Prison doulas and legislation can be a lifeline for incarcerated pregnant women. But the most important decision is to completely abolish births in prisons.

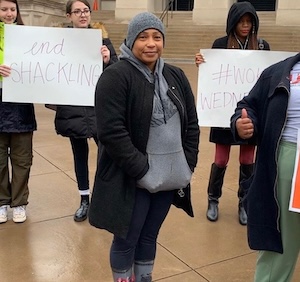

After Autumn Mason began working as a doula during pregnancy and incarceration, she decided to become a prison doula herself and train other women to do the same.

(Courtesy of Autumn Mason)

Autumn Mason was eight months pregnant when she was sentenced to more than two years in prison. “I was in a fog,” she described. “I didn’t even tell my family or partner I was pregnant until… about a month before I was sentenced.” Her lawyer and prosecutors assured Autumn that she would be allowed to remain in St. Paul, Minnesota, with her child under a reduced supervised release order. But the judge overturned the agreement and sentenced Autumn to 32 months in prison. That's when the walls closed in on her. I'm going to give birth to this baby in a prison surrounded by real criminals. she thought to herself. How could I be a mother behind bars?

Luckily, Autumn was wrong about the women she was imprisoned with. They weren't too different from her; they were caregivers who reassured her that she had options to protect her child. One woman suggested that Autumn seek support through the Prison Doula Project in Minnesota. After working with a doula during the birth of her first child, Autumn jumped at the chance to receive the same support and quickly signed up. She had no idea that the experience would change the trajectory of her life after her release from prison, propelling her to become a leading advocate for prison doulas at a time when the number of women incarcerated across the country remained stagnant. alarmingly high and when the black maternal mortality rate keep climbing.

Once you make an appointment with a doula, the matching process can be riddled with delays. Luckily, Autumn was picked up right away due to how far along she was in her pregnancy. Even with the support of a doula, Autumn's final weeks of pregnancy were marred by infrequent doctor visits and one particularly alarming visit to a medical “professional” who had the wrong charts and nearly prescribed Autumn someone else's medicine.

Soon after, Autumn went into labor. “My three roommates were very loving. We were kept indoors where we couldn't have any physical contact with each other,” Autumn recalls. “They broke the rules to…[bring] I need hot towels or drinks, as well as a back and shoulder rub.” As Autumn's contractions began to get closer, she called security to take her to the hospital and she was strip searched before being transported. Even in the hospital, while she was giving birth, two officers hovered over her. “I just remember feeling like an animal in a zoo,” she noted.

Autumn was one of the first women in the state to give birth after Minnesota passed the law. in 2014by abolishing shackles for women in labor. And her Minnesota Prison Doula Project doula was there during her labor and after she was discharged and separated from her newborn. “My doula was able to take photographs of me and my baby that I treasure to this day and that many other women giving birth behind bars don’t get.” However, being separated from her child during those important early years while she served the remainder of her sentence was devastating for Autumn.

Although her experience was far from ideal, Autumn was lucky in many ways. Pamela WynnPregnancy behind bars in Georgia looked very different. During the trial, Pamela's arms and legs were cuffed so tightly that she tripped and fell while entering the transport van. “Two officers picked me up and put me back in the van without checking or asking if I was okay,” Pamela said. After a few days, Pamela's spotting turned into bleeding. As a former registered nurse, she knew something was wrong, but it took weeks to see doctors. When she finally managed to meet with the medical director and the contracting physician, it was suggested as a “professional courtesy” since they had mutual colleagues. Even then, they said they couldn't help her because all decisions were made by the guards and correctional officers.

After sixteen weeks of requests, denials, appeals, and ongoing delays, Pamela was finally allowed to get the care she needed. One evening before her appointment, Pamela felt a rush of warm fluid between her legs, but was unable to see what it was because her cell was dark. “I was hurt and scared,” Pamela recalled. The other female prisoners began knocking and shouting on behalf of Pamela. It was only five hours later that the officer finally opened the door.

In the light of the corridor, Pamela saw that the warm flow she felt was blood. “I was afraid not only for my child, but also for my life.” By the time she arrived at the hospital, Pamela had suffered a miscarriage.

Women prisoners routinely face poor treatment during pregnancy, including inadequate nutrition to support a healthy baby, harmful cavity exams, and childbirth in shackles or solitary confinement. Even though progress has been made in some parts of the country, there is no national standard for the treatment of pregnant women in custody, despite the fact that women fastest growing prison population in America, and most of these women already mothers. Nearly 40 US states have banned the practice of restraining women during childbirth. study interviewing labor and delivery nurses American prisons discovered that many incarcerated patients were shackled Sometimes To all the time. This often occurs due to confusion regarding legislative changes and security guard discretion regarding who is considered a “security risk”. However, mainstream reproductive rights often ignores this aspect of the struggle to achieve reproductive freedom for all.

The odds are stacked against incarcerated pregnant women in a country where it is becoming increasingly difficult for black women to control their destinies and those of their children. Imprisonment only exacerbates this danger. Thanks to her harrowing experiences, Pamela Wynne became known as the “Face of Dignity for Women Prisoners.” After being released from prison in 2013, Pamela founded Restore HER and led successful campaigns such as the adoption HB345 in Georgiawhich prohibits shackling and solitary confinement for pregnant and postpartum women. Likewise, Autumn was inspired to not only become a prison doula herself, but also to train other women to do so. “Just having another person in this room to witness the injustice that they're trying so hard to put us through,” Autumn insists.

Through Project Doula in a Minnesota prisonshe has trained more than 100 prison doulas. Unfortunately, this is still not enough to meet the demand for doulas, and Autumn notes that even as the number of certified doulas increases, many detention centers do not make these services available to those incarcerated there. “We're moving toward more humane birth practices for people involved in the criminal justice system, but it's a slow process,” Autumn says. “Even though we've passed all these pregnancy justice bills in over 25 states, we still get calls all the time about women being shackled during childbirth,” Pamela notes. “We also see stories in the media about women still giving birth alone.”

Some argue that women who want control over their pregnancy experience should simply stay out of the prison system, but this ignores the reality of who incarcerated women are. “Many of them have faced gender-based violence or criminalized poverty,” noted Fatima Goss Graves belonging National Women's Law Center. For example, even though Minnesota created alternative placement program for incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women, Prison Policy Initiative explains that the criminalization of drug addiction, mental illness and poverty has clearly led to the incarceration of women. In addition to the unique way women become ensnared in the criminal legal system, Goss Graves adds, “We're also seeing a lot more examples of people getting pregnant or having miscarriages turned into criminal cases.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

According to new data from Pregnancy Justicein the first two years after the fall Roe v. WadeProsecutors have filed more than 400 criminal cases against women in 16 states related to their pregnancies or pregnancy losses. Goss Graves and her team are very vigilant about these punitive dynamics and work tirelessly to campaign for women's rights, including the protection of women prisoners. In the NWLC's 50-year history, they were one of the first groups to develop a project to study the support women needed when leaving prison. That's why, as part of the recently launched 75 Million CampaignNWCL is sounding the alarm about the 190,000 incarcerated women workers who are so often overlooked. “Whether it's about your ability to support your family and contribute while incarcerated or after you get out of prison, economic and worker protections are also important parts of this conversation,” Goss Graves says.

Black women disproportionately suffer from mass incarceration, financial exploitation, and attacks on bodily autonomy. Prison doulas and legislative efforts to improve prison conditions can be critical links in advocacy. But these are still temporary solutions. Pamela and Autumn agree that the most important solution is to completely abolish births in prison.

Right now Pamela and her team are working on implementation Women's Care Act states across the country that will allow deferred sentencing will promote sentencing alternatives, provide pregnancy testing upon arrest and require improved data collection across the board. The bill has already passed in Colorado and is in the works in California, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, with preliminary talks underway to introduce it in Texas, Illinois and Ohio. “Women don’t have to go to jail or prison if they’re pregnant,” Pamela says.

Autumn is inspired by models from other countries, such as the German “Normality Principle”, where incarcerated parents have access to specialist housing that emphasizes community integration and family contact. In these facilities, mothers can give birth, breastfeed and raise their children while serving their sentences, while working and earning an income that will help them eventually return to their home countries. Similar institutions for mother and child also exist. in the Netherlands And Denmark.

As a storyteller funded and trained through Represent Justice's flagship ambassador programAutumn focuses on portraying honest and compelling storytelling as a vehicle for change. She believes that when we see how our inactions have shaped real people, it makes us want to speak up and do more. “My personal commitment at this time is to create a healing space where families can return and gain the resources and skills they need to live successfully outside the criminal justice system upon release,” Autumn explains. “To give families and children a place where they can come together, love each other and grow together.”