How it happens6:27Scientists have discovered dinosaur mummies with horse-like hooves

It's been more than 60 million years since duck-billed dinosaurs roamed what is now known as western North America.

Or, more accurately, because they were stomping around. On your hooves.

That's according to a new study of “dinosaur mummies” – fossils in which the external anatomy of dinosaurs is reproduced in incredible detail on thin layers of ancient clay.

This means that hooves were first discovered on a dinosaur, or indeed any reptile. But the researchers behind the discovery expect there will be more of them now that people know to look for them.

“I think people's antennae will be up now to make sure there's nothing there when they dig,” said University of Chicago paleontologist Paul Sereno, lead author of the study. How it happens presenter Neil Koksal.

Conclusions published in Science magazinepaint the most complete picture to date of what duck-billed dinosaurs actually looked like.

Moreover, the study solves a long-standing mystery of how the so-called dinosaur mummies formed in the first place.

Cretaceous cows

Duck-billed dinosaurs were much more common than their better-known Cretaceous contemporaries, such as the apex predator Tyrannosaurus rex or the horned dinosaur Triceratops.

In fact, these nearly three-meter-tall herbivores were Tyrannosaurus rex's favorite food.

Also known as Edmontosaurus – since the first fossils were discovered in southern Alberta – they roamed together in giant herds, grazing on plants, much like modern cows, sheep and goats.

Also like modern grazing mammals, these dinosaurs evolved hooves, structures that protected their toes, supported their weight, provided traction, and absorbed the shock of walking and running, saving their lives.

“It's remarkably similar to a later equine or equine hoof, or something you might see on a relative, a tapir or a rhinoceros,” Sereno said.

“There's a shield on the outside, and on the underside there's sort of a soft core that really resembles the hooves of mammals, which evolved much later.”

This is an example of a phenomenon known as convergent evolution, in which different organisms independently evolve similar traits—such as the wings of birds, bats and extinct flying reptiles called pterosaurs—while adapting to similar environments or ecological niches.

What exactly is a dinosaur mummy?

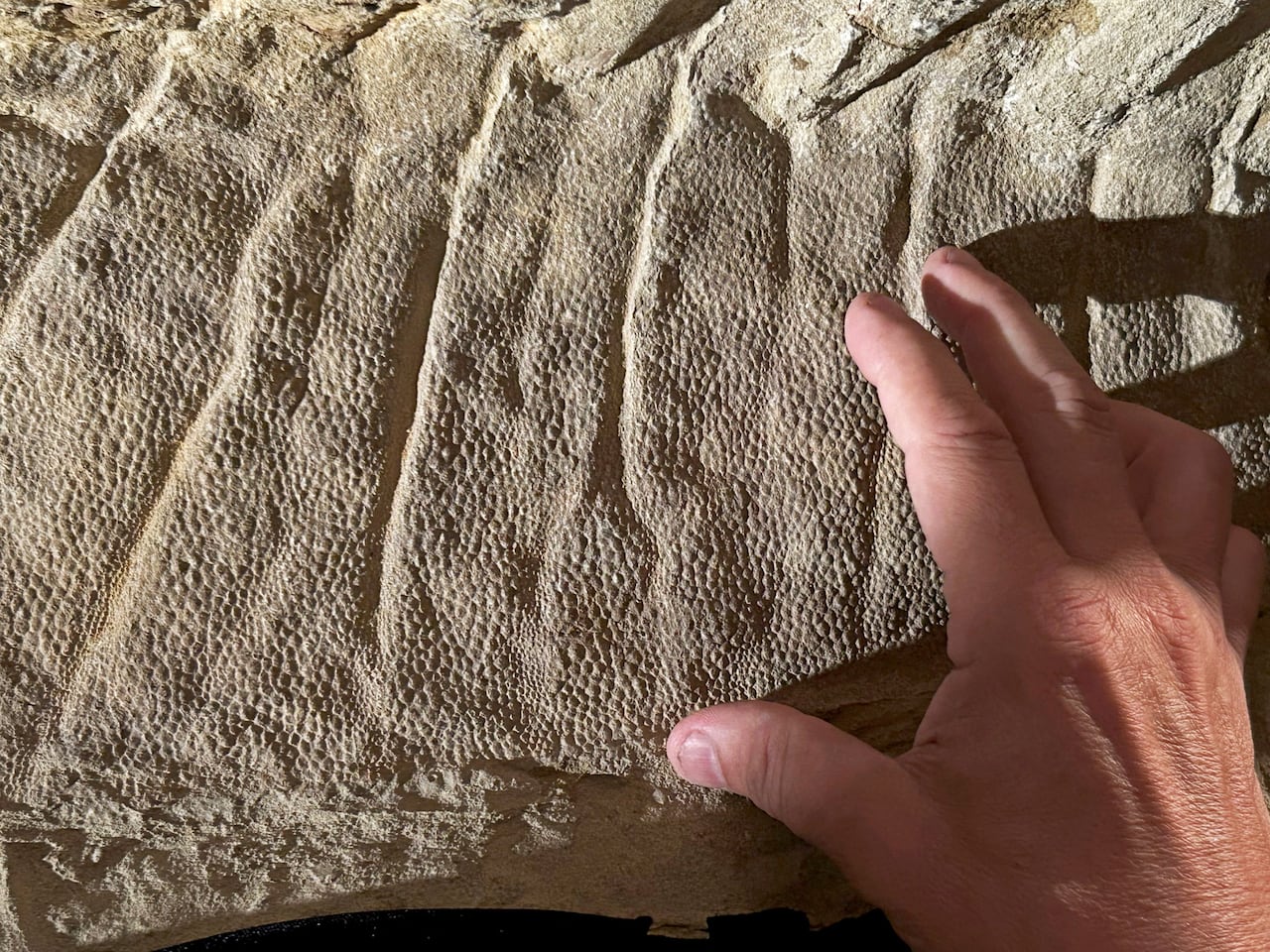

Sereno and his colleagues identified hooves on a pair of detailed fossils known as dinosaur mummies. These are skeletons that at first glance appear to be covered in surprisingly well-preserved skin.

Scientists have been discovering these types of fossils for more than a century, many of them in the badlands of eastern Wyoming, in an area known as the “mummy zone.”

Sereno and his colleagues wanted to understand the process of creating these mummies. But the name turns out to be a bit of a misnomer.

“People will think of Egyptian mummies and ask, what is a dinosaur mummy? That was our question first and foremost,” Sereno said.

Mummification usually involves the preservation of flesh, either intentional or natural. But these mummies appear to be devoid of flesh.

The study examines two duck-billed dinosaur fossils excavated in Wyoming in the early 2000s.

Sereno says the samples do not actually contain skin, DNA or tissue.

It's just clay.

Two Edmontosaurus died about 66 million years ago, possibly as a result of drought.d their desiccated corpses were covered by a flash flood, leaving them covered in a film of clay of approximately 0.0Thickness 25 centimeters.

This clay was then hardened with the help of microbes. As the skin and flesh decomposed, the bones remained, encased in clay masks that preserved the creatures' forms, including the contours of their bodies and scaly skin.

“It’s a great visualization of what the animal looked like,” Sereno said.

This style of mummification has preserved other organisms before, but scientists didn't think it could happen on land. It's possible other mummies found in Wyoming may have formed in a similar way, Sereno said.

ANDUnderstanding how dinosaur mummies form could help scientists discover more of them, says Mateusz Wosik, a paleontologist at Misericordia University who was not involved in the discovery. It is important to look not only for dinosaur bones, but also for skin and soft tissue impressions that may remain unprocessed.will die or even be taken away during excavations.

More mummies provide more information about how these creatures grew and lived, says Stephanie Drumheller, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Tennessee.

“Every time we find them, we find a real treasure trove of information about these animals,” said Drumheller, who was not involved in the study.

These images, combined with what scientists already know from other fossils, paint a detailed picture of what the duck-billed dinosaur looked like, from its head to its hooves.

According to the study, it has a crest running down its neck and back, which extends into a series of spines running down its tail. Its skin was covered in tiny pebble-like scales, no larger than those of an average lizard.

And, as we now know, it was ungulates.

“This is a milestone,” Sereno said. “Now we really know this dinosaur.”