A new kind of gold rush is sweeping the West, and this time the prize is not minerals, but megawatts. From Phoenix to the Front Range in Colorado, data centers are popping up with huge demands for power and water. In the new reportRegional environmental group Western Resource Advocates (WRA) warns that without stricter measures, the financial and environmental costs could fall on ordinary households.

New data centers in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah are expected to lead to a surge in resource use that will raise consumers' energy bills and jeopardize climate goals. By 2035, the emergence of new data centers could lead to a surge in electricity demand in the Inner West by around 55 percentwarns WRA.

The industry's unprecedented energy needs are at risk of being wiped out decarbonization targets in several states. Energy experts say astronomical electricity demands could keep fossil fuels like coal and gas in use for longer. NV Energy, Nevada's major utility, now expects carbon dioxide emissions to rise 53 percent over 2022 estimates due to the growth of new data centers.

Deborah Kapiloff, WRA clean energy policy advisor and author of the new report, highlights the incredible scale of additional energy needed to power the region's technology infrastructure boom. She estimates that over the next decade, planned data centers in the West will burn enough electricity annually to power 25 cities the size of Las Vegas.

Who covers the electricity costs in a data center?

In some cases, industry passes on these energy costs to the public. Kapiloff explains that customers will likely bear the burden of costly new energy infrastructure because utilities typically spread construction costs across all users. Given the unprecedented demand of energy-hungry data centers, this logic does not work. “When the client is so big, the old assumption that ‘growth helps everyone’ doesn’t work,” she said.

In Colorado, regulators are struggling to keep up. John Gavan, a former member of the Colorado Public Utilities Commission, says utilities in his state may have to roughly double their total electricity production within five years to cope. “The scale here is staggering,” he says. “A single hyperscale data center can consume 10 percent or more of an entire staff’s workload.”

Officials say current pricing rules could lead to higher costs for electricity from new data centers for residential customers. Joseph Pereira, deputy director of the Colorado Office of Utility Consumer Advocacy, says that could mean a 30 to 50 percent increase in household rates — and those costs could double or even triple over the long term.

Pereira also highlights the risks of building new power generation and transmission centers for data centers that may never be built. “If we build the infrastructure and then the load on the data centers doesn't show up, someone will be left responsible (for the costs),” he says. “Today it’s existing customers.”

Water on the line

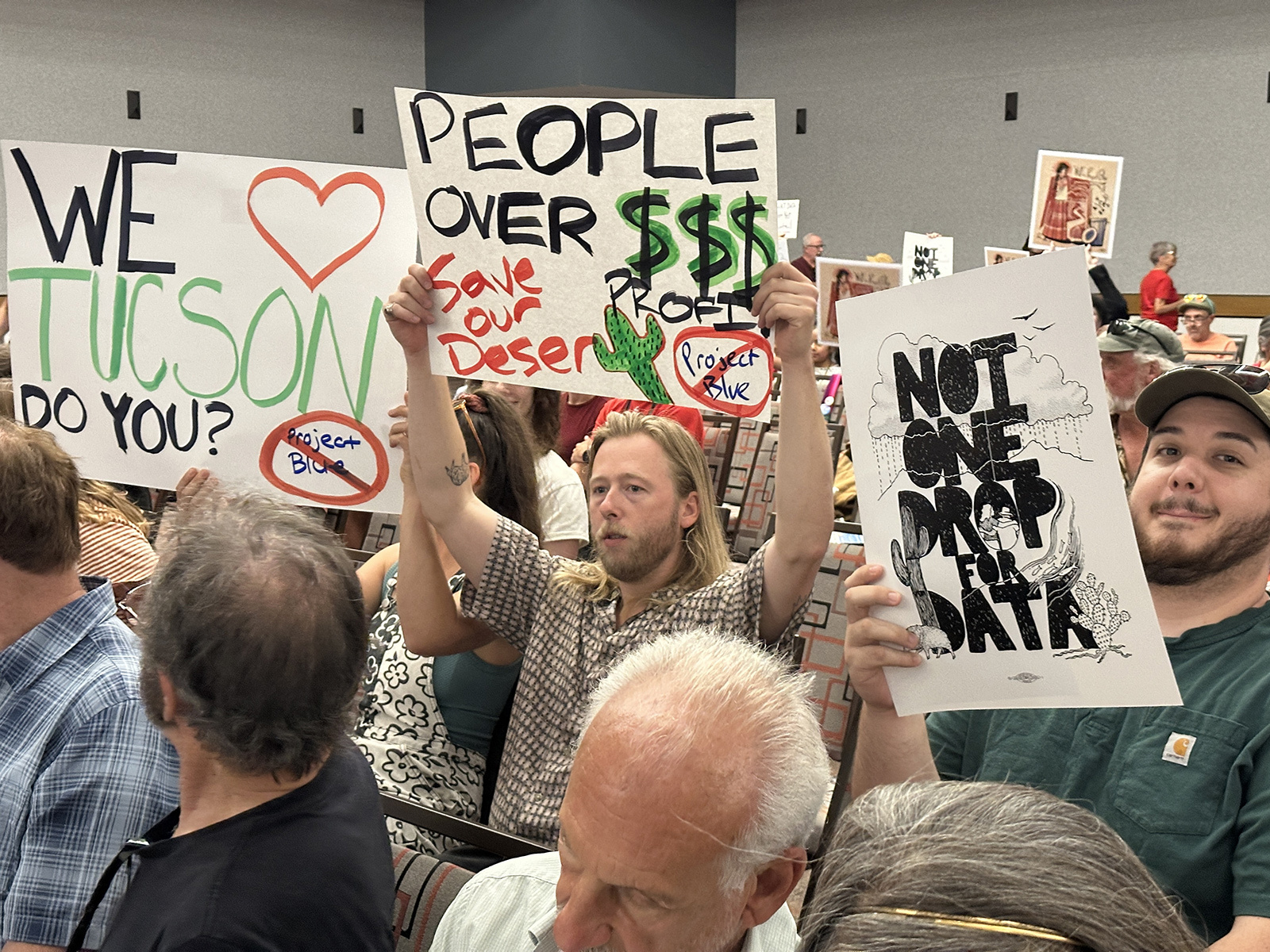

Data centers also have high water requirements. Near Tucson, Arizona, a proposed data center in the Sonora Desert of Pima County has become a community flashpoint due to the project's high demands in an already water-stressed region. Initial designs suggest the controversial Blue Project will require “millions and millions of gallons,” says Pima County Executive Jennifer Allen, although official numbers have not been released.

“Getting people out of the water is a clear line that people agree on, even in this divided country,” said Duke University lecturer Allegra Jordan. As a public advocate for data center projects, she has repeatedly seen local officials asked to approve projects without key information about their impacts.

In Arizona, community backlash to Project Blue led to a design change, and the developer now claims the new plans will use little or no water, although Allen says she hasn't seen any documentation to support that claim. Kapiloff notes that water transparency is a common issue. “We don’t have enough information about how much water data centers use in total—it’s a big black box,” she says.

Where one can estimate the potential water required for new data centers, the scale is sobering. For example, in Nevada, currently proposed new data centers would consume approximately 4.5 billion gallons of water in 2030 if built with traditional cooling. By 2035, that number will rise to 7 billion gallons—the equivalent of water for nearly 200,000 people.

Fast deals, secret facts

However, the speed and secrecy of data center deals often keep even government officials in the dark. In the first phase of Project Blue in Arizona, Pima County Supervisor Jennifer Allen says she and the rest of the board of supervisors were asked to vote on the proposal without access to full information about the project because of non-disclosure agreements signed by county staff that covered elected officials. “The game was shrouded in mystery,” she says.

Jordan believes communities deserve informed consent about what impact data centers will have on their energy bills, water use and environmental impact. “The moral question is whether people should have agreement about whether their energy bills will go up or how their water will be used,” she says.

She also notes that, lured by promised financial benefits, local governments sometimes do not fully disclose what incentives and incentives are available to data centers. “Oftentimes data center advocates say, ‘This will lead to new property taxes and new jobs,’” she says. “But a lot of communities don't really understand what they're giving up. And while the community government is the entity that gets that money, the people who pay, in terms of larger electric bills, are ordinary citizens.”

Building Better: A Guide to Responsible Development

In response to this growing pressure, some communities are taking precautions. For example, after the failure of Project Blue, the Pima County Board of Supervisors introduced new regulatory requirements, including NDA restrictions and a “sunshine period” when results must be made public before voting. Other potential measures the WRA recommends include energy efficiency requirements, eliminating tax incentives for data center development and prioritizing data center projects that include renewable energy generation.

Consumer advocates like Pereira are also working to ensure that high-load customers pay their own way, helping to shield existing customers from liability if proposed data centers are never built. The WRA report highlights key tools such as specialized rate classes designed to ensure large or unusual customers pay rates that reflect their unique impact, as well as requirements that data centers pay for their projected power needs even if demand declines or never materializes. Clean transition tariffs, or special electricity tariffs that help large energy users switch to cleaner energy, could help fund renewable energy projects to power data centers. Finally, creating standards that limit load during off-peak hours can help protect both taxpayers and resources.

Energy efficiency best practices and behind-the-meter approaches can also help. In Europe, innovative models include cluster of data centers under construction in Finland, which will use the generated heat to heat approximately 100,000 homes in Helsinki, and a data center in Norway, which provides hot water to support nearby aquaculture. These methods may work in the United States, too: a new development in San Jose, California, aims to become one of the most resilient data centers in the worldimplementing on-site energy sources and using waste heat to power equipment coolers.

While tools like these can help, without rapid reforms, even the best planning policies will not be able to prevent the consequences of rapid data center growth. Many communities face aggressive searches for data centers and still lack mandatory protections and transparent regulations that protect taxpayers from costs and protect the environment.

As Kapiloff says, “When these data centers are being built by some of the most highly capitalized corporations in the world, does it make sense to pass those costs on to ordinary people? I think the answer to that question is a resounding no.”

Western Resource Advocates is a regional nonprofit organization that fights climate change and its impacts to support the environment, economy and people of the West. The organization drives state action to advance policies that will create a healthier and more equitable future for all communities. As leading experts for more than three decades, WRA has been on the ground harnessing clean energy and protecting air, land, water and wildlife.