To evaluate technical performance, we first focused on data from the Xenium (10x Genomics) and CosMx SMI (Bruker Spatial Biology) platforms—the two commercial spatial imaging systems with subcellular resolution (50–100 nm) and high-depth multiplexing for RNA and proteins available across all three sites. Using SOPs and protocols from sample preparation to data production, we assessed accuracy, precision, reproducibility, sensitivity and specificity within and between sites. These metrics were evaluated through serial sections from six tissue types (across two conditions: normal and cancerous), using predesigned panels for RNA and protein (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Tables 1–3 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3). The ST dataset profiles more than 8 million cells (with counts ranging from 3,624 to 321,482,112 per sample and a median of 71,296 cells). The ST dataset includes profiles from tissue sections comprising tissue microarrays (TMAs) and whole sections (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2b, Supplementary Table 2 and https://spatialtouchstone.org). Additionally, we curated all PUB spatial imaging data on Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets, accounting for the Xenium, CosMx and MERSCOPE platforms, totaling approximately 33 million cells and approximately 7 billion transcripts. The ST dataset specifically consists of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples including normal (appendix, colon, pancreas and ileum) and cancerous (breast and prostate) tissues. Except for breast cancer samples, which were serially sectioned and profiled in duplicates at a single site (University of Adelaide (UoA)), all other tissue samples in the ST project were serially sectioned at their respective originating institutions. This centralized sectioning approach ensured consistency in techniques and minimized variability that could arise from multiple handling procedures. Samples were subsequently profiled across multiple institutions. To maintain sample integrity and reduce potential degradation, all slides were processed within a 1−3-week window. All samples were analyzed on both Xenium and CosMx imaging-based platforms, generating 77 profiles, and subjected to FFPE single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) (snPATHO-seq, n = 6) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (n = 44) (n = 126 total). The PUB dataset includes both fresh-frozen and FFPE tissue samples from the brain, kidney, lymph node, skin, pancreas, lung, breast, colon, larynx, liver, ovary, prostate, uterus and nerve (n = 177; 131 human and 46 mouse) that have been profiled in Xenium, CosMx or MERSCOPE platforms. Despite the PUB dataset containing a larger number of tissue profiling experiments, samples had fewer cells profiled compared to those from the ST dataset. The STP comprises both the ST and PUB datasets, featuring human cells (n = 22,963,452) and mouse cells (n = 10,572,065) containing both FFPE cells (n = 23,852,502) across 14 different tissue types and fresh-frozen cells (n = 9,693,015) across 3 different tissue types. The STP provides access to approximately 13.833 million cells and a total of approximately 2.3 billion high-quality transcripts (Fig. 1a,b). All graphics within the STP web interface allow users to visualize data comparisons across three categories: ALL (combined PUB and ST), PUB and ST. These options enable detailed cross-comparisons, allowing researchers to probe their sample data against different tissue types or platforms, including Xenium, CosMx and MERSCOPE.

a, Schematic overview of the ST workflow. Tissue samples from normal ileum, appendix, colon and pancreas and from breast (BR) tumors and prostate (PR) tumors were collected for analysis. ST tissue samples were obtained from two independent sites: Site 1 and Site 2. Serial sections from the same FFPE blocks were processed and analyzed using two imaging-based spatial transcriptomics platforms, Xenium and CosMx, across three sites—Site1 (UoA), Site2 (WCM) and Site3 (SJH)—with an additional experimental run at 10x Genomics headquarters (Site 4; 10x Genomics). b, Representation of ST and PUB datasets and tissue types, including breast (BR), brain, pancreas (Panc.), lung, appendix (App.), ileum (Ile.), prostate (Pr.), colon (Col.), lymph node, kidney and skin. c,d, Metrics comparison (normalized TPN and SNR (c), and TPC, TPA, Entropy and MECR (d)) separated by platforms (ST dataset alone) (c) and by tissue and data type (d).

Technical metrics

To establish the technical performance metrics across assays, various parameters were first assessed at the transcript level. The sensitivity of the overall assay was evaluated by comparing the total number of transcripts (transcripts per cell (TPC)) to the total number of targets (Fig. 1d). In the ST dataset, transcript level varied from 0.07 to 0.95 normalized TPC with a mean of 0.29 ± 0.24 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24−0.35) across all tissue types. The PUB dataset, however, recorded up to 2.81 TPC with a mean of 0.82 ± 0.55 (95% CI: 0.72−0.90). Among normal tissues within the ST datasets, pancreas samples exhibited the highest TPC paired with the highest variance (mean of 0.44 ± 0.33 (95% CI: 0.32−0.57)). For ST cancer samples, breast tissue showed the highest mean at 0.33 normalized TPC. In the PUB datasets, pancreas tissue again had the highest mean number of TPC (266), consistent with high overall gene expression20. To ascertain transcript distribution across samples, the total number of transcripts per area (TPA, μm2) was calculated, normalizing the mean number of transcripts in a given cell area to the target gene panel size. The ST dataset TPA average was 1.4 ± 0.72 (95% CI: 1.22−1.55), peaking at 3.4 TPA, whereas the PUB dataset TPA average was 0.5 ± 0.60 (95% CI: 0.41−0.61), peaking at 1.8 TPA.

Cell size and cell segmentation can significantly impact these above metrics; therefore, normalized transcripts per nucleus (TPN) calculations were introduced to account for signals within the nucleus, independent of cell segmentation (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2). TPN is calculated by dividing the observed number of transcripts within nuclei by the number of cells. An average TPN of 20 indicates that 20 transcripts were detected within the nuclei segmentation mask of a given imaging-based platform. The ST dataset showed a TPN range from 18 to 257, with an average of 73 ± 52.86 (95% CI: 61.02−85.01), whereas the PUB datasets ranged from 3.4 to 779, with an average of 91.43 ± 100 (95% CI: 75−108). Notably, high TPN, TPC and TPA values in the PUB dataset were primarily driven by a single sample with whole-transcriptome profiling, which highlights the ability of these metrics to find outlier samples.

The variability in metrics such as TPC, TPA and TPN is influenced by the choice of imaging-based platform used for the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Within the ST dataset, which consists of serial sections and likely exhibits less variability than the PUB dataset, the CosMx platform demonstrated higher TPN (108.6 ± 60.9 (95% CI: 87.71−129.61)) and TPA (mean = 1.93 ± 0.66 (95% CI: 1.70−2.16)), whereas the Xenium platform showed superior TPC (mean = 0.4 ± 0.28 (95% CI: 0.30−0.48)). In the PUB dataset, MERSCOPE showed a normalized TPC (0.12 ± 1.66 (95% CI: 0.56−0.81)) and TPA (1.88 ± 2.96 (95% CI: 0.2−5.42)).

Variations in tissue size—from large sections to partial sections and TMAs—and differences in tissue type, such as healthy versus diseased states (for example, normal versus cancerous tissues and non-infected versus infected tissues), are both critical factors influencing the number of detectable transcripts and cell counts in spatial transcriptomics. For example, smaller tissue sections or TMAs, which are often used for high-throughput or targeted analyses, may yield fewer total detectable transcripts and lower cell counts due to the constrained sample size and limited area for capturing cellular and molecular heterogeneity.

These factors highlight the critical importance of both tissue size and type when designing spatial transcriptomics experiments, and careful consideration of these variables is essential to ensure the robustness, accuracy and interpretability of the resulting data, as each contributes uniquely to the challenges and opportunities in spatial transcriptomics analyses.

A notable example of how sample type and size impact data outcomes is evident in a large COVID lung study within the ST dataset, which predominantly used TMA cores from biopsied patients. These cores recorded the lowest overall cell counts (mean = 1,117.2 ± 598.01 (95% CI: 617.3−1,617.2)), likely due to the constrained sample size and specific pathological conditions of the tissue, affecting cell integrity and transcript detection efficiency. This highlights the crucial role of sample selection and preparation in spatial transcriptomics, which substantially influences the robustness and interpretability of the resulting data, highly affected by the selected field of view (FOV) and surface area.

Probe specificity was then evaluated using the ‘specificityFDR’ metric, where a value of 0.05 indicates that, on average, 5% of transcripts per gene are false positives. Our results show that, generally, lower specificityFDR values corresponded to higher experiment or sample quality. In the ST dataset, specificityFDR values ranged from 5.5 × 10−5 to 0.069 (mean = 0.05 ± 0.02 (95% CI: 0.41−0.49)), whereas, in the PUB dataset, values ranged from 8.2 × 10−5 to 0.69 (mean = 0.23 ± 0.21 (95% CI: 0.19−0.26)) (Supplementary Fig. 2), notably highlighting a very broad error range for public datasets.

Next, sample noise levels were evaluated using the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and dynamic range. The SNR measures the distribution of mean transcript detection versus mean control probes, assessing the extent to which transcripts are detected above noise levels. The SNR for the ST dataset ranged from 0.12 to 0.53 (mean = 0.28 ± 0.08 (95% CI: 0.26−0.30)), and the PUB dataset ranged from 0.01 to 0.90 (mean = 0.33 ± 0.19 (95% CI: 0.30−0.36)) (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Dynamic range reflects the range of expression, with a dynamic range of 3 representing a thousand-fold increase in expression between the largest average of every gene compared to the average of negative control probes; higher values indicate less noise. The dynamic range for the ST dataset ranged from 2.14 to 5.85 (mean = 4.11 ± 1.03 (95% CI: 3.88−4.35)) and ranged from 1.13 to 5.06 (mean = 2.87 ± 1.25 (95% CI: 2.66−3.07)) for the PUB dataset (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Notably, the PUB dataset exhibited a narrower overall range for these metrics, whereas the ST dataset showed lower variance, suggesting greater stability across different tissues and assays. Tissue-specific trends were also observed: the highest SNR in the ST dataset was recorded in breast tissue (mean = 0.37 ± 0.11 (95% CI: 0.27−0.46)), whereas the highest SNR in the PUB dataset was recorded in brain tissue (mean = 0.51 ± 0.23 (95% CI: 0.43−0.59)). For dynamic range, both datasets showed the highest values in pancreas samples (ST: mean = 4.68 ± 0.86, 95% CI: 4.35−5.02; PUB: mean = 4.61 ± 0.44, 95% CI: 2.65−3.01). Variability in SNR and dynamic range was tissue dependent within the ST dataset, with normal tissues such as the appendix showing a narrower range (SNR = 0.11−0.37; dynamic range = 2.14−4.75) compared to cancerous tissues such as breast cancer (SNR = 0.22−0.52; dynamic range = 2.70−5.15). The fraction of transcripts assigned to cells (FTC) was calculated to determine the percentage of transcripts accounted for across the tissue sample after cell segmentation. For instance, an FTC value of 0.8 indicates that 80% of the total transcripts present in the sample are assigned to cells. The FTC for the ST dataset ranged from 0.20 to 1.0 (mean = 0.85 ± 0.20 (95% CI: 0.81−0.90)), whereas, for the PUB dataset, it ranged from 0.02 to 1.0 (mean = 0.87 ± 0.15 (95% CI: 0.85−0.90)) (Supplementary Fig. 3c). These results suggest that the FTC was consistent across datasets. As the STP continues to grow with user-generated datasets, the scale and robustness of spatial transcriptomics will improve, potentially leading to more consistent SNR, dynamic range and FTC values across a wider variety of tissue types and conditions.

The mutually exclusive correlation ratio (MECR) measures the quality of cell segmentation by assessing the rate at which co-expressed genes, which should be exclusive to a specific cell type, are expressed together9. Using a series of marker genes in pairs of cell types, MECR measures how often these genes are co-expressed above a threshold of zero transcripts in the same assigned cell. Of note, this metric, primarily focused on general immuno-oncology profiling, indicates greater specificity of transcript discrimination with lower values. For example, an MECR value of 0.01 indicates that, on average, 1% of all cells co-express genes that should be mutually exclusive. The MECR for the ST dataset ranged from 0.02 to 0.12 (mean = 0.05 ± 0.02 (95% CI: 0.05−0.06)), whereas it ranged from 0.01 to 0.96 (mean = 0.13 ± 0.18 (95% CI: 0.10−0.16)) for the PUB dataset (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3c). Notably, the variability of MECR was higher in the PUB dataset, likely due to differences in tissue types examined, assay consistency, platforms used and procedural variations across different sites. In terms of sample type, MECR variability was more pronounced in normal samples than in cancer samples, with normal sample values ranging from 0.01 to 0.16 (mean = 0.06 ± 0.04 (95% CI: 0.055−0.071)) compared to 0.01 to 0.10 (mean = 0.04 ± 0.02 (95% CI: 0.035−0.046)) for cancer samples. MECR performance also varies with cancer type; it was more effective in breast cancer samples (range, 0.034−0.047) compared to prostate cancer samples (range, 0.028−0.059), where the presence of more infiltrating normal cells could impact the metric (see the ‘Biological quality metrics’ subsection).

We then examined several other key metrics for assessing samples. First, the ‘sparsity’ value is a measurement of how empty the gene expression matrix is across the gene panel, providing insights into the overall coverage of the target panel in the tissue type used. A sparsity value of 0 indicates that 100% of the matrix contains expressed genes, whereas a value of 0.9 means that 10% of the queried genes are quantified from a sample. For the ST dataset, sparsity values ranged from 0.90 to 0.96 (mean = 0.94 ± 0.01 (95% CI: 0.93−0.94)), whereas, in the PUB dataset (Supplementary Fig. 3c), they ranged from 0.62 to 0.98 (mean = 0.86 ± 0.06 (95% CI: 0.85−0.87)).

Second, we defined the ‘entropy’ value, which quantifies uncertainty or randomness in gene expression, with higher values indicating greater variability and lower predictability. For the ST dataset, entropy values ranged from 0.30 to 0.68 (mean = 0.46 ± 0.08 (95% CI: 0.44−0.48)), whereas, in the PUB dataset, they ranged from 0.17 to 2.31 (mean = 0.88 ± 0.38 (95% CI: 0.82−0.95)) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Third, we quantified ‘complexity’ as a measurement of how many genes account for explaining 50% of total counts in the sample, such that a complexity value of 30 means that 30 genes are responsible for half of all the transcripts in the sample. Notably, a normalization by panel size makes the complexity metric (‘normComplexity’) comparable betweeen platforms with high variance in panel size. normComplexity metrics for the ST dataset ranged from 0.09 to 0.77 (mean = 0.5 ± 0.15 (95% CI: 0.46−0.53)), whereas, within the PUB dataset (Supplementary Fig. 3c), they ranged from 0.39 to 3.46 (mean = 0.63 ± 0.48 (95% CI: 0.55−0.71)). This metric was comparable across different tissue types within ST, except for pancreas, which had a minimum normComplexity range of 0.09 compared to all other tissue types (minimum range of 0.39).

Furthermore, the complexity and entropy metrics were influenced by the platform used. This is related to previous observation that Xenium has higher TPN despite the high SNR (Fig. 1c,d). For the ST samples analyzed with the CosMx platform, complexity and entropy values were consistently higher than those processed on the Xenium platform, specifically with these probe sets. Specifically, normComplexity values ranged from 0.49 to 0.77 (mean = 0.63 ± 0.10 (95% CI: 0.60−0.67)) on CosMx and from 0.09 to 0.49 (mean = 0.39 ± 0.09 (95% CI: 0.36−0.41)) on Xenium.

Reproducibility metrics

To perform a comprehensive analysis of reproducibility across both ST and PUB datasets, we scaled all technical metrics for each sample and conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The results indicated that the imaging-based platform used was the largest determinant in differentiating the principal components, not the samples or datasets themselves. Specifically, the Xenium and CosMx samples were distinctly separated by principal component 1 (PC1), which accounted for 34.39% of the total explained variance. Additionally, an outlier was identified in the PUB dataset, which, upon further examination, was attributed to a limited selection of FOVs for the CosMx platform. A comparison of cell counts across each tissue type revealed significant variability between standard H&E counts and those from both imaging platforms. Although there are differences in cell segmentation algorithms, resulting in varying cell counts, the ability of the platforms to detect broad cell types remains largely unaffected. This consistency is particularly evident because many of these signals concentrate in the nuclear area (Fig. 2c,d). H&E staining generally provides a more accurate cell count because it does not depend on various combinations of cell membrane segmentation markers. We found the cell counts through cell segmentation to be consistent between H&E and Xenium, whereas CosMx cell counts were consistent with the other platforms depending on the tissue type. For example, we observed the number of cells in prostate tissues to be consistent across technology with, on average, 86,588 cells from H&E, 100,794 cells from Xenium and 97,209 cells from CosMx. This variability underscores the importance of careful interpretation of any metrics derived from imaging-based spatial transcriptomics platforms, as they heavily rely on the accuracy of the cell membrane markers (Supplementary Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 5).

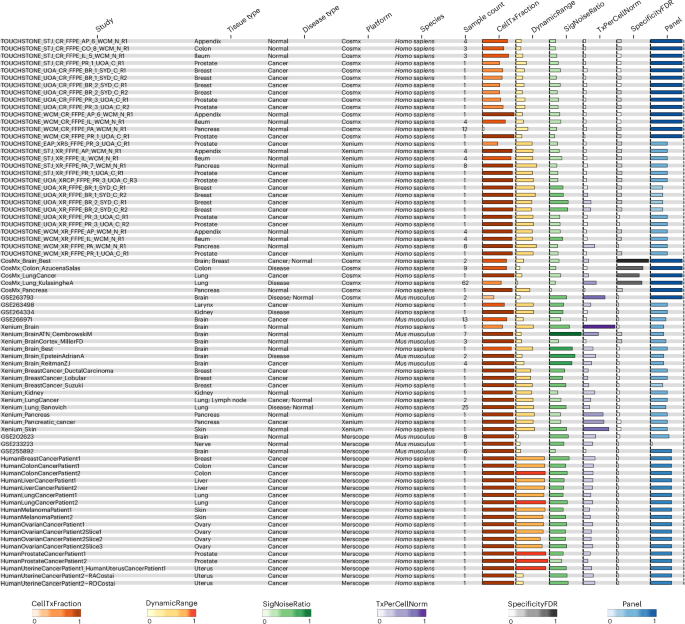

All metrics for ST and PUB datasets are shown, which represent all conditions (normal, cancer and disease) and species (Homo sapiens and Mus musculus). Metrics include fraction of Tx per cell (CellTxFraction; orange), DynamicRange (yellow), SNR (SigNoiseRatio; green), TxPerCellNorm (purple), specificityFDR (gray) and Panel size (dark blue). FDR, false discovery rate; Norm, normalized; Tx, transcripts.

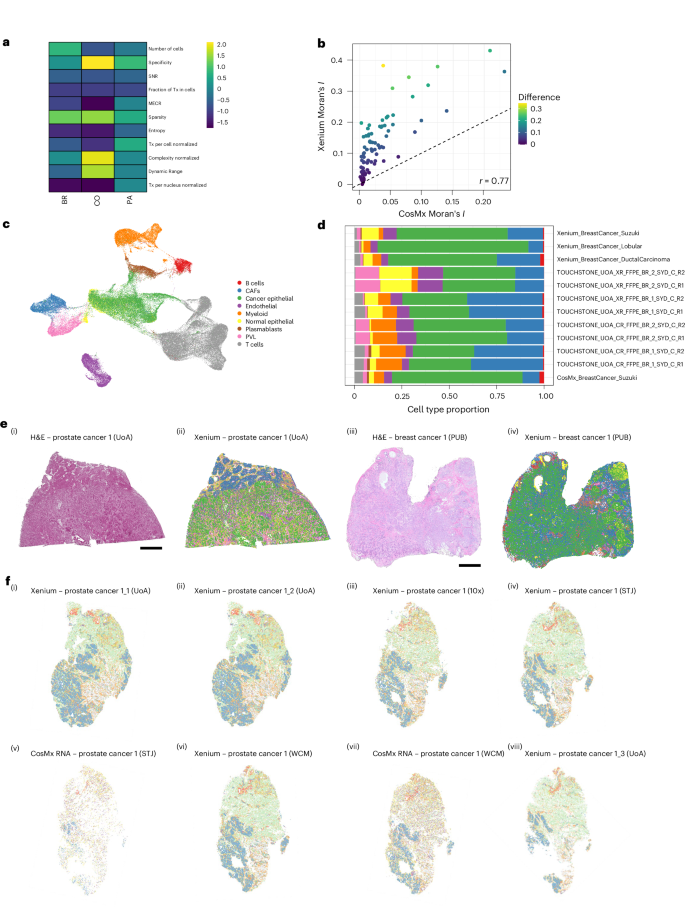

The ST project provided a unique opportunity to delve deeper into reproducibility between the same tissue type (in this case, breast cancer) from different studies and datasets (ST and PUB) across imaging-based transcriptomics platforms (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Figs. 3d,e and 4). A total of six breast cancer samples were used for comparison: four sequential sections from two samples in the ST dataset (profiled in duplicates, with two sections from two samples on Xenium and two sections from two samples on CosMx) and four samples from the PUB dataset (three on Xenium and one on CosMx). For the ST samples, a total of 3,016,015 cells were detected across all spatial profiles, with an average of 377,000 ± 83,807 cells per section (95% CI: 306,937−447,066). By contrast, the PUB samples had a total of 1,393,890 cells across all spatial profiles, with an average of 348,472 ± 213,783 (95% CI: 8,295−688,649) cells per section profiled. Although the average number of cells profiled was similar between the two groups, more PUB samples were processed on the Xenium platform than on CosMx.

The FTC for the ST dataset ranged from 0.20 to 1.0 (mean = 0.85 ± 0.20 (95% CI: 0.80−0.90)), whereas it ranged from 0.02 to 1.0 (mean = 0.87 ± 0.15 (95% CI: 0.85−0.90)) for the PUB dataset. The mean FTC for the ST dataset is likely more representative of metrics commonly observed by general users. The specificityFDR for the ST dataset ranged from 0.045 to 0.060 (mean = 0.05 ± 0.02 (95% CI: 0.041−0.048)), and it ranged from 8.24 × 10−5 to 0.7 (mean = 0.23 ± 0.21 (95% CI: 0.19−0.26)) for the PUB dataset. These values indicate that the specificityFDR was similar across breast tissue for both datasets (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The variance in entropy was much higher for the PUB dataset, ranging from 0.58 to 1.03 (mean = 0.75 ± 0.2 (95% CI: 0.43−1.05)) compared to the ST dataset, which ranged from 0.40 to 0.68 (mean = 0.55 ± 0.1 (95% CI: 0.46−0.62)), showing lower variability (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

To establish the variability across the data, spatial autocorrelation was calculated for every sample using Moran’s I statistic21. Only the common genes between the two platforms and all samples (n = 203) were selected (Fig. 3). The mean Moran’s I scores were 0.080 and 0.144 for ST and PUB datasets, respectively (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 3d,e). The standardized effect size for each metric across ST and PUB datasets is shown (Supplementary Fig. 3a) to understand the technical variability between cohorts and tissue types profiled in both. These observations highlight the reproducibility and consistency of metrics in spatial transcriptomics, which likely result from more controlled sampling and experimental design in the ST dataset. Overall, the ST breast cancer dataset demonstrated greater consistency across all metrics compared to the PUB breast dataset, yet their mean values remained similar (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3c). This underscores the necessity of comprehensive technical evaluations to assess the accuracy of experimental assays. Overall, although the metrics exhibit platform-dependent variability, they remain relatively stable overall, with the ST dataset exhibiting greater uniformity than the PUB dataset. This underscores the value of SOPs within the STSOP framework (Supplementary Fig. 3a,c).

This unique experimental design allowed us to evaluate the reproducibility of these assays. Serial sections sequentially processed within the same institute highlight the consistency of both Xenium and CosMx platforms. Data from both prostate (n = 1) and breast (n = 2) tumors had negligible variation in mean transcript quantifications across the entire range of detection (r = 1.00, n = 3 total) (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 12a). Adjacent tissue sections, shipped and processed at independent sites, yielded highly consistent data, with correlation coefficients typically exceeding 0.95 (mean r = 0.97) (Supplementary Fig. 12b,c).

a, Standardized effect size difference of technical metrics between tissue types present in ST and PUB datasets. b, Scatter plot of autocorrelation (Moran’s I) for all breast cancer samples present in ST and PUB datasets for the Xenium and CosMx platforms. c, UMAP representation of reference scRNA breast cancer used for cell type annotation of spatial datasets40. Each cell is color coded based on its type. d, Variations in cell type proportions across different breast cancer samples. e, Comparative visualization of H&E with scale bar, 2,000 µm, and Xenium (XR) cluster plots for breast tissues in both ST and PUB datasets using cell type annotation from the same reference (using color code from c and d). (i) H&E image of an ST breast cancer sample profiled at Site 1 (UoA). (ii) Cell type plot of an ST breast cancer sample profiled at Site 1. (iii) H&E image of a PUB breast cancer tissue. (iv) Cell type plot of a PUB breast cancer tissue. f, Cell type plots from cell annotation transfer from snPATHO-seq reference for a prostate cancer sample tissue profiled on both XR and CosMx (CR) platforms across different sites. (i–iii) Prostate sample from Site 1, analyzed with XR at 10x Genomics headquarters, Site 2 (WCM) and Site 3 (STJ), respectively. (iv) Prostate sample from Site 1, profiled with CR RNA at Site 2. (v) and (vi) Prostate sample from Site 1, profiled with XR at Site 1. (vii) Sample from Site 1, profiled first with XR and then followed by CR Protein (same section); dual assay conducted at Site 1. (viii) Sample from Site 1, analyzed with CR at Site 3. BR, breast cancer; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CO, colon; PA, pancreas; PVL, perivascular-like.

To further validate the biological relevance of these metrics, we referenced snPATHO-seq data from the prostate samples as a cell-specific benchmark (Fig. 3) and annotated cell types for all 12 assays. Our analysis confirmed that 100% of cell types (n = 12) identified in the reference dataset were represented in all assays, with very similar proportions (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 5). This consistency in cell type identification across assays underscores the accuracy and utility of the ST dataset in capturing the cellular landscapes of tissues, exemplified here by prostate cancer.

Biological quality metrics

To evaluate the accuracy of transcript quantifications from ST platforms, we performed snRNA-seq (snPATHO-seq; Methods) from all the FFPE tissue assessed in this study (Supplementary Fig. 6). Although the snPATHO-seq quantifications are not considered an absolute ground truth, the technology has proven effective in providing robust transcript detection across a broad dynamic range22,23. The isolation of individual cells or nuclei also provides relatively pure reference expression profiles for the cell types assessed, which is crucial for evaluating the extent of segmentation error that can result in mixed transcript profiles.

Several criteria were used to assess the accuracy of ST platforms. Initially, the average transcript abundance for each gene between the snPATHO-seq and ST data for each tissue was compared. Xenium samples consistently showed good correlation (Spearman’s ρ = 0.78, r = 0.64–0.94) with snPATHO-seq data across its entire dynamic range (Fig. 3a,b). By contrast, CosMx samples had lower correlation (Spearman’s ρ = 0.60, r = 0.35–0.80) and displayed ubiquitously inflated detection of lowly expressed genes and variably reduced sensitivity for highly abundant transcripts (Fig. 3a,b), aligning with previously noted variation in dynamic range (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

However, comparing mean expression across a tissue can be misleading because although noise tends to distribute evenly throughout the tissue, marker transcripts for rare cell types may be highly abundant in individual cells and yet have low mean counts across the tissue. To address this, the consistency of detected expression profiles within individual cell types was evaluated using matched snPATHO-seq data as a reference for supervised cell type annotation using InSituType24. Further supporting the reproducibility of these platforms, we note that replicate samples frequently exhibit similar cell type proportions with these predictions (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). The correlation of cell type expression patterns was consistent with those of the bulk tissue. Xenium performed consistently well with a mean cell type correlation coefficient of 0.78 (r = 0.48–0.95). Although some CosMx samples, such as breast cancer sample 2 (BR_2: replicate 1, Spearman’s ρ = 0.80; replicate 2, Spearman’s ρ = 0.76), correlated reasonably well, the variability across samples was notably higher (mean = 0.57, r = 0.25–0.80) (Fig. 3b).

Cell segmentation poses another major challenge that impacts the accuracy of transcript quantifications—imprecise cell boundaries can lead to transcript misassignment from adjacent cells, producing ‘mixed’ transcriptomic profiles. Although metrics such as MECR can detect co-detection of mutually exclusive transcripts, they do not fully account for transcript misassignment, which can distort detected expression. To better understand the impact of segmentation errors, each cell was treated as a mix of pure cell types, and their profiles were decomposed using robust cell type decomposition (RCTD)25 with the snPATHO-seq data as a reference. This approach revealed that deconvolution weights are sensitive to any factor negatively affecting the correlation of the ST quantifications with the cell type reference. In samples with high levels of noise, these weights may not solely reflect segmentation error (Fig. 3c).

The comparison of Xenium data with snPATHO-seq also provided insights into the impact of the different segmentation strategies on the accuracy of transcriptional profiles. The prostate cancer sample was also subjected to Xenium In Situ Gene Expression (Human Multi-Tissue and Cancer Panel) with cell segmentation staining-based nuclear (DAPI), cytoplasmic (18S rRNA, αSMA/vimentin) and membrane (TP1A1/E-cadherin/CD45) staining. For this sample, three segmentation approaches were compared: nuclear expansion at varying distances, staining-based morphology segmentation and Proseg26, which infers plausible cell boundaries based on the spatial distribution of transcripts.

As anticipated, TPC increased as a function of nuclear expansion distance (Fig. 3d). However, increased expansion distances can result in transcript misassignment, as evidenced by elevated MECR values and decreased cell type purity after cell type decomposition (Fig. 3d). Tissue stroma is particularly problematic as it comprises diverse cell types—for example, fibroblast transcripts often contaminated annotated immune cells (Fig. 3e). Despite these challenges, the extent of transcript misassignment suggested by cell type decomposition remains modest: if we assume that decomposition weights purely reflect transcript assignment due to segmentation, the median extent of error (1 − dominant annotation weight) is only 14% for the common 15-µm expansion for Xenium data. Cell type annotation is also robust against these errors, producing effectively identical annotations for all segmentation strategies (Supplementary Fig. 7). Nuclear segmentation alone provided higher cell type purity but at the cost of a dramatic reduction in transcript assignment (43.3 versus 81.6 TPC with 5-µm expansion). The staining-based morphology segmentation, or ‘multimodal’ approach, struck a balance by producing high-purity profiles while retaining higher TPC (74.6 per cell) (Fig. 3d).

Proseg demonstrated that high-quality segmentation could be performed without reliance on staining strategies to detect cellular compartments. Proseg uses cell simulation to infer morphologically plausible cell boundaries based on the localization of cell transcripts. Its segmentation resulted in the highest purity (MECR: 0.029; median maximum decomposition weight: 0.97) and 1.7× more TPC than multimodal segmentation (128.3 versus 74.6) (Fig. 3d). Clustering the resulting expression profiles also produced clusters that were more distinct than those from other segmentation approaches, with the highest mean silhouette width and cluster neighborhood purity (Fig. 3f). Although clustered data from each segmentation approach reasonably reflected cell type annotations, Proseg proved ideal for data where cell typing is performed by clustering rather than label transfer approaches. Together, this supports that segmentation approaches informed by regional transcript patterns may ultimately outperform those based on protein stains and morphological heuristics, such as nuclear expansion.

Poor sensitivity impairs granular interrogation of cellular and tissue organization

The ability to extract biological insight from spatial transcriptomics data is majorly influenced by the technical performance of the platforms used and preparation methods. To investigate this, we evaluated the ability of these platforms to perform several common tasks across datasets with varying quality characteristics. Specifically, we assessed the detection of diverse cell types throughout tissues, determined the extent to which both coarse and fine tissue organization can be resolved and evaluated the potential to predict intercellular signaling based on localized expression of ligands and their cognate receptors.

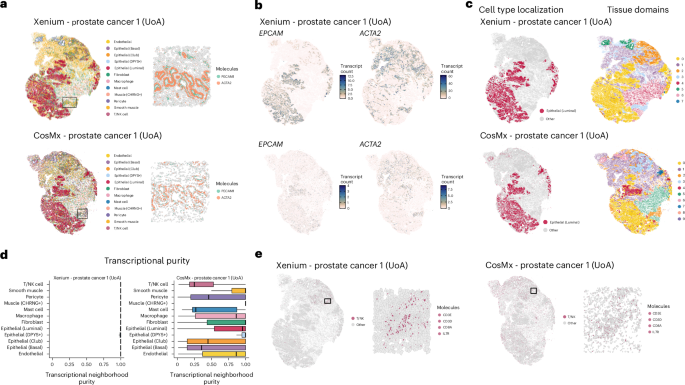

For coarse cell typing, which minimally requires confident detection of cell-type-specific marker transcripts, it is plausible to assume that this task can tolerate some level of noise from off-target probe hybridization and segmentation error, provided that the dynamic range of marker transcripts is sufficiently high27,28. Our initial analysis focused on cell type marker detection within tissue structures with well-defined cellular organization. This included histologically confirmed blood vessels in a prostate adenocarcinoma sample, the mucosa of the appendix and the interface of malignant cells with healthy hepatocytes in a metastatic breast cancer sample (Supplementary Fig. 8). The high sensitivity of the Xenium platform facilitated robust transcript detection of all marker genes assessed, clearly demarcating relevant tissue structures (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). Despite lower sensitivity in the CosMx data, highly expressed genes such as ACTA2 in fibroblasts from prostate tumors and APOC1 in hepatocytes from breast cancer metastasis still resolved tissue structure. Cell types defined by markers with inherently lower expression, such as LGR5 in intestinal stem cells or PECAM1 in endothelial cells, were not clearly identifiable (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9).

a, Left: visualization of tissue structure from adjacent prostate tumor samples with each cell type uniquely colored by technology (Xenium and CosMx). This provides a direct view of the cellular composition and spatial organization within the tissue. Right: expression of PECAM1 (endothelial) and ACTA2 (smooth muscle) in a region with defined blood vessels (marked by black box on left). Each colored point corresponds to an individual transcript. b, Abundance of cell-type-specific transcripts (ACTA2, smooth muscle; EPCAM, epithelial). Each point reflects an individual cell, colored by transcript abundance. c, Left: localization of annotated luminal epithelial cells. Right: tissue domains identified by BANKSY. Spatial clustering was performed independently on each sample. d, Purity of annotated cells in gene expression (principal component) space. e, Localization of annotated T/NK cells (left, tissue plots) and T/NK-specific transcripts (right, cropped regions). T/NK cell, T/natural killer cell.

We demonstrated that data of varying quality can yield similar proportions of predicted cell types using automated annotation methods but that the correlation of annotated cells with single-cell nuclei sequencing references can vary (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Generally, these annotations capture similar high-level tissue organization across all datasets despite quality differences (Supplementary Figs. 6–10). Major cell types are annotated in similar tissue areas of the tissue, and tissue domains are identified using spatial clustering methods (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 10). To further explore whether technical variation introduces more subtle errors in cell type annotation, we quantified the purity of cell type annotations within neighborhoods of the PCA embedding from transcript quantifications. Accurately annotated cells of a given type are assumed to have a high degree of transcriptional similarity, whereas ambiguous annotations will not be transcriptionally distinct from other cell types. The average neighborhood purity correlated directly with quality metrics, indicating that these metrics influence the ability to distinctly resolve expected cell types from the reference annotations (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 10c). For instance, various cell types, such as lymphocytes, consistently exhibit lower purity in CosMx samples. This suggests that these annotated cells are not transcriptionally consistent, potentially indicating misannotation and needed improvements. This issue was apparent in the prostate tumor samples analyzed with CosMx, where annotated T/natural killer cells were diffusely distributed throughout the tissue but lacked the sensitive detection of marker transcripts observed in the Xenium samples of the same tissue (Fig. 4e). However, this reduced purity may also reflect the ability of the platform to capture heterogeneous cell types and detect diverse cellular states, characterized by an increased diversity of transcripts, even if it compromises sensitivity.

Multi-omic profiling assessment: single cell to spatial, transcriptome to proteome

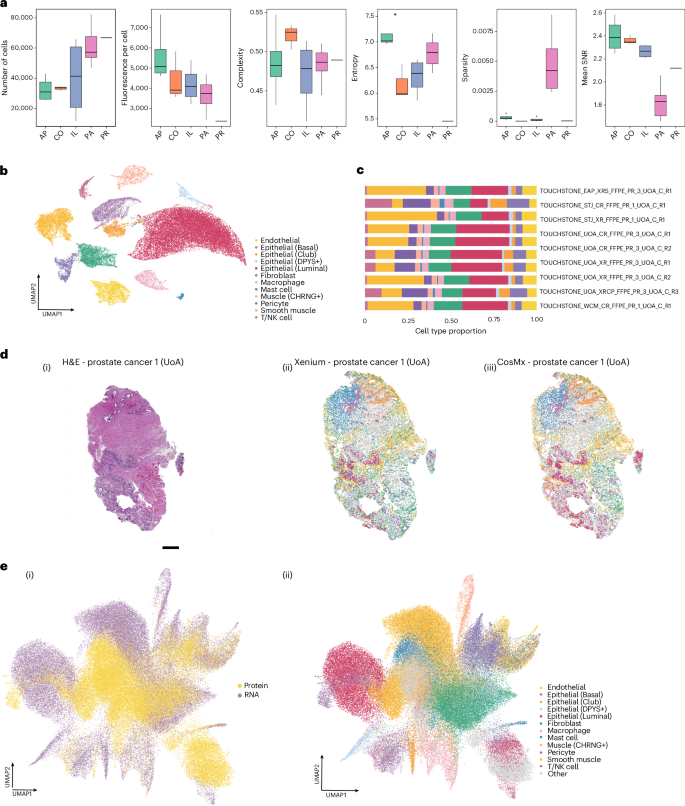

We next sought to address an important unanswered question in the field: ‘How does spatial transcriptomics correlate with spatial proteomics?’ For this analysis, the Human Multi-Tissue and Cancer Panel (377-plex, Xenium) was used for transcriptomics, and the Human Immuno-Oncology Panel (64-plex, CosMx) was used for proteomics. Like our approach in transcriptomics, technical metrics were derived to assess multi-omic features from RNA to protein. For this study, a total of 24 samples were used, comprising 23 normal tissues and one cancerous tissue. The tissue types for the ST multi-omics dataset included four appendix samples, three colon samples, four ileum samples, 12 pancreas samples and one prostate cancer sample. For the statistical measurements, we assessed total nuclei count (TNC), fluorescence per cell (FPC), complexity, entropy, sparsity and SNR (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 11).

a, Technical metrics comparison across different tissues for CosMx protein samples, with boxes color coded by tissue type: appendix (AP), green; colon (CO), orange; ileum (IL), blue; pancreas (PA), pink; prostate (PR). b, UMAP representation of cell type annotation for single-cell prostate cancer (Leiden clustering, resolution = 1, number of neighbors = 30, number of components = 30) with each cell colored according to its type. c, Analysis of the differences in cell type proportions across different sections of the prostate cancer sample, conducted across multiple sites; each bar represents an individual dataset that was cell phenotyped using the same reference snPATHO-seq PR sample. d, Visual comparison of the same sample: H&E image on the left with scale bar 500 µm; the cluster plot from the Xenium RNA sample in the middle; and the cluster plot from the CosMx Protein sample using Leiden clustering (resolution = 1, number of neighbors = 30, number of components = 50) on the right. All cell type color codes are from b and c. e, UMAP representations of both the Xenium RNA and the CosMx Protein profiles, examining batch effects (left) and differences in clustering/cell annotations (right).

Although TNC is not a direct measurement of sample quality, it can be a quick and useful metric to assess sample representation. However, the other metrics demonstrate more accurately sample quality. For spatial proteomic profiling, TNC ranged almost eight-fold, from 11,661 to 82,123 (mean = 49,579.58, s.d. = 18,764.04). Similar to spatial transcriptomics, TNC was most dependent on nuclei identification, tissue and FOV size, with TMAs having smaller TNC than whole sections. We then used FPC to measure the efficiency of antibodiesʼ ability to bind to cells across all markers, leveraging the total unfiltered fluorescence expressed within each cell. In the ST dataset, FPC ranged from 2,379 to 7,649 (mean = 4,109 ± 1,188). The FPC varied with tissue type; differences were observed among colon (mean = 4,440, s.d. = 1,212), ileum (mean = 4,204, s.d. = 952), pancreas (mean = 3,641, s.d. = 740) and prostate (2,379). Low values for this metric may indicate a lower expression level of the target fluorescent marker in the cells of that tissue type, which is useful for highlighting targets that might require orthogonal methods of quantification, differential labeling or tissues with unusual density profiles (Fig. 5a).

Spatial multi-omics integration: RNA into protein

The multi-omics integrative analysis to interrogate RNA and protein was conducted in two distinct stages. Initially, cell phenotyping was performed using the in situ RNA spatial transcriptomics breast cancer sample with corresponding reference data obtained via snPATHO-seq (Fig. 5b,c). Concurrently, the same tissue sample analyzed for protein expression using the CosMx platform was subjected to normalization using a centered log-ratio approach, and cells exhibiting low expression across all proteins (n = 62) were systematically filtered out (Fig. 5b).

After normalization, PCA was performed on the top 50 principal components, with those 50 principal components used to calculate the relationships between cells, setting the number of neighbors at 30. Subsequently, cells were clustered using the Leiden algorithm with a resolution of 0.5, resulting in the identification of 17 distinct clusters. To integrate both modalities, MaxFuse, a method that leverages corresponding and weakly linked features from each modality, was used. Of the features identified, 27 corresponding to both RNA and protein were retained and used for integration analysis. Throughout the model training stage, labels previously established for each modality (cell annotation RNA and Leiden cluster protein) were used to maintain an agnostic perspective and prevent overfitting, particularly by avoiding reliance on unverified protein annotations. The integration results revealed a significant overlap between RNA and protein modalities in the derived embedded space (Fig. 5d). Notably, smooth muscle cells were overrepresented in the RNA data (Fig. 5e), whereas epithelial cell types showed good alignment across multiple clusters originating from the protein modality. This alignment suggests that these cell types were successfully profiled in both assays and can be distinctly identified through clustering. Based on these findings, we propose a downstream approach for cell annotation that uses this joint embedding, which annotates cells within a shared space between RNA and protein, notably enhancing the accuracy and tracing of cell type identification and localization (Fig. 5b–e).

Although spatial transcriptomics has the capacity to profile a larger array of genes, proteomic profiling remains a valuable orthogonal method for validation, capable of resolving several cell types independently. This dual approach underscores the complementary nature of RNA and protein analyses in enhancing the understanding of cellular functions and interactions within complex tissue environments.