purposes and not for transporting passengers from point A to point B.

But such successes were overshadowed series of failures in electric aviation.

Even aviation giant Airbus has left the market. In January, the company announced the development of its electric aircraft, CityAirbus. will be postponed.

Airbus

AirbusFlight range remains the main limitation of electric flight. Even the best lithium-ion batteries are bulky and heavy, and have an energy density far lower than jet fuel.

They have “not improved significantly” over the past two decades, says Guy Gratton, an aviation expert and professor at Cranfield University.

For electric flight to take off, he says, a “revolution” in battery chemistry is needed.

Given these limitations, some are considering alternative technologies.

Just as hybrid cars were a stepping stone to electric cars; Aircraft manufacturers are also now experimenting with hybrid technologies.

Among the aviation startups trying to launch electric passenger planes is Heart Aerospace.

The company recently moved all of its operations from Sweden to the United States, a move executives say will help it concentrate “resources” and get closer to customers including airlines Mesa and United.

The firm developed a 30-seat prototype of the X1 aircraft, which the BBC saw before being sent to the United States.

If all goes according to plan during upcoming test flights, it will become the largest battery-powered aircraft to ever fly. “It has about two tons of batteries,” explained technical director Benjamin Stabler.

The heart of the aerospace industry

The heart of the aerospace industryFor its actual operations, however, Heart uses a fundamentally different design: a hybrid aircraft that runs on batteries but carries spare fuel.

“You don't need it because [many] batteries,” Mr. Stabler says, making it lighter and cheaper and allowing it to carry more paying passengers.

“For a conventional route, it will fly entirely on electric power from takeoff to landing,” he explained.

“If you want to go longer distances or there is a deviation, you can switch to turbines.”

The plane could fly 200 km on electric power alone. Thanks to hybrid technology, test flights of which are scheduled for 2026, the company claims it will be able to fly 400 km with 30 passengers or up to 800 km with 25 passengers.

“Flying on public transport rightfully requires a significant amount of energy,” says Professor Grattan.

“So hybridization and the use of traditional fuels to create safety margins makes sense,” adds the professor, who has previously advocated this approach.

The heart is not alone in this area.

US aerospace startup Electra expects its nine-seat hybrid aircraft to fly by 2029 and run on a combination of jet fuel and electric power.

Beta Technologies also develops hybrid aircraft for defense and civil purposes. Its first model was built in 2023, and later this year the company plans to release an aircraft that is not only hybrid, but also autonomous.

“Are we excited about the hybrid? 100%,” says Mr Hall.

“Today it’s a way to extend your flight range, and you still get significant environmental benefits.”

First you need an all-electric base, Mr. Hall argues, “then you layer on the hybrid technology.”

Hybrid systems have lower emissions than conventional aircraft, and electric motors will provide quieter takeoffs and landings in urban areas.

It is still unclear what the future of aviation will look like.

Cleaner fuels such as clean aviation fuel (SAF), along with hydrogen-based systems, have attracted investment.

All will have to prove their commercial viability and safety, and there is a lot of work to be done.

“It's a really big challenge to electrify aviation and remove carbon emissions,” Mr. Stabler said.