Helen BriggsEnvironment Correspondent

Getty

GettyA volcanic eruption around 1345 may have set off a chain reaction that triggered Europe's deadliest pandemic, the Black Death, scientists say.

Clues preserved in tree rings suggest the eruption triggered a climate shock and led to a chain of events that brought disease to medieval Europe.

In this scenario, ash and gases from a volcanic eruption caused temperatures to plummet and led to poor harvests.

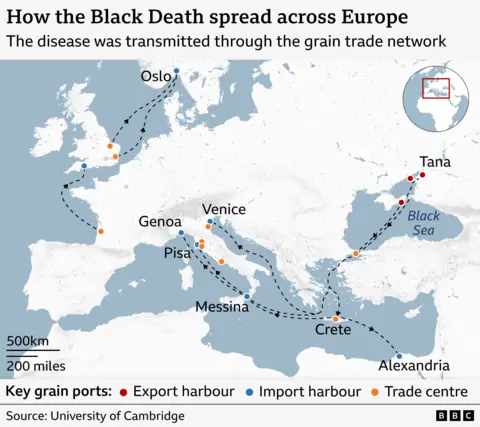

To prevent famine, the populous Italian city-states were forced to import grain from areas around the Black Sea, bringing with them the plague-carrying fleas that also carried the disease to Europe.

This “perfect storm” of climate shock, famine and trade serves as a reminder of how diseases can emerge and spread in a globalized and warmer world, experts say.

“Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death appears to be rare, the likelihood of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and becoming pandemics is likely to increase in a globalized world,” said Dr Ulf Büntgen from the University of Cambridge.

He added: “This is particularly relevant given our recent experience with Covid-19.”

Credit: Ulf Büntgen

Credit: Ulf BüntgenThe Black Death swept across Europe in 1348–1349, killing up to half the population.

The disease was caused by a bacterium known as Yersinia pestis spread by wild rodents such as rats and fleas.

The outbreak is believed to have started in Central Asia and spread worldwide through trade.

But the exact sequence of events that brought the disease to Europe and killed millions of people is being carefully studied by scientists.

Now researchers from the University of Cambridge and the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) in Leipzig have filled in the missing piece of the puzzle.

They used tree rings and ice cores to study climate conditions during the Black Death.

Their findings suggest that volcanic activity around 1345 led to a sharp drop in temperatures in subsequent years due to the release of volcanic ash and gases that blocked some sunlight.

This, in turn, led to crop failures throughout the Mediterranean region. To avoid famine, Italian city-states traded with grain producers around the Black Sea, unwittingly allowing the deadly bacterium to gain a foothold in Europe.

Getty

GettyDr Martin Bauch, a historian of medieval climate and epidemiology at the GWZO, said climate events collided with a “complex food security system” in what could be described as a “perfect storm”.

“For more than a century, these powerful Italian city-states established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and Black Seas, allowing them to activate a highly effective famine prevention system,” he said. “But it will inadvertently lead to a much greater disaster in the long run.”

The results are reported in the journal. Connection Earth and environment.