This article is part of “Innovations in: Type 1 Diabetes“, an editorially independent special report produced with financial support from Vertex.

More than 9.5 million people people around the world are living with type 1 diabetes, and this figure is growing rapidly everywhere, in all age groups. The burden of this autoimmune disease, whose risk includes premature death, is unevenly distributed: the disease is more deadly in low-income countries.

“The data speaks for itself,” says Stephanie Pearson, senior director of global accountability for the nonprofit Breakthrough T1D. “Type 1 [diabetes] are being diagnosed more often than ever before, but more in-depth research is needed to understand why these numbers continue to rise.” Scientists know that more education and awareness means more diagnoses. They are also studying additional possible reasons for this increase, including potential triggers that cause the body to kill its own insulin-producing cells. Bacterial and viral infections, diet, lifestyle and even pregnancy-related factors can contribute.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Ultimately, Pearson says, patients hope for a cure for diabetes, but they also need better access to advanced treatments, treatments for complications and technologies to manage their disease.

The growing burden of type 1 diabetes among young people

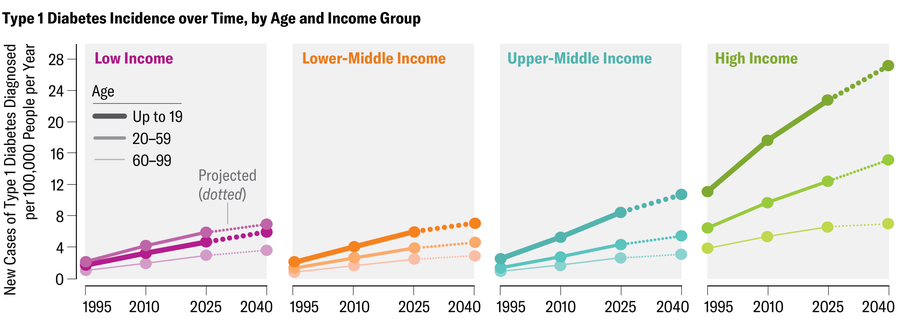

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is being diagnosed in more people than ever before – around half a million this year – and at increasingly younger ages. Over the past three decades, improvements in diagnostic tools and increased awareness have contributed to a steady increase in the number of people receiving a diagnosis of T1D in almost every country in the world. For people under 20, the sharpest increases were in high-income countries in the Middle East.

In low-income countries, where health systems are less equipped to detect and treat the disease, T1DM remains much more deadly. A 10-year-old child with the condition in the United Arab Emirates can expect to live until about 76 years old, about eight years less than the national average. However, in Niger, a 10-year-old child with T1D faces a completely different reality: that child can expect to live on average another ten years, having lost as much as 50 years.

Miriam Quick and Jen Christiansen; Source: T1D Index. (www.t1dindex.org) (data)

Type 1 on the rise

The number of people worldwide living with T1D is growing rapidly, driven by rising incidence combined with increasing life expectancy, decreasing mortality, and overall population growth. Rates are rising relative to population in both rich and poor countries and across all age groups. The growing burden is not limited to young people: it reflects both an overall increase in incidence and earlier diagnosis.

But the picture is uneven and the disparities are stark. Data show that in high-income countries, almost every person under 25 years of age is diagnosed with T1DM. However, the International Diabetes Federation and the T1DM Index estimate that only about two thirds of such cases are detected in low-income countries. Thus, the reported incidence among children and adolescents is much lower than expected, reflecting missed or late diagnosis. These numbers are simulated because more than half of countries do not have current data, highlighting the urgent need for better epidemiological research worldwide.

Miriam Quick and Jen Christiansen; Source: T1D Index. (www.t1dindex.org) (data)

Why are the number of cases rising?

Scientists still don't fully understand why the number of T1D diagnoses has increased so quickly. Earlier and more accurate detection is certainly part of the story, but the sharp increase in the number of new cases relative to the population hints that underlying indicators of the disease may also be increasing. A number of environmental exposures are associated with increased risk, many of which are related to the health of the gut microbiome. Infections in early life, along with factors associated with pregnancy and childbirth, can cause autoimmune diseases such as T1DM, in which the immune system destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Lifestyle factors may also contribute to this. Obesity and poor diet are well-known factors in the development of type 2 diabetes, and some researchers suspect they may also influence the development of type 1 diabetes.

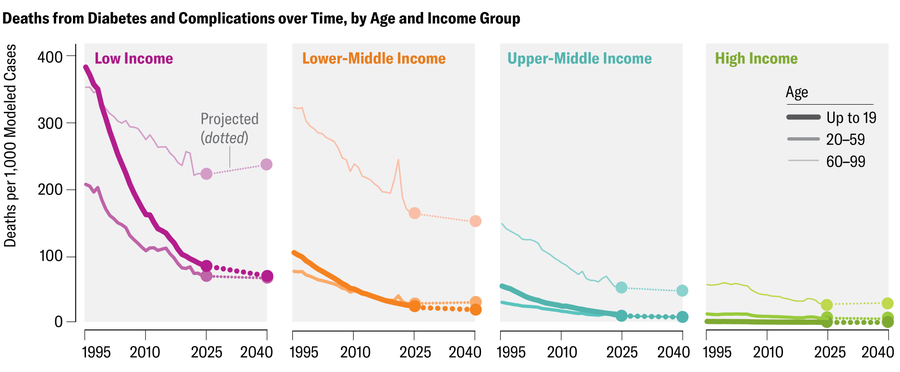

No longer a death sentence

Untreated diabetes can be fatal even for young people. This year, approximately 174,000 people worldwide will die from T1D; about 30,000 of them will be under 25 years of age and will never be formally diagnosed. Many of these deaths are caused by diabetic ketoacidosis, a complication in which ketones build up in the blood, making it more acidic. This condition is often mistaken for something else, leading to delays in intensive care. Children and adolescents with T1D also face an increased risk of long-term complications, including cardiovascular disease and kidney failure. About 30 percent of patients eventually develop end-stage kidney disease.

However, T1DM is highly treatable. Insulin therapy, combined with tools to monitor blood glucose levels, can extend life expectancy and significantly improve quality of life. Where treatment is available, diagnosis is no longer a death sentence, and mortality rates have dropped dramatically as treatment has improved. Global modeling using the T1D Index suggests that if everyone received a timely diagnosis and proper care (and no one died prematurely from diabetes), more than four million more people would be alive today.

Miriam Quick and Jen Christiansen; Source: T1D Index. (www.t1dindex.org) (data)

It's time to stand up for science

If you liked this article, I would like to ask for your support. Scientific American has been a champion of science and industry for 180 years, and now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I was Scientific American I have been a subscriber since I was 12, and it has helped shape my view of the world. Let me know always educates and delights me, instills a sense of awe in front of our vast and beautiful universe. I hope it does the same for you.

If you subscribe to Scientific Americanyou help ensure our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on decisions that threaten laboratories across the US; and that we support both aspiring and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return you receive important news, fascinating podcastsbrilliant infographics, newsletters you can't missmust-watch videos challenging gamesand the world's best scientific articles and reporting. You can even give someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in this mission.