One afternoon in October, almost four years into Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, I was sitting in the sleek, modern offices of PEN Ukraine in Kyiv. We had gathered for a week-long series of meetings with writers, journalists, and human rights activists, and to visit scenes of Russian crimes in liberated areas around the country. Wartime realities made themselves apparent from one of our first sessions, in which delegates were to give brief presentations introducing ourselves and our work. Just as I was called upon to speak, our phones lit up with alerts.

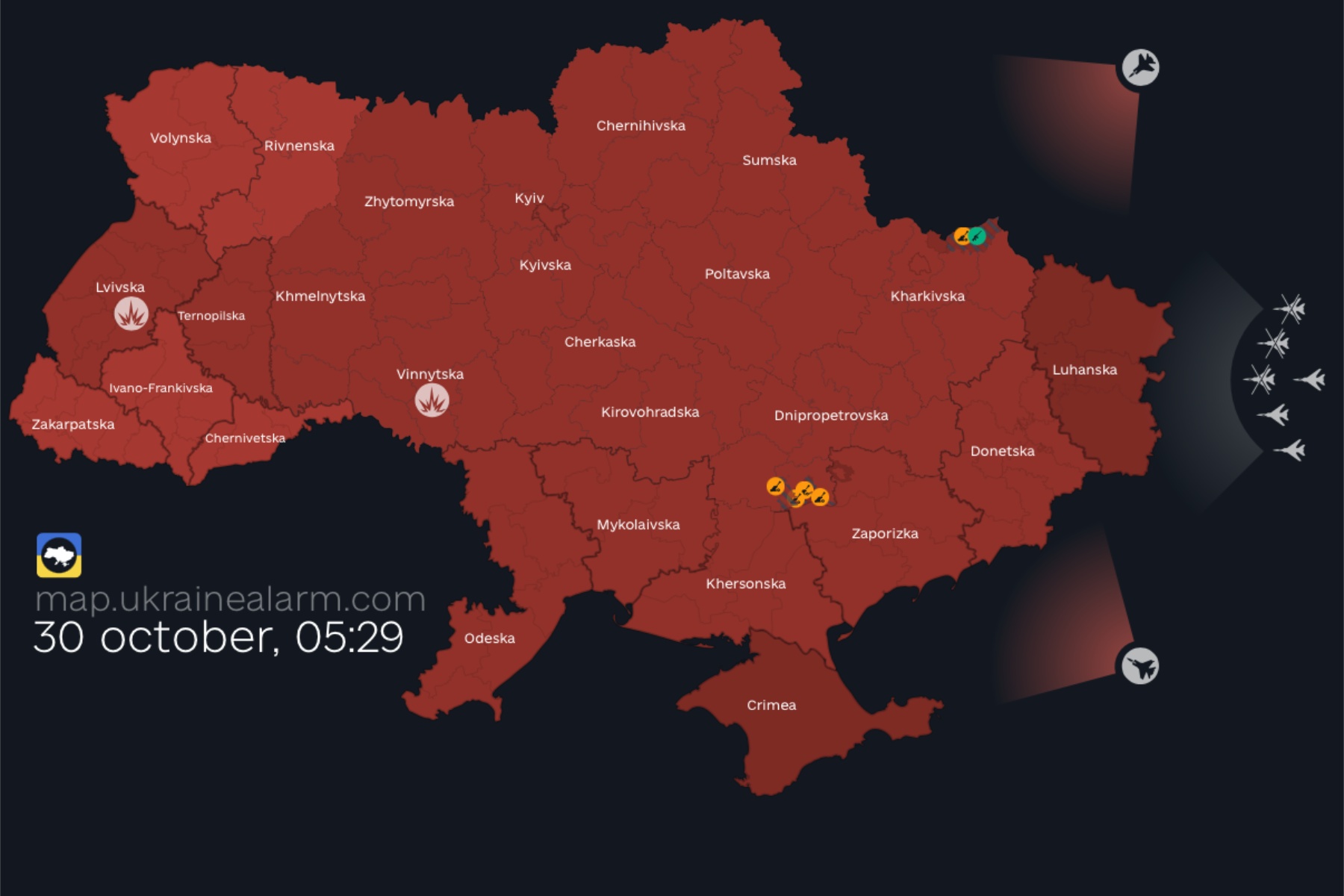

“Attention!” they blared. “Air raid alert. Proceed to the nearest shelter.” Maksym Sytnikov, the executive director of PEN Ukraine, gave the group a weary smile. We picked up folding chairs and headed for the elevator. I continued my presentation in the underground parking garage. Perhaps a half hour later, the phones lit up again. “Attention! The air alert is over. May the force be with you.” (The English version of the Air Alert app is voiced by Mark Hamill, a.k.a. Luke Skywalker.)

Missile and drone attacks were, by now, part of the background of life in Kyiv. Since failing to capture the Ukrainian capital in the early days of its full-scale invasion in 2022, Russia had, according to one independent monitor, pounded Kyiv more than 199 times as of December 18. It had used ballistic and hypersonic missiles and ever more sophisticated drones—including the turbojet-powered Geran-3, which can approach targets at speeds of up to 370 kilometres per hour, exploding on impact.

The effects of this campaign were visible everywhere: driving around the city, we saw buildings with their windows blown out, with missing walls and roofs. An office complex near our hotel in Podil had been hit by a missile on October 23, four days before we arrived.

Most of these strikes occurred around 4 or 5 a.m., on the theory that attacking a population in the deepest phase of sleep will deliver maximal shock. While a majority of Russian strikes now targeted energy infrastructure—the Kremlin hoped to weaken Ukrainian resolve by depriving them of heat and electricity over winter—some drone and missile attacks were meant to feel perfectly random. “They want you to feel as though you can die at any place, and any time,” said Sytnikov. “It’s Russian roulette.”

Another short drive and we were on Václav Havel Boulevard, facing a nine-storey residential building—the middle section of which had been obliterated last June by a Russian cruise missile that killed at least 28 and injured 134. On the dreary morning we visited, the site was totally unsecured, without even perfunctory police tape to prevent people from wandering through the rubble.

I walked around back and noticed a playground not fifty metres from the collapsed building, as well as a small collection of stuffed animals placed at the base of the wreckage. Oleksandr Ustenko, a former resident of the building, remembered the sound of the missile. “At some point, everything started shaking,” he told reporters the morning after the attack. “The ceiling shook, and the door was blown out.” Everything was on fire.

I looked up, and crumbled walls revealed the interior of a third-floor apartment: floral wallpaper, an overturned mattress, a woman’s handbags still hanging from their hooks. “We realize now that our privacy is very fragile,” said Anna Vovchenko, a translator and project manager at PEN Ukraine, as she surveyed the exposed apartments. We think of our private lives as sealed off from the public world, but war reveals the provisional nature of those walls, and of the privacy they promise.

When our hosts dropped us off for the evening, they warned us of ominous chatter on Telegram. We might be in for a bad night. I laid out my clothes on a hotel chair, hoping these meagre preparations might somehow ward off the worst. The Air Alert sounded at 12:30 a.m. For the next few hours, those of us in the shelter (which was more of an underground office) tried to read, or work, or scroll. Then we tried to sleep—without success, in my case. During these hours of exhaustion and boredom, I found I needed to scare myself to resist the temptation of my bed. Go back to bed and you’ll get blown to pieces, I told myself. People die in these attacks all the time—why not you? What makes you think you’re special?

This was, of course, exactly what our Russian tormentors wanted us to think. Terror was the point. Which was why, these days, most of the Ukrainians I spoke with no longer gave Putin the power to dictate when they sleep. They remained in their homes, and let the devil do his worst. It was 7:15 the next morning when the Air Alert finally ended, and Mark Hamill offered his surreal benediction: “May the force be with you.”

The next day, our group travelled to the village of Yahidne, about two hours northeast of Kyiv. There, we met Ivan Polhui, a retired kindergarten manager in his early sixties. Polhui, who wore a grey moustache and formless Ford baseball cap, told us about the ghastly events he and other villagers endured in 2022. After failing to capture the city of Chernihiv, he explained, Russian soldiers retreated to nearby villages for a ready supply of human shields. That March, they rounded up the more than 300 residents of Yahidne—ranging in age from ninety-one to under two months—and imprisoned them in the basement of the local school.

Polhui led us down a steep stairway into the bowels of the school, where, for nearly one month, his entire village was imprisoned. What hit me first was the dank, mildewed odour; there was little ventilation down there, and the prisoners soon found it difficult to breathe. Polhui recalled that the basement was so crowded that their breath condensed on the ceiling and dripped back down in a sickly rain. They rigged up some cardboard to keep it off the children.

As he led us down the narrow hallway, Polhui pointed out numbers scrawled on door frames, indicating how many people were forced to live in each room: one of them, perhaps two by four metres, the size of a typical bathroom, contained nineteen adults and nine children. I tried to imagine sharing this modest space with twenty-seven other people, for hours and days on end. Some walls were decorated with drawings of cats, trees, elephants, and other creative traces of children—for whom the hours upon hours of captivity must have been particularly agonizing.

In these conditions of intense overcrowding, routine bodily functions became occasions of unforgettable shame. Buckets served for toilets; permission to empty them was often refused. Food ran out within a week. Eventually, they were permitted a few potatoes or cabbages, which were boiled in water; Polhui recalled that they were each allocated half a cup of this liquid, which often served as their only nutrition for days. Breastfeeding soon became impossible for the mother of the infant. When she asked if she could step outside for some oxygen, one of her captors replied: “If the baby dies, let it die. There will be one less of you here.”

Sickness was rampant, including an outbreak of chicken pox that tore through the captives. No medicine was provided: if someone found a painkiller, they’d divide it among the children to make their suffering more bearable. Soon enough, these inhumane conditions took their fatal toll, and people began to die. Some lost their minds first, Polhui recalled, screaming and beating their fellow captives with chairs. Survivors were forced to live among the corpses. Polhui was haunted by memories of children sleeping next to dead bodies.

As time wore on, the line between the living and the dead began to blur. Polhui recalled how one woman, presumed dead, was piled with a heap of corpses. The next day, she woke up. “We were exhausted to an extent that you can’t even imagine,” he said.

Eventually, they were given half an hour to bury their dead. But another group of soldiers hadn’t got the message and began shooting at them. The villagers dived into freshly dug graves for cover. By the time they scrambled back to their basement prison, they had sustained cuts and broken bones.

One day, Polhui recalled, their captors reverted to crude psychological tactics. They switched on a light and started reading Russian propaganda newspapers. Kyiv had been seized, they announced, Zelensky had fled. There was no option but to become Russian citizens. They were forced to sing the Russian national anthem—“but nobody believed any of it,” Polhui said. Even in their extreme deprivation, the villagers saw through the Russian mind games: their captors were only there because they had failed to capture Chernihiv. They weren’t moving on because they couldn’t. On a wall, someone wrote the lyrics of the Ukrainian national anthem.

After nearly a month of unimaginable torment, Ukrainian forces arrived to liberate the villagers. No sooner had they emerged from their subterranean prison, however, than they saw the state of their homes, which had been occupied by Russian soldiers. “They had shit everywhere,” Polhui recalled—in the kitchens, in the bedrooms. They’d stolen what they could, and destroyed what they couldn’t. (Elsewhere, Russian soldiers had made off with TVs, washing machines, even toilet bowls.) Seeing the state of their homes, many left Yahidne. But others had nowhere else to go. They went back to the school.

I had been in that basement for no more than an hour but was relieved to ascend into the fresh air. Someone in our group asked Polhui if it was helpful or painful to share this experience. He paused, eyes glassy. “It is very difficult to remember the children in that basement, to remember my own grandchildren in that basement, all over again,” he said. “It is a very painful experience to recall. It is awful to be undressed in the eyes of your children. To have soldiers shoot over your head, shoot beneath your feet. To play with you like a living target.”

Eleven villagers died in that school basement, according to Polhui; other reports list twenty dead. There was no official death count. The survivors, forever changed, now celebrate March 30—the day they were freed—as their second, shared birthday. Government grants allowed them to start rebuilding their homes, and the school was on its way to becoming a museum. “The point is to reveal what the Russians would do to the whole of Ukraine,” Polhui said, “and to reveal the truth of Russian culture.”

It sounds flippant to say that Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine is about “more than just territory.” As I write this, Ukrainian defenders are sacrificing their lives in Pokrovsk and Zaporizhzhia to defend every last inch of Ukrainian soil. Yet it’s also true that this war is about non-territorial questions of culture, language, and national identity. In an infamous 2021 article, Putin argued that Ukraine was not a real country—that “Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians are all descendants of Ancient Rus,” that “Ukrainization was often imposed on those who did not see themselves as Ukrainians,” and that “true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia.”

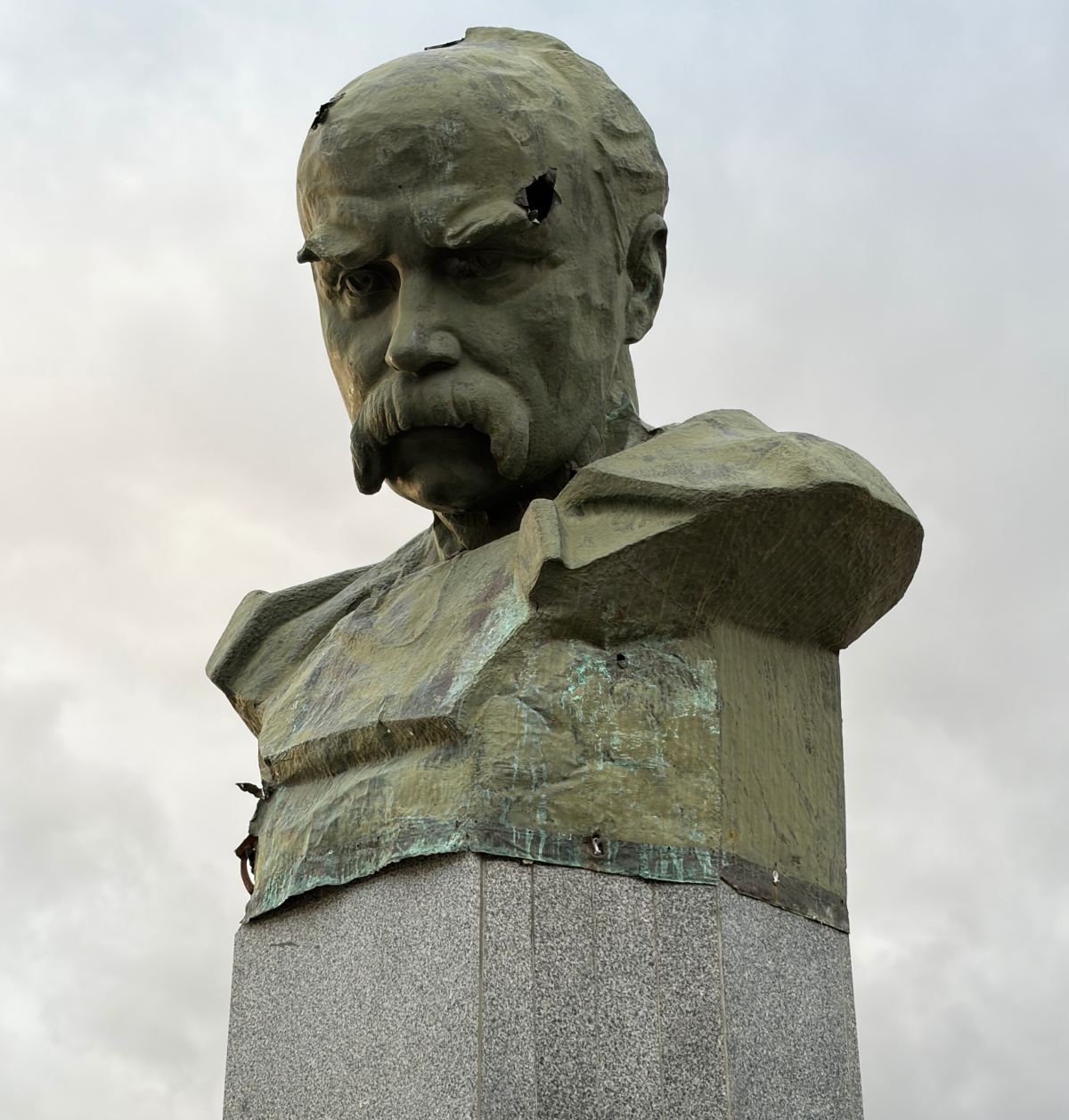

Nowhere are the dynamics of that “partnership” more obvious than in the town square of Borodianka, northwest of Kyiv, where Russian soldiers damaged and shot a monument to nineteenth-century poet Taras Shevchenko, who violated prohibitions against writing in the Ukrainian language and is now considered an important founder of modern Ukrainian literature. Ukrainian soldiers liberated Borodianka in 2022, and the Shevchenko monument—complete with bullet hole in its forehead—remains in the centre of the city.

In the early days of the war, Ukrainians—who recognized that Putin’s “partnership” would amount to cultural erasure—returned to Ukrainian art and literature with renewed interest. New literary festivals sprang up; sales of Ukrainian history books spiked. As the war stretched on, however, cultural workers were forced to confront existential questions. “What should culture do in these times?” asked Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta, director general of the Mystetskyi Arsenal, Ukraine’s flagship cultural organization. “Culture is often conflated with leisure and is therefore seen as demobilizing. But that’s not what we want. We cannot afford to be private people believing in pacifist ideals.”

Ostrovska-Liuta guided us through the cavernous exhibition spaces housed at the Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv. Dating back to 1783, during the reign of Russian empress Catherine II, the massive yellow-brick building long served as a Russian munitions factory. Today, the Arsenal is an important home for Ukrainian cultural expression, hosting multimedia exhibitions as well as Kyiv’s annual International Book Arsenal Festival (IBAF), the country’s premier literary event. But mounting such undertakings amidst the full-scale war has not been without challenges.

“There are obvious logistical issues with putting on a book festival when the electricity could cut out at any moment,” Ostrovska-Liuta told us. Last year, Russia began shelling electrical infrastructure one week before the festival opening. “We had to source new generators, and suddenly a large amount of our budget had gone to electricity,” she remembered. Then there were the air alert sirens, which Ukrainians preferred to ignore, but which sent international guests running for the shelters. International authors sometimes decline to attend the festival, “or say they will come—and cancel last minute,” Ostrovska-Liuta said.

Ukrainian writing has changed in recent years, as writers have rethought their commitment to long-form works, and reading demographics have shifted. Children’s literature, once the most successful arm of the Ukrainian publishing industry, has been in steady decline—a depressing reflection of the fact that there are ever-fewer children present in the country. (There are also fewer moms: as in Canada, women have historically accounted for a large portion of book sales in Ukraine.)

At the same time, interest in poetry—and especially in the performance of poetry—has been surging. Readings by Serhiy Zhadan attract as many as 4,000 attendees; poetry books are seen as supplementary to these live performances. These days, “the human voice is the protagonist of Ukrainian poetry,” said Vovchenko. The voice “reminds us that we are alive, we are feeling the presence of someone else who is alive, feeling the intimacy of someone speaking to you. This is why spoken-word poetry is so important.”

Ukrainian publishing is facing issues that are familiar around the world—paper is more expensive, readers are scarce—plus unique problems of publishing in a time of war. The nation’s largest printing facilities, in Kharkiv, are often under attack. Many publishing professionals quit to join the front lines, while others fled. These changes are no longer considered temporary, but structural. The industry will have to run on fewer human resources.

Still, new publishing houses continue to crop up: as many as fifty in this year alone. New bookshops appear, bolstered by their cafés. Unlike in Canada, where literary and cultural events are regularly attended by older adults, the Ukrainian audience skews young: the most active age range for exhibition attendance is twenty to thirty-five, the majority women.

At this moment of national peril, literature has been taking on a new role. “It helps us understand the sheer diversity of Ukrainian experience,” said Yuliia Kozlovets, director of the IBAF. That experience now includes white-collar professionals who left their jobs to fight on the front lines; it includes refugees forced to flee for their lives; it includes people across a vast regional diversity who experience this war in different ways. “Literature,” Kozlovets said, “is our way of translating our experience to ourselves.”

On our last day in Kyiv, we visited the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, which is nestled into the high bank of the Dnipro River in the Pechersk Hills. A gleaming thirty-metre-high candle-like monument directed my gaze skyward as I descended into the Hall of Memory, which commemorates the victims of the Holodomor, a man-made famine that killed millions of Ukrainians in 1932–33.

After Ukraine’s incorporation into the USSR in 1922, the Soviet regime sought to extinguish the embers of Ukrainian nationhood. Writers, church officials, and educators suspected of nationalist sympathies were arrested or purged. In the 1930s, the Kremlin collectivized agriculture and imposed punishing grain quotas that stripped Ukrainian farmers of their crops; those who dared to collect leftover grain from their own fields risked imprisonment in labour camps or even execution. Stalin’s economic and cultural policies were designed to crush Ukrainian national consciousness and secure the republic’s total submission to Moscow.

In the Hall of Memory, I leafed through thick books containing the names of Stalin’s victims. I ran my fingers through bowls of sawdust, bark, and dirt—the “food” that kept some Ukrainians alive, while many others starved to death. Juxtaposed against the historical story of the Holodomor were videos of more-recent imperial aggression: in one, Ukrainian women demonstrated how in 2022 they placed family heirlooms and traditional Ukrainian dresses in pickle jars and buried them in gardens, to save them from pillaging Russian soldiers.

As I moved through the circular hall, reading about Stalin’s attempts to starve Ukrainians into accepting the “truth” of their Russianness, I felt vast levers of history swinging into alignment. For more than three years, we in Canada have struggled to make sense of the largest war in Europe since World War II. One dominant explanation, the so-called “offensive realist” thesis advanced by John Mearsheimer, places the blame directly on the West: NATO’s creeping advance to Russia’s doorstep, and the alliance’s flirtation with Ukraine, provoked Putin into taking self-defensive action.

But the Holodomor museum told a very different story. Here, we learned that Russian attempts to extinguish Ukrainian identity did not begin in 2022, or even 2014, but at least a century before, in a genocidal campaign that killed untold millions. Unlike the Nazi genocide of Jewish people, the Soviet Union’s brutal conduct during the Holodomor went unpunished by the international community. There was no Ukrainian equivalent to the Nuremberg trials. We have no cultural shorthand for memorializing this genocidal violence: there is no Schindler’s List for the Holodomor.

Instead, those of us outside Ukraine have demonstrated a pattern of forgetting and passivity. When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, the pattern held. Putin gambled that it would hold again in 2022, and whether he was right or wrong remains an open question. But what this history reveals is not that Western belligerence provoked Russia into lashing out, but something like the opposite: that an utter lack of consequences for its century-long slaughter of Ukrainians has all but guaranteed that Russia will continue its pattern.

In Ukraine, where national development was stunted by decades under Soviet rule, this history felt far too recent: the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide only opened in 2009, and a large part of it was still under construction. This museum was the most obvious example of a people who were performing the work of nation-building through memorialization, although other examples of this work were visible everywhere we went. Scenes of Russian violence were being converted, with incredible speed, into sites commemorating national identity.

I thought of the blown-out highway in Irpin, now a kind of real-world art installation, memorializing resistance to Russia’s attempted invasion of Kyiv in 2022. I thought of the Wall of Remembrance in Bucha, engraved with the names of more than 500 civilians—including 116 bodies discovered in a mass grave—who were massacred during the Russian occupation of 2022. I thought of that horrific school basement near Chernihiv, on its way to becoming a museum. Each of these sites, and countless others, memorialized moments of a catastrophe that was still in the process of unfolding. They were discrete nodes in an architecture of national becoming.

Every air strike, every wall pockmarked with bullet holes, every act of violence and depravity created another visible marker of Ukrainian identity, another physical manifestation of the difference between Russia and Ukraine, another promise of redemption. With every missile and every drone launched, Putin’s dream of a unified Ukraine and Russia receded a little further into the background.

Night came on quickly as I zigzagged back to my hotel, and I became conscious of the ghosts and zombies spilling into Kyiv’s squares. It was October 31. Children were in high spirits, younger ones dressed up as cats and robots, older ones as naughty angels, Jokers, the ghost-face killer from Scream. Teens were filming TikToks, roughhousing, flirting, irrepressible, still in the white morning of their lives. They fake-stabbed one another, acted out elaborate pantomimes of violent death.

Not far away, real-life monsters were plotting their next attack, calculating drone and missile vectors, picking their targets, choosing their moment. But tonight was Halloween, and for the children of Kyiv, the war would have to wait.