Our study benchmarks four state-of-the-art long-read assembly software programs: (1) HiCanu v2.2 (ref. 14), (2) hifiasm-meta v0.3 (ref. 11), (3) metaFlye v2.9.5 (ref. 13) and (4) metaMDBG v1 (ref. 12), based on their assembly performance of 21 PacBio HiFi metagenomes (Supplementary Table 1). We include HiCanu in our analysis despite the fact that it was originally developed for genome assembly as it has recently been benchmarked against hifiasm-meta and metaFlye11. Of the 21 metagenomes we include in our benchmarks, 13 represent those that were also used by the authors of at least one assembly algorithm to evaluate performance, and correspond to mock communities (Zymo-HiFi D6331 and ATCC MSA-1003) and anaerobic digesters (AD2W1, ADW20 and ADW40), as well as gut samples from humans (Human O1, Human O2, Human V1 and Human V2), chickens and sheep (Chicken, SheepA and SheepB). The remaining eight are novel HiFi metagenomes from the surface ocean (sample names start with HADS)32, a key biome that was not included in previous benchmarks and represents a complex ecosystem with relatively little genomic representation (Supplementary Table 1).

Investigating the agreement between individual long reads and assemblies they support requires the alignment of reads to resulting contigs. For this task, our study uses minimap2, a high-performance mapping software designed to align long reads to reference sequences33. While short-read alignment software such as Bowtie2 (ref. 34) or BWA35 is typically used to perform end-to-end alignments, minimap2 allows premature ends in read alignments and can map the remainder of the read to another reference location. This so-called read clipping procedure is a critical tool to identify locations in the final assembly that is poorly supported by individual long reads. To gain quantitative insights into assembly artifacts, we developed ‘anvi-script-find-misassemblies’36, a script that comprehensively summarizes locations and frequencies of read clipping events, in which long reads are split systematically by the mapping software to maximize agreement between reads and assemblies, in addition to regions in contigs that are not supported by individual long reads.

Assembly errors are common to all long-read assemblers

Instances in which the vast majority of long reads are clipped at the same nucleotide position are strong evidence that the final assembled sequence contains an error. However, quantifying the number of errors in a given assembly is not as straightforward as counting the clipping events as a single assembly error may result in multiple clipping events associated with neighboring nucleotide positions in the reference sequence (Fig. 1a). To minimize false positives in our results, and exclude clipping events due to within-population biological variation, our analyses below primarily focus on locations in long-read assemblies with a 100% clipping rate.

a, A schematic representation of long reads mapping to a contig with multiple types of read disagreement with the reference, including INDELs and SNVs representing more than half or all the coverage, and clipping events spanning the entire coverage. All metrics for b–g are normalized by assembly size and exclude the two mock community metagenomes (n = 19 assemblies). For all box plots, the box represents the interquartile range (IQR), the central line indicates the median and whiskers extend to 1.5× the IQR. b, Number of clipping events supported by at least 10 reads. c, Number of regions over 1,000 bp with no apparent coverage. d,e, Number of SNVs representing >50% (d) or all (e) of the coverage at a given locus. f,g, Distribution of INDELs >50% of the coverage (f) or all of the coverage (g). h, Length distribution of circular contigs by each assembler. The darker color represents the distribution of circular contigs with at least one clipping event.

The assembly metrics differed greatly between sample types and assembly algorithms. For instance, all human gut metagenomes were assembled to a similar total size by all assemblers, but not the surface ocean samples (Supplementary Table 2), for which metaMDBG produced 610% more assembled sequences compared with HiCanu on average. We found high-confidence read clipping events (that is, 100% clipping at locations with at least 10× coverage) in at least one sample from each assembler (Supplementary Table 2). However, the frequency of these events normalized by the assembly size showed that metaFlye and metaMDBG generated up to 180 times more clipping events compared with HiCanu and hifiasm-meta for the same samples (Fig. 1b). The number of clipping events was particularly high in the surface ocean samples, in which assemblies from metaMDBG had over three orders of magnitude more clipping events compared with those from hifiasm-meta (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, clipping events affected up to 5.6% of contigs longer than 10,000 nucleotides reported by metaMDBG with an error rate up to 46 per 100 million base pairs (Mb) of assembly. We also computed the number of regions longer than 1,000 bp with no apparent coverage by individual long reads and found that the occurrence of regions that are not supported by any read was as pervasive as clipping events. While this issue also affected all assemblers (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 2), metaMDBG led the pack with up to 5.3% of all contigs longer than 10,000 nucleotides with zero-coverage regions.

The reporting of contig circularity was a common feature of all assemblers; however, the number of circular contigs in final assemblies also varied between algorithms (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Table 2). MetaMDBG generated substantially more circular contigs than other assemblers, notably from surface ocean metagenomes. Overall, we found at least one clipping event for a large proportion of circular contigs reported by metaMDBG (Fig. 1h), which, in some cases, represented up to 77% of the circular contigs in a sample (for example, the marine sample HADS 013; Supplementary Table 2).

In addition to the clipping events, we reported the frequency of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertion–deletion events (INDELs) in the assembled contigs that were not fully supported by the long reads. We classified such cases into two categories: (1) ‘minority variants’, where the final assembly included a nucleotide or an INDEL that did not match the most frequent variant in the supporting long reads (Fig. 1a,d,f), and (2) ‘unsupported variants’, a more severe case in which the final assembly included a nucleotide or an INDEL that did not occur in any of the long reads at that position (Fig. 1a,e,f). After normalizing based on the assembly size, HiCanu and hifiasm-meta had the most minority variants, while metaFlye and metaMDBG had the most unsupported variants. The latter case affected thousands of genes in all assemblies (Supplementary Table 2), leading to genes with incorrect amino acid sequences owing to the impact of INDELs on open reading frames37,38. Our detailed investigation of individual clipping events associated their occurrence with a few recurring classes of erroneous reporting of contigs, including chimeras, premature circularization, haplotyping issues, false duplications and nonexistent sequences, for which we offer an incomplete list of examples below.

Chimeric contigs

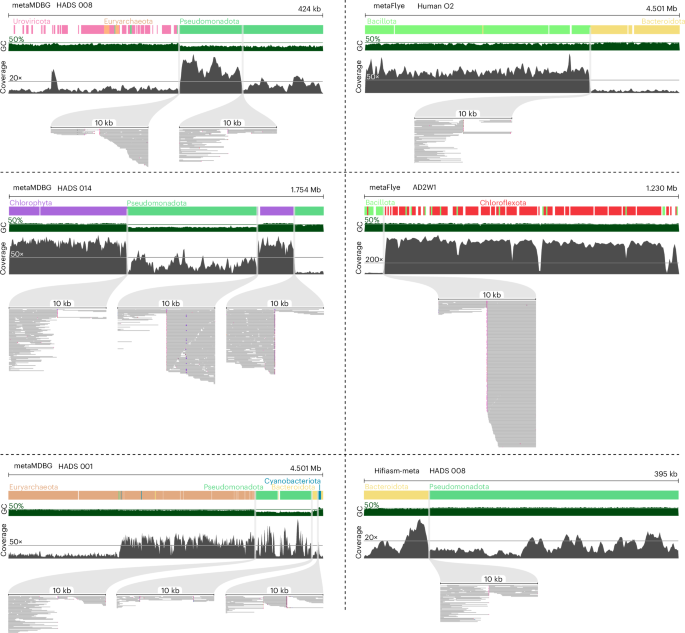

Our inspection of contigs with a high proportion of read clipping events revealed chimeric contigs. In some cases, chimeras brought together sequences from taxa that belonged to distinct phyla (Fig. 2). Most chimeras brought together sequences from two distinct taxa, but cases that merged sequences from more than three organisms were not uncommon (Fig. 2), and they sometimes combined sequences from distinct domains of life. In one extreme case, metaMDBG formed a sequence that included regions from organisms that originated from Euryarchaeota, Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota and Cyanobacteria (Fig. 2). We acknowledge that the list of contigs we surveyed here for chimerism is far from exhaustive; furthermore, relying on clipping events alone may occasionally miss chimeric contigs. For instance, we stumbled upon a suspiciously long contig. Even though the frequency of read clipping events did not flag this 7.38-Mb contig, anvi’o assigned it a redundancy score of 100% because it contained two copies of every bacterial single-copy core gene. Our manual inspection showed that the contig metaMDBG reported from the sample Human O1 conjoined two sequence-discrete Lachnospiraceae populations (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Six contigs from metaMDBG, metaFlye and hifiasm-meta. For each contig, we showed the GC content, coverage in the metagenomics reads used for their assembly and gene-level taxonomy computed with Kaiju and the nr_euk database. For each assembly breakpoint, we show a zoomed-in detail of the read mapping from IGV. In these subplots, the red arrows at the end of the mapped read indicate clipping and the coloring at the end of these reads indicates that the following portion of the read mapped to another contig and similar colors indicate that multiple reads continue to map on the same contig. The blue markers indicate large INDELs (>150 bp).

The highly dangerous nature of chimeric contigs for downstream analyses is dampened by the straightforward nature of their identification by anyone who carefully investigates their data: most chimeric contigs that erroneously connect genomic regions from two or more distinct populations can be easily identified using a series of well-understood indicators, such as sudden shifts in GC content, read coverage and gene-level taxonomy, or through unexpected inventories of single-copy core genes (SCGs). Nevertheless, with the increasing tendency of researchers to generate large metagenome-derived genome compendiums39,40,41,42,43, such evaluations are rarely, if ever, conducted. Thus, in an ideal world, the burden of resolving chimeras should never fall on the shoulders of the end users of assembly algorithms.

Premature circularization

To deliver one of the most sought after promises of long-read sequencing, most long-read assemblers contain built-in features to circularize contigs and report potentially complete microbial and mobile genetic element genomes. Premature circularization, the reporting of a contig as circular when it omits parts of the genome it originates from, is a form of error with dangerous downstream implications. Yet, our analyses showed that the algorithmic features that reconstructed circular contigs in long-read assemblers, especially metaMDBG, and to a lesser degree hifhasm-meta, were far from reliable.

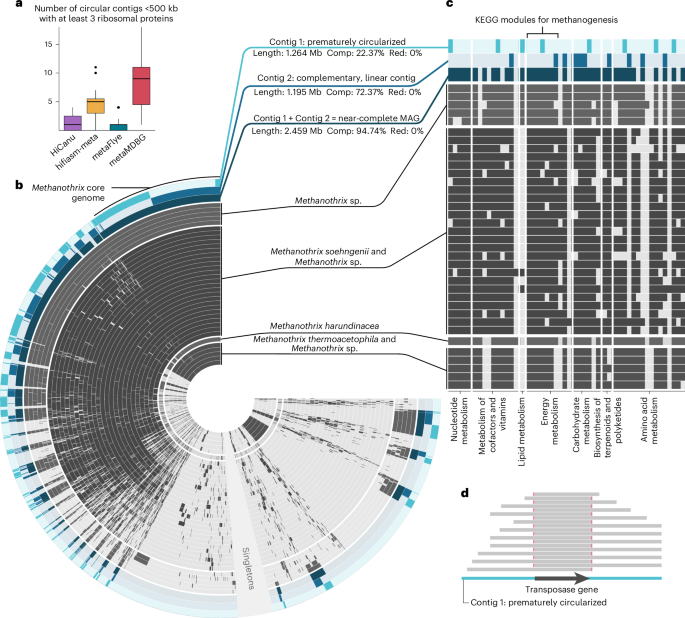

For instance, an archaeal genome that belongs to the genus Methanothrix recovered from the AD Sludge sample as a circular genome by hifiasm-meta represents a clear example of the nature and implications of premature circularization. Through an analysis with additional genomes from the RefSeq collection of the US National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), we confirmed that the circular genome was missing a large fraction of the core Methanothrix pangenome (Fig. 3b, light blue), including key metabolic modules for methanogenesis that were common to all Methanothrix genomes (Fig. 3c). In this case, early circularization seemed to have occurred near a transposase (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 2). Nearly all the reads clipping on either side of the transposase had supplementary mapping to another contig in the assembly output (Fig. 3b,c, medium blue) encoding the missing metabolic module. The combination of the circular genome and the additional contig matched the other genomes in the genus-level pangenome (Fig. 3b,c, dark blue), suggesting that both contigs belonged to the same population, and neither of them were circular by themselves.

a, Frequency of circular contigs under 500 kb with a minimum of 3 ribosomal proteins for each assembly, excluding the two mock communities (n = 19). The box represents the IQR, the central line indicates the median and the whiskers extend to 1.5× the IQR. b, A pangenomicanalysis of all publicly available Methanothrix genomes from the RefSeq database of NCBI completed with the so-called circular genome of Methanothrix assembled from the sample AD Sludge by hifiasm-meta (light blue), as well as a contig from the same assembly that corresponds to the rest of the missing Methanothrix genome (medium blue) and the combination of these two contigs (dark blue). c, KEGG metabolic module completion of all genomes and contigs in b. d, A schematic representation of the reads mapping over a transposase gene in the prematurely circularized contigs (light blue in b and c) showing the lack of read support around the gene; the full figure is available in Supplementary Fig. 2. MAG, metagenome-assembled genome; Comp, completion; Red, redundancy of genomes based on archaeal single-copy core genes.

Comparing the overall accuracy of circularization across assemblers is difficult. For instance, low completion estimates based on single-copy core genes can serve as a quick filter, but not all prematurely circularized genomes will have low completion estimates as missing genomic content will not always contain single-copy core genes. Length comparisons between circular contigs and known genomes in public databases could offer another means of scrutiny, but this strategy will not be effective against poorly studied clades, or those that have no representation in genome repositories. Nevertheless, here we conservatively assumed that circular contigs that were under 500 kb and contained at least 3 ribosomal proteins were most likely circularized erroneously. While this criterion is useful as a proxy for identifying potential assembly artifacts, we note that some naturally occurring small genomes may also meet these criteria44,45. Despite this caveat, we reasoned that the frequency with which such contigs appear across assemblers could provide a useful approximation of each assembler’s tendency toward premature circularization. Within this framework, metaMDBG reported about twice as many circular contigs than hifiasm-meta, and about four times more circular contigs than HiCanu and metaFlye (Fig. 3a). Assuming that easily identifiable events of premature circularization errors are reasonable proxies for the rate of all premature circularization errors, this result suggests that metaMDBG and hifiasm-meta are more prone to premature circularization errors compared to other assemblers, such as HiCanu and metaFlye. Our estimates of the rate of false circularization come very close to the benchmarking results shared by the authors in the original metaMDBG publication12, in which they report two times more circular contigs than hifiasm-meta and four times more circular contigs than metaFlye from the human gut. While the high rate of circularization is presented as a strength of metaMDBG in comparison to other assemblers12, our observations suggest that the higher rate of circularization may be a result of a higher tendency to report noncircular elements as circular (Figs. 1 and 3, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2).

Given the vast difference in quality and perception between a draft genome and a circular genome, it is essential for assembly algorithms that promise circular genomes to be conservative in their decision-making. The identification of prematurely circularized contigs in assembly results will be a notoriously difficult task for end users, especially when the missing genomic context is relatively short, or circular contigs represent plasmids or viruses. Thus, it would be ideal if the circular sequences are validated more rigorously by the assembler before the final reporting.

Haplotyping errors, false duplications and nonexistent sequences

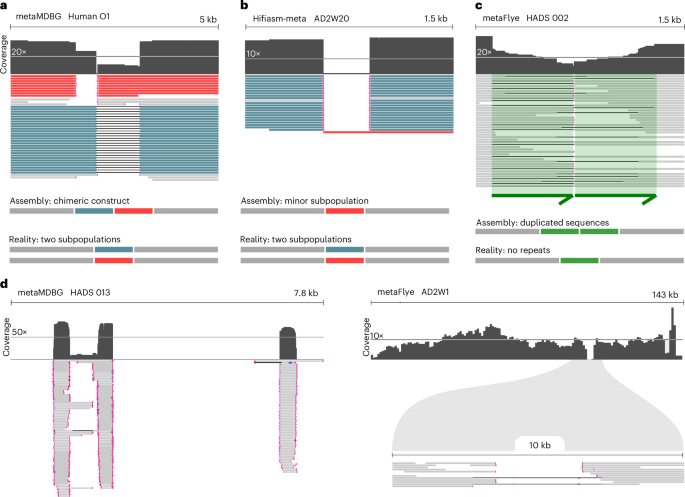

Accurate reconstruction of genomic variation is essential to associate within-population structural differences to ecological or evolutionary phenotypes. However, resolving genomic regions that differ between otherwise very closely related subpopulations is a major challenge for de novo assemblers46. Assemblers may resolve such structural complexity through three approaches: (1) by reporting separate contigs for variable sequences and conserved regions that flank them, (2) by reporting the most prevalent variable region along with the flanking conserved regions in a single contig and alternative regions in shorter contigs or (3) by duplicating conserved flanking regions in multiple contigs that describe each of the variable regions and their surroundings as separate contigs in a haplotype-aware fashion. Our survey of long-read assembly results revealed unexpected haplotyping decisions in multiple recurrent forms. In some cases, assemblers concatenated subpopulation-specific variable regions flanked by conserved loci, rather than reporting only one of them accurately (Fig. 4a). As a result, long reads that map to these regions are clipped at the end of their respective subpopulation sequence, a phenomenon that is also known as haplotypic duplication27,29. In other cases, the final contig represented a variable region found in a minor subpopulation supported by a small number of long reads or a single one (Fig. 4b), violating the logical expectation to recover a consensus sequence that represents the most abundant subpopulation.

a, A chimeric sequence assembled from two subpopulations. At a conserved locus, two subpopulations existed with their own and distinct sequence. The assembled contig contains all or a part of each subpopulation-specific sequence resulting in a chimeric construct. b, Another example of a variable genomic site, but in this example, the contig sequence contains the sequence of a very minor subpopulation, supported by only one read. c, Duplicated sequence found only in the assembly, not supported by any long reads. d, Two contigs assembled from metaMDBG (left) and metaFlye (right) presenting large regions with no coverage. We BLASTed these regions back to the long reads and found no hits. Coverage visualization was exported from the anvi’o interactive interface (left) or the IGV software (right) and the read mapping visualization was from IGV as well. INDELs smaller than 150 bp as well as mismatches are not shown in the mapping. Red markers at the end of reads indicate read clipping.

We also identified cases in which assemblers reported false genomic duplications in assembled contigs that were not supported by any long read. Such false repeats were often manifested by high-frequency read clipping events and appeared as long direct repeats that had low likelihood to be present in the target genomic context owing to the sudden decrease in read coverage and/or massive inserts in mapped reads (Fig. 4c). Yet another anomaly was the reporting of sequences that did not exist. Searching for zero-coverage regions from contigs that are longer than 500 bp against the database of raw long reads using the NCBI’s Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) with the flag ‘-dust no’ to include sequences of low complexity (Supplementary Table 3), we confirmed that the assembly outputs by metaMDBG and metaFlye occasionally included up to over-5,000-bp-long regions that have no homology to any of the input long reads (Fig. 4d). We further confirmed this observation by comparing the k-mer (k = 21) content between these regions and long reads, and found that over 90% of the k-mers in zero-coverage regions were absent in the long reads (Supplementary Table 3). False duplications and reporting of nonexistent sequences in assembly results are unexpected behaviors from any assembler and can lead to spurious open reading frames or the omission of genuine ones.

Excessive repeats

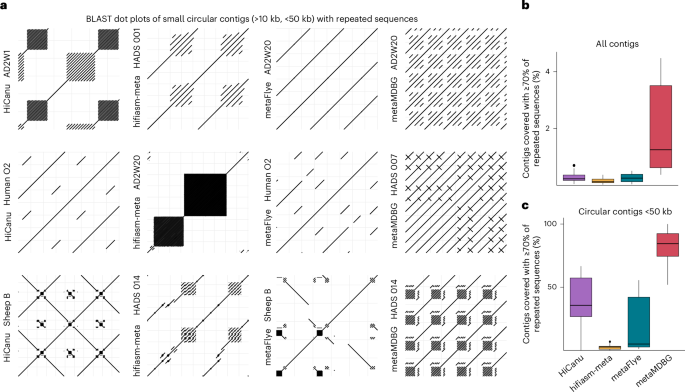

A recurrent and puzzling observation throughout our manual inspections of assembly results was the astonishing number of repeats that occasionally made up the entirety of some contigs. Yet, these repeats were not caught by our survey of read clipping event frequencies to mark regions of concern as repeats rarely resulted in 100% read clipping events to pass our filter. Thus, we characterized repeats without any read mapping data but by aligning each contig to itself. We marked any region of a contig as a ‘repeat’ if it was longer than 200 bp and occurred multiple times in the same contig with at least 80% identity, based on observed similarity in naturally occurring repeats47. Our survey of the frequency and distribution of such repeats across all contigs showed that each assembler reported contigs with repeats. As repeats are common in nature, and the improved ability to resolve repeats is one of the strengths of long-read sequencing, this finding alone is not concerning. However, the nature of repeats in assemblies revealed by dot plots often showed unexpectedly intricate patterns, suggesting a high likelihood that they were assembly artefacts, rather than natural genomic organizations (Fig. 5a). While naturally occurring tandem repeats, inversions or palindromes could lead to similar dot plots, our manual inspection of individual cases revealed a variety of errors that spanned from duplicated reporting of known circular plasmids to contigs with multiple repeats that are not supported by any long read.

a, Dot plots of reciprocal BLAST results from 12 short circular contigs showing high amounts of repeated sequences. b,c, Proportion of contigs with at least 70% of their length duplicated at least once. Result computed for all contigs (b) and only for circular contigs under 50 kb (c) across all assemblies, excluding the two mock communities (n = 19). For all box plots, the box represents the IQR, the central line indicates the median and whiskers extend to 1.5× the IQR.

Repeats differed in their length, identity and frequency across algorithms. The per-sample average length and sequence identity of repeats varied between 600 bp and over 1,450 bp, and 88% and 92%, respectively. MetaMDBG generated more repeats than any other assembler (Fig. 5b), up to over 300,000 repeats in a single assembly (Supplementary Table 2), exceeding the number of repeats reported by HiCanu for the same sample 235 times. The average length of repeats was relatively short, yet we found repeats that were up to 225,520 nucleotides long, and repeats occurred as much as over 990 times in a single contig (Supplementary Table 2). To summarize the number and proportion of contigs reported by each assembler with an excessive number of repeats, we conservatively searched for assembled sequences in which at least 70% of the sequence was composed of repeats. This search revealed that metaMDBG generated on average 2% of contigs with a high number of repeats, a rate that was over 14 times higher than its runner up, hifiasm-meta (Fig. 5b). When we limited our survey to circular contigs under 50 kb, which represented over 90% of all circular contigs, the proportion of repeat-rich contigs skyrocketed across all sample types for all assemblers, with the exception of hifiasm-meta (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 2). For instance, 87% of all circular contigs under 50 kb reported by metaMDBG were largely composed of repeats, and in some samples, such as chicken, this number reached 100%, suggesting that artifactual repeats represent at least one of the factors that lead to false circularization (Fig. 5c). Marine metagenomes were particularly difficult for all assemblers. In this sample type, metaMDBG reported the highest number of circular contigs (Supplementary Table 2); however, 92% of them under 50,000 bp were composed of repeats (Supplementary Table 2). While metaFlye performed as well as hifiasm-meta in most other sample types, up to 55% of circular contigs metaFlye generated from marine metagenomes were largely composed of repeats (Supplementary Table 2).

These results show that the exciting prospects of recovering complete and circular plasmid and virus genomes from long-read sequencing of complex metagenomes are still far from being realized, and that the state-of-the-art long-read assemblers often fall short when handling short circular elements.

Mock datasets are useful but can yield misleading insights into the accuracy of algorithms in real-world applications

Popular mock datasets such as Zymo-HiFi D6331 and ATCC MSA-1003 are commonly used for benchmarking long-read assemblers. While their known composition constitutes a reasonable starting point, the mock datasets do not represent the complexity of the natural samples, as also noted by the authors of metaFlye13. Their utility to test assemblers is further reduced when benchmarks that use mock communities simply align contigs that emerge from the assemblies to reference genomes without comprehensive reporting of other assembly metrics11,12,13. For instance, while hifiasm-meta reports favorable outcomes given the reference genomes in mock datasets11, in our tests, the algorithm generated massive assemblies for each mock dataset, in which the final assembly was 270 Mb instead of the expected size of 93 Mb for the Zymo-HiFi D6331, and it was 948 Mb instead of the expected size of 66.44 Mb for the ATCC MSA-1003, resulting in the lowest N50 values and the highest number of clipping events across all assemblers. Given its performance with the mock datasets, one may expect hifiasm-meta to perform poorly in its applications to complex metagenomes. Yet, in marine samples, hifiasm-meta was first in N50, and second to metaMDBG in assembly size with two orders of magnitude fewer clipping errors, suggesting that the performance of an assembler with mock communities may not predict its performance with real-world datasets.

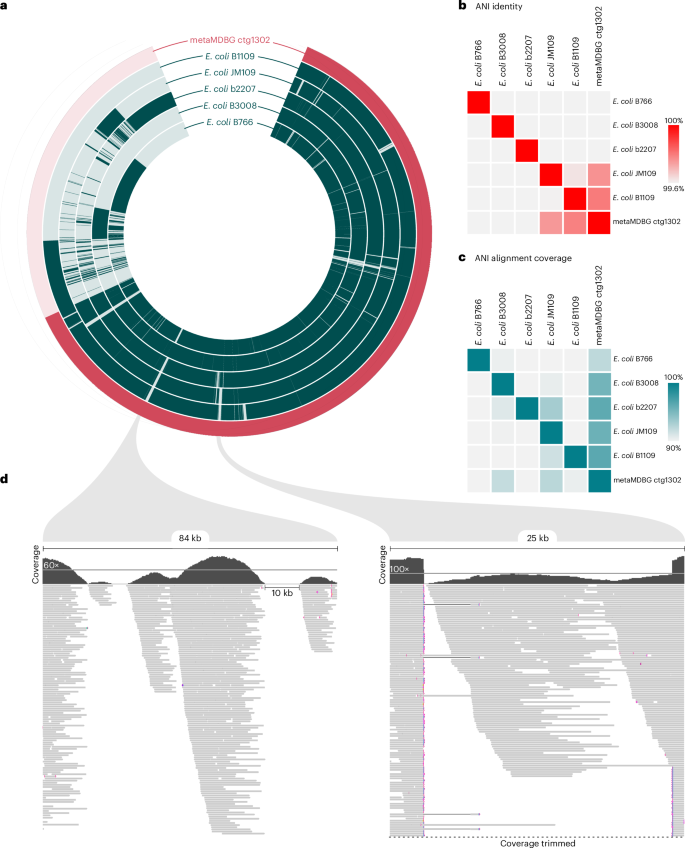

While mock communities do not represent the diversity and complexity found in real-world samples, they shine in one fundamental way: the known genomic makeup of input organisms to identify glaring issues post-assembly. The Zymo-HiFi D6331 includes five different strains of Escherichia coli, which yields sequencing data with complex cases for assemblers owing to the presence of highly conserved and divergent genomic regions. HiCanu and hifiasm-meta were both successful at reconstructing at least one of the five E. coli genomes (Supplementary Fig. 3), while metaMDBG reported a circular contig that corresponded to a chimeric genome (Fig. 6). On the basis of pairwise average nucleotide identity (ANI) comparisons, this genome appeared to be most similar to B1109, one of the E. coli strains in the Zymo-HiFi D6331 mock dataset (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 4). However, the pangenome of the five E. coli genomes and the metaMDBG circular contig showed that it was not only missing a portion of the B1109 genome, but also including genomic regions exclusive to other E. coli strains and absent in B1109 (Fig. 6a). Clipping events also captured chimeric regions and revealed ~10-kb locus with no coverage (Fig. 6c,d). That region without coverage was duplicated in two other contigs, suggesting that long reads were preferentially recruited there (Supplementary Table 5). Using ANI values calculated from local alignments of assembled contigs to reference genomes can mask critical assembly errors, such as phantom sequences, chimeras and unexpectedly large assembly outputs, and invalidate perhaps the only useful aspect of mock datasets while inflating the reported accuracy of assembly algorithms.

a, A pangenome analysis of the E. coli reference genome used in the Zymo mock community and the E. coli circular genome assembled by metaMDBG. Each layer corresponds to a genome, and the coloring represents the presence or absence of a gene cluster from each genome. The gene clusters are organized by the synteny of genes in the metaMDBG contig. b,c, Genome pairwise average nucleotide identity (b) and alignment coverage (c). d, Details of the long-read mapping over two genomic regions highlighted in a. These regions included genes not found in E. coli B1109 (closest reference genome by ANI metrics), but rather found in other E. coli genomes.