Georgina RannardScience correspondent

NASA

NASAAccording to American media reports, the American space agency NASA will accelerate plans to build a nuclear reactor on the Moon by 2030.

This is part of the US ambition to create a permanent base for human habitation on the surface of the Moon.

According to Politico, the acting head of NASA cited similar plans by China and Russia and said the two countries “could potentially declare a containment zone” on the moon.

But questions remain about how realistic the goal and timeline are, given NASA's recent and dramatic budget cuts, and some scientists are concerned that the plans are driven by geopolitical goals.

Countries including the US, China, Russia, India and Japan are rushing to explore the lunar surface, with some planning to establish permanent human settlements.

“To properly advance this critical technology to be able to support a future lunar economy, powerful energy production on Mars, and strengthen our national security in space, it is critical that the agency act quickly,” U.S. Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy, whom President Donald Trump named as NASA's interim head, wrote to NASA, according to the New York Times.

Mr Duffy called on commercial companies to accept proposals to build a reactor that could generate at least 100 kilowatts of power.

This is a relatively small figure. A typical onshore wind turbine generates 2-3 megawatts.

The idea of building a nuclear reactor as a source of energy on the Moon is not new.

In 2022, NASA awarded three $5 million contracts to companies to design the reactor.

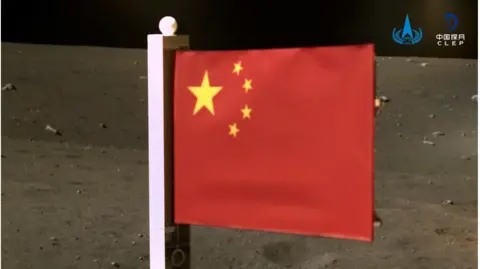

And in May of this year, China and Russia announced they plan to build an automated nuclear power plant on the Moon by 2035.

Many scientists agree that this would be the best, or perhaps only, way to provide continuous power to the lunar surface.

One lunar day is equivalent to four weeks on Earth, consisting of two weeks of continuous sunlight and two weeks of darkness. This makes harnessing solar energy very challenging.

CNSA/CLEP

CNSA/CLEP“Constructing even a modest lunar habitat to accommodate a small crew would require megawatt-scale power generation. Solar panels and batteries alone cannot reliably meet these needs,” suggests Dr Sungwoo Lim, senior lecturer in space applications, research and instrumentation at the University of Surrey.

“Nuclear power is not just desirable, it is inevitable,” he adds.

Lionel Wilson, professor of earth and planetary sciences at Lancaster University, believes it is technically possible to put reactors on the Moon by 2030, “if there is enough money”, and points out that there are already small reactor projects.

“It's just a matter of making sure there are enough Artemis launches by then to build out the infrastructure on the Moon,” he adds, referring to NASA's Artemis spaceflight program, which aims to bring people and equipment to the Moon.

There are also some safety issues.

“Releasing radioactive materials through the Earth's atmosphere raises safety concerns. This requires a special license, but it is not insurmountable,” says Dr Simeon Barber, a planetary scientist at the Open University.

Duffy's directive comes as a surprise following recent turmoil at NASA after the Trump administration announced a 24% budget cut for NASA in 2026.

This includes cutting a significant number of science programs, such as Mars Sample Return, which aims to return samples from the planet's surface to Earth.

Scientists are also concerned that the announcement is a politically motivated move in a new international race to the moon.

“It feels like we're going back to the old competitive days of the early space race, which is a little disappointing and worrying from a scientific perspective,” Dr. Barber says.

“Competition can create innovation, but if the focus is on national interests and establishing ownership, you may lose sight of the bigger picture of exploration of the solar system and beyond,” he adds.

Mr Duffy's comments about the possibility of China and Russia potentially “declaring a protected zone” on the Moon appear to refer to an agreement called the Artemis Accords.

In 2020, seven countries signed an agreement to establish principles for cooperation between countries on the surface of the Moon.

The agreements include so-called safety zones that will be created around the operations and assets that countries build on the Moon.

“If you build a nuclear reactor or any other base on the moon, you can start to claim that there is a safety zone around it because the equipment is there,” Dr. Barber says.

“For some people, it's like, 'We own this piece of the moon, we're going to work here, and you can't come in,'” he explains.

Dr. Barber notes that there are hurdles that must be overcome before placing a nuclear reactor on the Moon for human use.

NASA's Artemis 3 goal is to send humans to the lunar surface in 2027, but it has faced a number of setbacks and funding uncertainties.

“If you have nuclear power for a base, but you don't have the ability to get people and equipment there, then it doesn't make much sense,” he added.

“The plans at the moment don't seem very coherent,” he said.