November 14, 2025

2 minute read

Scientists have discovered a mysterious meteorite crater in China

Thousands of years ago, a space rock fell into what is now China, leaving behind a bowl-shaped crater about 900 meters wide.

Scientists have discovered a huge crater from an asteroid impact in China. The bowl-shaped depression is about 900 meters wide, more than eight times the length of a football field.

IN paper In a paper published last month, the researchers behind the discovery said the structure, dubbed Jinlin Crater, was likely formed by a meteorite impact during the early to mid-Holocene, a geological era that began just 12,000 years ago. The results were published October 15 in the journal. Matter and radiation at extremes.

The analysis is intriguing, but some experts cautioned that more research is needed to confirm the timing.

“The Holocene age estimate is only inferred, not measured, so the age is very uncertain,” says Mark Boslow, a research professor at the University of New Mexico who was not involved in the study.

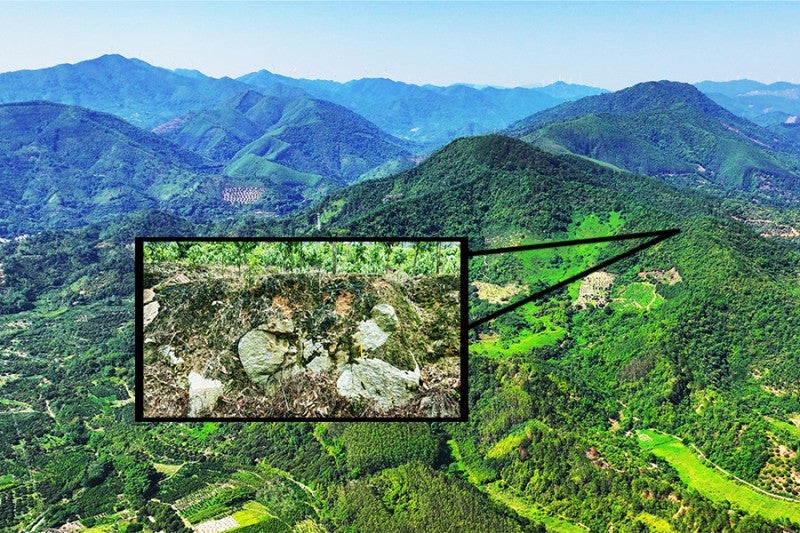

An aerial panoramic photograph of Jinlin Crater taken with a drone, showing the approximate location of the crater rim and an inset of the crater floor showing a mixture of granitic weathered soil and granite fragments.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Other experts are more optimistic: Geologist Stephen Jarrett says the team has only suggested that the impact likely occurred during the early to mid-Holocene, an estimate supported by the study data. Jaret, who was also not involved in the study, emphasizes that the researchers agreed that more work would be needed to accurately date the crater. Scientific American contacted the authors for comments.

The team analyzed rates of chemical and physical weathering to determine the age. However, these measurements are often subject to error, Jaret says.

A more accurate method would be to measure the decay rate of radioactive isotopes in rocks, such as the element argon. But it takes a lot of time and effort, Jaret says.

“Often you have to justify the next step,” he says.

It's time to stand up for science

If you liked this article, I would like to ask for your support. Scientific American has been a champion of science and industry for 180 years, and now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I was Scientific American I have been a subscriber since I was 12, and it has helped shape my view of the world. science always educates and delights me, instills a sense of awe in front of our vast and beautiful universe. I hope it does the same for you.

If you subscribe to Scientific Americanyou help ensure our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on decisions that threaten laboratories across the US; and that we support both aspiring and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return you receive important news, fascinating podcastsbrilliant infographics, newsletters you can't missvideos worth watching challenging gamesand the world's best scientific articles and reporting. You can even give someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in this mission.