Nick TriggleHealth Correspondent

BBC

BBCThe five-day doctors' strike in England has ended, but it is clear that this dispute – 12 strikes and counting – is far from over.

“We have been let down by Wes Streeting,” says Dr Shivam Sharma, who joined one of the last picket lines of the strike before it ended at 07:00 on Wednesday.

When Labor came to power, it quickly struck a deal with the British Medical Association (BMA), giving them extra money and promising better working conditions.

Doctors took it as a sign that the path to restoring wages to 2008 levels was close, but this would still require another 25% pay rise on top of previous increases, according to the BMA.

“He hasn’t given birth since last year,” says Dr Sharma, who has trained in child and adolescent psychiatry for six years and is a spokesman for the BMA, when asked why the strikes have resumed.

Dr Sharma, who joined other striking doctors outside a hospital in the east London constituency of Streeting, says his years as a resident doctor (the new name for junior doctors) were difficult – harder than they should have been.

In his early years he faced regular rotation in various positions in the West Midlands. “You can be deployed anywhere over large geographic areas. You have little control over your work schedule, people missing weddings and important family events.”

He is taking the exam in September, which will cost him more than £1,000. “This is only one exam. It could cost us tens of thousands of pounds over the course of the training.”

The BMA's position remains that the best way to resolve this dispute is through further wage increases. But with the government absolutely unable to revise pay this year (resident doctors will receive an average 5.4% increase in 2025-26), attention has shifted to issues of non-payment of wages.

During the five days of talks, which ended on Tuesday last week, a range of topics were discussed including exam costs, career progression and the frequency of job rotation, which for some could be every four months.

The BMA wanted to add student loan forgiveness (medical students can rack up debts of £100,000), although the government refused to support this.

“Breath”

Over time, the dispute became bitter when the BMA announced its first strike under Labour.

Streeting accused the BMA of being reckless and showing “total disregard” for patients. In response, the union said it was losing confidence in all the promises made.

Tensions between NHS England and the union flared on Monday as health chiefs criticized the BMA's “tough” approach for blocking requests to allow doctors to return to work to deal with emergencies.

The union responded by accusing the NHS of putting patients at risk by placing too many restrictions on senior doctors covering striking resident doctors.

At times, returning to the negotiating table seemed almost impossible, but since the end of the strike, both sides have shown signs of easing.

Senior BMA sources have spoken of a reluctance to enter into a cycle of strikes and no negotiations, as they did in the final months of the Tory government – there were 11 strikes in 16 months. They mention creating a “breathing space” in the coming days and weeks for further negotiations.

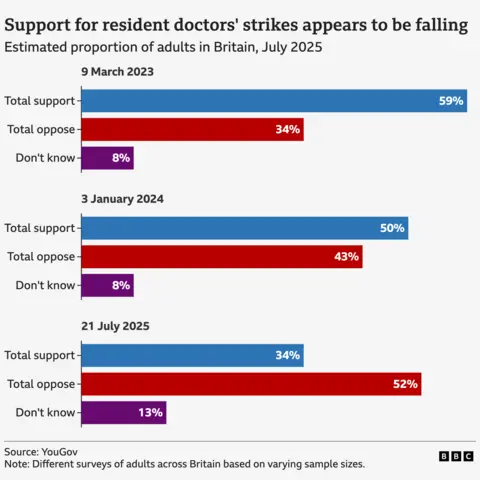

It has also not gone unnoticed by the BMA that public opinion appears to be against resident doctors.

Meanwhile, people close to Streeting stress he wants a deal, although he remains disappointed that the union hasn't at least postponed the strike to allow negotiations to continue.

And in a statement marking the end of the strike, the health minister said: “My door is open to resuming the negotiations we held last week.”

But if they do come to the negotiating table, is there enough common ground to reach an agreement, given that the BMA wants a bigger pay rise and the government is adamant that is not an option?

“It won't be easy,” says Dr Billy Palmer, an NHS workforce expert at the Nuffield Trust think tank. “This controversial situation has a negative impact on both doctors and the NHS as a whole.”

He says that along with pay, retention and wellbeing are “real issues”, but he believes a number of individual changes could collectively have a potentially significant impact.

Besides covering out-of-pocket expenses such as exam fees and making the duty and rotation system less brutal, he has other suggestions.

These include student loan payment holidays so doctors can defer payments without interest and pay them off until they start earning more.

He also mentions the need to address the shortage of specialized jobs that medical residents move into after their first two years of training. More than 30,000 doctors are applying for 10,000 jobs this year, according to the BMA.

In addition, he warns that the government may still have to address one particular pay issue, pointing to an anomaly that means first-year resident doctors earn less than physician assistants.

Will all this be enough to solve this problem? Perhaps, he says, but as with everything in this long-running dispute, there are no guarantees.

Get our top newsletter with all the headlines you need to start your day. Register here.