Archie Mitchell,Business reporterAnd

Natalie Sherman,Business reporter

Reuters

ReutersDonald Trump has vowed to tap into Venezuela's oil reserves after seizing President Nicolas Maduro and declaring the US would “run” the country until a “safe” transition.

The US president wants American oil companies to invest billions of dollars in the South American country, which has the largest crude oil reserves on the planet, to mobilize largely untapped resources.

He said U.S. companies would repair Venezuela's “severely damaged” oil infrastructure and “start making money for the country.”

But experts have warned of huge problems with Trump's plan, saying it would cost billions and take up to a decade to deliver significant increases in oil production.

So can the US really take control of Venezuela's oil reserves? And will Trump's plan work?

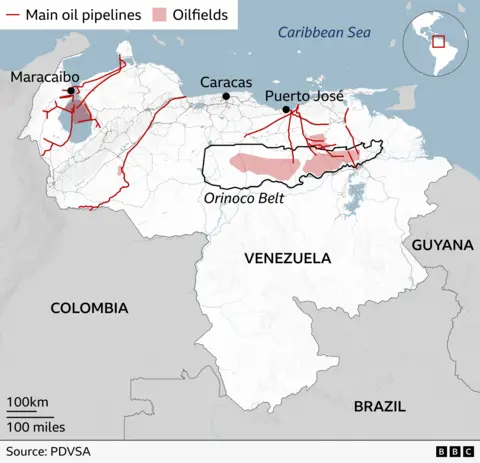

Venezuela, with oil reserves estimated at 303 billion barrels, is home to the world's largest proven oil reserves.

But the amount of oil the country actually produces today is minuscule in comparison.

Production has fallen sharply since the early 2000s, when former President Hugo Chavez and then the Maduro administration tightened controls over state oil company PDVSA, leading to an exodus of more experienced employees.

While some Western oil companies, including U.S. firm Chevron, are still active in the country, their activities have declined significantly as the U.S. has expanded sanctions and targeted oil exports in a bid to limit Maduro's access to a key economic lifeline.

The sanctions, which the US first imposed in 2015 during President Barack Obama's administration over alleged human rights abuses, have also prevented the country from investing and obtaining the components it needs.

“The real problem they have is their infrastructure,” says Callum McPherson, head of commodities at Investec.

Venezuela was producing about 860,000 barrels a day in November, according to the latest report from the International Energy Agency.

That's barely a third of what it was 10 years ago and less than 1% of global oil consumption.

The country's oil reserves consist of so-called “heavy, sour” oil. It is more difficult to process, but is useful for the production of diesel fuel and asphalt. The US typically produces “light, sweet” oil used to make gasoline.

Ahead of the strikes and Maduro's capture, the US also seized two oil tankers off the coast of Venezuela and ordered a blockade of sanctioned tankers entering and leaving the country.

Homayoun Falakshahi, senior commodities analyst at data platform Kpler, says the main obstacles for oil companies hoping to exploit Venezuelan reserves are legal and political.

He told the BBC that those hoping to drill in Venezuela would need an agreement with the government, which would not be possible until Maduro's successor comes to power.

Then companies will have to invest billions in the stability of the future government of Venezuela, Mr. Falakshahi added.

“Even if the political situation is stable, this process takes months,” he said. Companies hoping to take advantage of Trump's plan will need to sign contracts with the new government once it is in place before beginning the process of ramping up investment in Venezuela's infrastructure.

Analysts also warn that it will take tens of billions of dollars, and possibly a decade, to restore Venezuela's production to previous levels.

Neil Shearing, chief economist at Capital Economics, said Trump's plans would have a limited impact on global supplies and therefore oil prices.

He told the BBC there are “a huge number of hurdles to overcome and the time frame for what will happen is so long” that oil prices in 2026 are likely to be little changed.

Mr Shearing said companies would not invest until Venezuela had a stable government and that the projects would not be completed for “many, many years”.

“The problem has always been decades of underinvestment and mismanagement, and they are very expensive to extract,” he said.

He added that even if the country could return to its previous level of production of about three million barrels per day, it would still remain outside the world's 10 largest producers.

And Mr Shearing pointed to high production from OPEC+ countries, saying the world was currently “not suffering from a shortage of oil”.

Chevron is the only U.S. oil producer still operating in Venezuela after receiving a license under former President Joe Biden in 2022 to operate despite U.S. sanctions.

The company, which currently accounts for about a fifth of Venezuela's oil production, said it places special emphasis on the safety of its employees and complies with “all relevant laws and regulations.”

Other major oil companies have so far remained publicly silent on the plans, with only Chevron commenting.

But Mr Falakshahi said oil bosses would hold internal talks about whether to pursue the opportunity.

He added: “The desire to go somewhere is related to two main factors: the political situation and local resources.”

Despite the highly uncertain political situation, Mr Falakshahi said “the potential prize may be too big to avoid.”