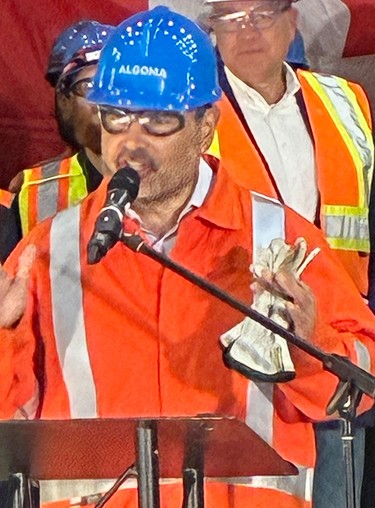

Canadian steel magnate Barry Zekelman has emerged as one of Ottawa's harshest critics. But will the brash, competitive, Ferrari-loving entrepreneur get his message through before it's too late?

Article content

Canadian steel billionaire Barry Zekelman, an ardent supporter of United States President Donald Trump, knows what it feels like to shout into the wind.

In June, around the time the U.S. raised tariffs on foreign steel to 50 per cent, he flew to Ottawa to brief Canada’s newly minted federal cabinet ministers on how to respond. Zekelman and a delegation of steel executives told Industry Minister Mélanie Joly and others to slash the flow of foreign steel entering Canada by about 80 per cent.

Article content

Article content

Advertisement 2

Article content

But the cabinet had different ideas, and Prime Minister Mark Carney a couple of weeks later announced that the overall volume of foreign steel allowed to enter Canada duty-free could remain at roughly 2024 levels.

Article content

“They couldn’t have done worse,” Zekelman said. “I called them socialist, communist bastards, and I said you should all rot in hell. I texted it to them … and Joly, she’s like, ‘Barry, calm down. I’m just getting on a plane.’ I’m like, ‘Nope, go f*** yourself.’”

It was neither his first nor his last scrap with a powerful politician. Friends call him “The Man of Steel,” in part because he wears his heart on his sleeve and never hesitates to say what’s on his mind or drop an f-bomb or two into conversation.

As Canada rethinks its path forward amidst a shifting global trade order, Zekelman, a 58-year-old who drives Ferraris but never graduated from university, has emerged as the harshest critic of Ottawa’s strategy thus far. His defence of the logic behind Trump’s tariffs on Canadian steel, even as they cause layoffs and losses in the sector, has irked friends, business associates, rivals and politicians alike.

I called them socialist, communist bastards, and I said you should all rot in hell

Barry Zekelman

The chief executive of the Chicago-headquartered Zekelman Industries Inc. oversees an empire of steel companies that produce more structural tubing than any company in North America. His career, however, started in the heart of Canada’s rust belt, just outside Windsor, Ont., where he grew up and near where he continues to live, except when the trappings of a billionaire’s lifestyle — a house in Arizona’s Paradise Valley or a pied-à-terre in New York City’s West Village — pull him elsewhere.

Article content

Today, his company’s structural tubes are found in warehouses, big box stores, stadiums and rail cars across Canada — and even in a portion of Trump’s controversial border wall with Mexico. His companies make plumbing pipe and other products and one of them, Z-modular, is one of if not the largest modular home businesses in North America, building multistory, multifamily steel structures.

Article content

But the rise of Zekelman’s empire has coincided with the emergence of steel industries in China and other developing countries that flooded the global market with product and ultimately forced plant closures and job losses in many communities across North America. Throughout that period, he thrived even as others failed, although he blamed trade policy for forcing him to close at least one plant.

Some take the view that even though his private steel empire started in Canada, it is now largely based in the U.S., giving him much to gain from tariffs on Canadian steel.

But he styles himself as a champion of blue-collar workers. In his view, as Canada raised its environmental and labour standards for steel producers, it simultaneously allowed steel from countries that lack such regulations, such as China, to freely flow into the country.

Article content

Zekelman said he is tired of watching communities empty out as manufacturing plants shut down and wants to see a change in policy that stops countries from sending what he called unfairly subsidized steel into Canada.

“I’m not in it because I need hundreds of millions more dollars,” he said. “If that’s part of success, then great, but take everybody else along with it. These people need this.”

So far, he said he hasn’t spoken to or heard from Joly, nor any other cabinet member, since sending his colourful texts in June. A spokesperson for Joly declined to comment. Nor has anyone taken him up on his offer to help negotiate a trade pact with Trump, whom he has met on several occasions.

Although he is liked by many in the industry, there are those who say his strong-arm approach only works so often.

“The story of Barry Zekelman is complicated because if you try to compete with him, god save you,” said one steel industry veteran who asked not to be named. “But if you’re an employee, it may actually be good.”

Nonetheless, Canada is moving in the protectionist direction Zekelman wants, though not as quickly as he’d like.

The story of Barry Zekelman is complicated because if you try to compete with him, god save you

Steel industry veteran

In July, one month after Carney’s first steel announcement, he returned with a new policy to crack down on foreign steel that set the level of duty-free imports allowed into Canada at 50 per cent of 2024’s levels and placed 50 per cent tariffs on steel above that. But the policy only applied to countries that don’t have a free trade agreement with Canada.

Article content

Zekelman, who said he tries to understand why people behave as they do, suggested Carney was likely a “nerd” in his childhood who needs to show some courage on trade policy.

“I’m sure he got teased and the s*** beat out of him,” he said, “and every guy was a bully, and that’s wrong. This is his chance now to stand up to the bully.”

The bully in this scenario is not Trump, who enacted 50 per cent tariffs on foreign steel to devastating effect in Canada, but China and other exporting countries, who Zekelman sees as bullies for sending cheap, unfairly subsidized goods into Canada and the U.S., hurting manufacturers and their blue-collar workers here.

‘I’m going to subsidize it’

On Sept. 26, Zekelman sent a letter to all his employees at his only Canadian steel plant, Atlas Tube Inc. in Harrow, Ont. — compared to a dozen or so in the U.S. — to inform them that hard times had arrived.

“Harrow is our lowest-cost, most productive plant in the entire company,” he said in the letter, “but it is impossible to overcome US$250 to US$300 per tonne in duties.”

The U.S. tariffs on Canadian steel have been costing his company $6 million to $7 million per month, only some of which could be passed on to suppliers, the letter said.

Article content

As a result, the Harrow plant will serve just the Canadian market, and a U.S. plant will take over most of its production for the U.S. market. Production in Harrow will drop 45 per cent from about 2,200 tonnes per day to about 1,200 tonnes, the letter said. Yet there would be no layoffs.

“I can’t fly around on a private plane and then put them out of work,” said Zekelman, who has more Ferraris than he can remember, a 280-foot yacht — purchased from Hollywood film director Steven Spielberg — and a private jet. “I’m going to subsidize it and f****** eat it.”

Article content

Besides, he said, the Harrow plant is his favourite by far.

In 1986, when Zekelman was 19, his father passed away at the age of 68 and left the plant to him and his two brothers. Zekelman was at York University and his older brother, Alan, was pursuing a master’s degree.

He said his father, Harry, a Polish Jew, escaped the Holocaust by joining a regional tank unit that made its way across Europe during the Second World War. By the end of the war, his family had all been killed, and he was living in a refugee camp. Eventually, the elder Zekelman made his way to Canada, bringing a restless energy to Windsor, where a distant cousin operated a scrapyard.

His father started collecting scrap for the family, plowing whatever he earned into new ventures. He tinkered with making electrical boxes, chain-link fences, exhaust tubing for the auto sector, mobile homes and structural tubing.

Article content

“He wore a suit with a vest that had three pockets and that was his filing cabinet,” Zekelman said. “And he wore that every day. I still remember the papers sticking out of there.”

Neither needed more than a few hours of sleep, so he said they would sometimes wake up in the middle of the night and take drives around the countryside together.

He doesn't have any formal business education … But the guy's an engineer by any other name

childhood friend Curtis Cusinato

The elder Zekelman was “a multimillionaire,” but only barely, according to Curtis Pope, a personal accountant for Zekelman and his father’s steel tubing company before that. The inheritance was primarily real property, he said.

Zekelman said his father spent the last few years of his life consumed with trying to fix his steel tubing business, putting the company into bankruptcy and then buying the assets back.

That passion for the business flowed to his sons, who tried to make the plant in Harrow work even as it was losing money.

“My father had really derelict apartment buildings in Windsor that he left us,” Zekelman said. “As soon as my dad died, I got a notice from the fire marshal that we had to replace all the doors in an apartment building and the carpet and rebuild the fire escapes, and I was like, ‘With what?'”

He was cash poor, but fascinated with the machinery inside the plant.

Article content

His childhood friend, Curtis Cusinato, who would become his outside counsel, said that as a kid growing up in a wealthy enclave of Windsor, Zekelman had an engineer’s mind, taking apart and reassembling their motorbike engines, for example. Fixing the steel plant, which kept jamming up, fit his skill set, he said.

“Look, he doesn’t have any formal business education, certainly no college degree,” Cusinato said. “But the guy’s an engineer by any other name.”

‘I want a Ferrari’

To motivate the five employees at the plant he inherited in 1986, Zekelman said he adopted a “gain-sharing” program. In addition to a base hourly wage, the workers also earned a bonus hourly wage that rises or falls based on the plant’s hourly steel production.

After about eight months, he said the plant made its first monthly profit — $4,000 — which doubled the next month and continued to increase. Within about five years, he bought his first Ferrari — a 328, what Tom Selleck drove in Magnum P.I.

“It was like $120,000 and it was most of what I had in the bank,” he said. “I just said, ‘I want a Ferrari.”

As the plant grew more profitable, and Zekelman transitioned into adulthood, he emerged as a mogul in the Windsor area, eventually becoming a co-owner of several gyms and providing financing to a friend who ran strip clubs, including Danny’s, an all-male strip club for women, located on prime waterfront real estate in the city.

Article content

Zekelman spent most of his hours in the Harrow plant, often rolling up his sleeves and fixing machines whenever they broke down, which was often. As production grew and competitors were acquired, several workers said he rewarded them with generous pay and benefit packages, plus an array of bonuses, such as cheques when gas prices spiked.

One worker, who has spent decades at the plant, said an “us against the world” mentality developed in Harrow.

“Barry would give us pep talks,” he said. “He’d say, ‘Look, this is the next pin that I want to be able to put right here,’ and we would freaking take another competitor down.”

But even as Zekelman’s success grew, he had to make decisions about which plants could survive as global excess steel capacity continued to increase, leading to lower steel prices and waves of imports.

In 2015, he shuttered a plant in Welland, Ont., that had what he described as “a state-of-the-art” stretch mill, putting 350 people out of jobs. He blamed open trade policies in Canada and the U.S. for the closure because South Korea started sending the same product — tubular goods used for fracking fossil fuels — made at his plant into both countries at prices he couldn’t beat or match.

Article content

“It’s gone because Canada did nothing about the imports and neither did the U.S., so it got annihilated,” he said.

That particular situation also rankled one of his competitors, Butch Mandel, chief executive of Concord, Ont.-based Welded Tube of Canada Corp., who said South Korea doesn’t even have an oil and gas industry.

“There’s a difference between fair trade and free trade,” he said, “and we’ve got countries with free trade agreements that are unfair traders. Our government doesn’t distinguish amongst them.”

For example, in 2024, Canada erected 25 per cent tariffs on steel imported from China, which the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has suggested is creating an excess steel capacity crisis.

In 2024, China produced 118 million tonnes of steel just for export, which is more than the U.S., Canada and Mexico produced on a combined basis. The OECD earlier this year estimated that Chinese steel companies receive 10 times the average subsidization rate as steel companies in its member countries, which include most of the Americas and Europe as well as other countries.

Zekelman and other steel producers say the Canadian tariffs on Chinese steel don’t go far enough.

Article content

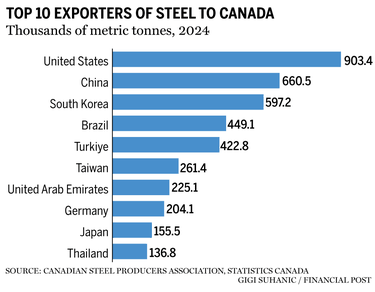

For example, South Korea imported 8.2 million tonnes of steel from China in 2024, according to data from the Canadian Steel Producers Association (CSPA), an industry lobby group. It also exported 5.9 million tonnes to Canada.

Zekelman and Mandel say that some of the steel from China going to South Korea may be re-exported to Canada. In 2024, South Korea was Canada’s third-largest source of steel imports, behind the U.S. and China.

The CSPA has ranked South Korea as the second-worst trade offender in Canada, behind China, pointing out there have been multiple cases over the years that challenged its steel imports under anti-dumping and other rules that prohibit selling in foreign markets at artificially low prices.

Although Canadian steel producers have prevailed in most of the trade cases, the CSPA said the system is slow and expensive. Each case can take up to 18 months until a judgment is rendered, and they cost millions of dollars. At the end of the case, a steel producer in another country may start dumping the same product into Canada, thereby rendering the judgment ineffective.

“Every year is a bad year on steel dumping,” Catherine Cobden, president of the CSPA, said. “What changes is who’s dumping.”

Article content

‘We prospered under the old system’

In September, Carney travelled to New York to give a talk that explained some of the reasons why he may not want to slap tariffs on all steel imports. As Canada’s trade with the U.S. declines, he said he is hoping to make up the difference by growing its trade with other countries.

“I’ll start by admitting upfront that we prospered under the old system,” he said. “We would like the old system back.”

As a “middle power,” Carney said Canada thrived under a rules-based trading system when it had open access to the U.S. market and “collective security was anchored” by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

But the steel sector represents only one of his concerns. He also has to contend with U.S. tariffs on the auto sector, aluminum, softwood lumber and other products while keeping the overall health of the economy in mind.

Steel importers have said that even the steel tariff policy on non-free trade countries that Carney put in place in July is forcing them to scale back their businesses. Blocking too much foreign steel could create shortages or price spikes that ripple through the rest of the economy at a precarious moment.

“Steel is literally everywhere,” Colin Mang, a professor of economics at McMaster University in Hamilton, said.

Article content

Buildings, automobiles, railroads, boats, grocery store shelves, lamp posts, traffic lights, household appliances and many of the building blocks of modern society require steel, as do military applications, from planes to equipment to weapons, he said.

There is at least one point on which Carney and Zekelman might agree: Canada has been disproportionately open to foreign steel.

Around two-thirds of the steel used in Canada is foreign-made, compared to less than one-third in the U.S. and one-sixth in Europe, the prime minister said this summer.

Where they disagree is what to do about it. Zekelman said he advised Carney’s cabinet to slash the amount of foreign steel by 80 per cent, but that hasn’t happened.

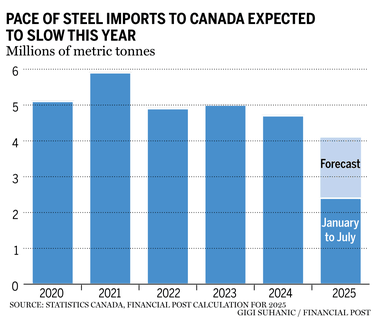

Through the end of July, about 2.36 million tonnes of foreign steel had entered Canada this year, according to Statistics Canada. That pace would amount to a 15 per cent year-over-year reduction from 2024.

Meanwhile, the Canadian steel sector’s annual production has declined to around 12 million tonnes per year from a peak of 16.5 million tonnes in 2000.

Of course, steel producers say that when Carney talks about prosperity, he isn’t thinking about just steel.

Robert Lighthizer, who served as U.S. Trade Representative under Trump during his first term, has said the rules-based “free trade” system promoted by Carney chiefly benefited people employed in services, who are often located in urban areas, and left rural economies that relied on manufacturing in dire straits.

Article content

“Canada has always had a luxury,” Zekelman said. “The luxury that Canada has had is that if our tonnes get displaced (by foreign steel), we can always ship across the border to the U.S.”

But he said some Canadian companies used foreign steel to make goods that they then exported to the U.S. market, thereby undercutting producers there and upsetting politicians such as Trump.

‘Why don’t you threaten them?’

Driving back to his home in Tecumseh on Lake St. Clair in late September, Zekelman became angry as he whizzed past an array of steel H beams set for use in a highway overpass.

It’s a type of beam that he said isn’t manufactured in Canada, but it was being used in a provincial public works project even after Ontario Premier Doug Ford and Carney both promised to “Buy Canadian” steel to help revive the sector.

“I get crazy upset and emotional because I just had a guy lie to me to my face,” he said, referring to Ford. “He said, ‘We’re gonna use all Canadian (steel). We’re moving it all over. Well, you didn’t; it’s right there.”

It is not the first time that Zekelman and Ford have locked horns about the use of foreign steel.

Article content

In May 2023, when Nextstar Energy Ltd. was building Canada’s first electric-vehicle battery plant in Windsor, work suddenly stopped because the company threatened to abandon the project unless Canada matched the billions of dollars in subsidies that the U.S. was then promising.

Article content

Eventually, Ontario and the federal government ponied up. The Parliamentary Budget Office estimated the project received $1 billion for construction support and is set to receive an estimated $17.6 billion in production subsidies once it begins operations.

That should have given Ontario more than enough leverage to insist that the project use Canadian steel, Zekelman said.

“I scream at Doug Ford, and he’s like, ‘It’s a private deal,’” he said. “I said they just stopped construction and threatened you until you gave them more incentives, so why don’t you threaten them and say, ‘Hey, you don’t get to build this unless you use Canadian steel.'”

Even though his plant was just 30 kilometres away, Zekelman said imported steel was used to construct the 4.23-million-square-foot plant, which was completed in late September. Neither Nextstar nor Ford’s office provided comment for this article.

He said the province could have substituted pipe piling, which he makes using Canadian steel purchased from a plant in Nanticoke, Ont. That steel would have had the added benefit of a lower carbon emissions profile than most imported steel, he said.

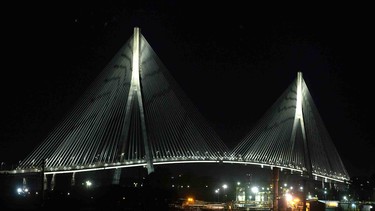

Though he didn’t win this time, he said his advocacy has paid off in the past. The Gordie Howe Bridge, which connects Windsor to Detroit, used thousands of tonnes of his company’s steel tubing rather than beams, but he said it was a one-off. “Nothing changes,” he said.

Article content

Article content

‘Bankrupt because of trade’

Zekelman’s unflinching support for Trump and his tariffs has at times irked those who know him.

“I know Barry extremely well and have for decades,” Mandel at Welded Tube said. “I consider him a friend and he’d say the same, and yet Barry can sometimes, for reasons that escape me, say things that are mystifying.”

Mandel said U.S. tariffs are also costing his company millions of dollars every month, although his U.S. operations are making money.

Most of Zekelman Industries’ plants are located in the U.S., which has fuelled speculation that Zekelman stands to benefit from U.S. tariffs on the whole. There has even been speculation that he likes the tariffs because they would weaken steel companies and allow him to follow the old “buy low, sell high” adage to finally buy a mill.

Currently, none of his companies melt their own steel, forcing him to buy steel and then shape and weld it into tubing, pipes or other forms. But Zekelman said his views on Trump and trade are misunderstood.

If the tariffs disappeared tomorrow, I'd throw a party

Barry Zekelman

“If the tariffs disappeared tomorrow, I’d throw a party,” he said.

Nonetheless, his support for Trump has not wavered. In 2022, he and his companies were fined $1.2 million by the U.S. Federal Election Commission for breaking rules against foreign nationals donating to U.S. political campaigns after giving $2.2 million in 2018 to a group set up to support Trump.

Article content

Zekelman disputed some of the reported details from the case, but said his support for Trump flows from his belief that the U.S. president wants to revitalize the domestic industry and he questions whether Canadian politicians, across parties, see things the same way.

Canada has focused on reining in the carbon emissions profile of its steel sector, he said, while other countries focus on creating competitive steel for export. Even as the trade war batters the sector, he said government intervention continues to miss the mark.

Article content

For example, shares in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont.-based Algoma Steel Inc. have declined 63 per cent this year, and chief executive Michael Garcia has said the company is fighting for survival as its U.S. sales decline from more than 55 per cent of revenues to what he predicted may be zero by year-end.

In September, the federal government announced it would provide Algoma a $400-million loan, while Ontario kicked in $100 million. As part of the announcement, Algoma said it would accelerate the demise of its coal-based blast furnace and coke ovens and instead use an electric arc furnace, which would lower its greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2022, the federal government provided $200 million to Algoma to offset the nearly $900-million cost of switching to an electric arc furnace, and an Algoma spokesperson said Ontario will provide additional assistance on the “cost and availability of electricity” after it makes the transition.

Article content

“Algoma doesn’t need the money,” Zekelman said. “They need the market, and the only way to get the market is to push out those offshore imports.”

Shutting down the blast furnace, he said, will only increase Algoma’s costs at the exact time it needs costs to go down because it can’t sell into the U.S. market. Instead, it must broaden its market share in Canada.

Zekelman had been rumoured as a potential buyer of Algoma earlier this year. In 2024, he disclosed that he owned five per cent of the company, but he has since sold down his shares to three per cent.

Buying the plant as a standalone asset was never part of the plan, he said. Rather, his companies had been part of a group trying to combine Algoma with other steel assets — to supply his plants — but that deal fell apart months ago. Algoma by itself, he said, is too small to supply all his plants.

“Algoma has been bankrupt a bunch of times,” he said. “But all of these mills go bankrupt because of trade. There’s been some mismanagement and bad decisions and certain stuff, but it was all surrounded by trade and getting dumped on.”

‘I have a huge chip on my shoulder’

On the last day of September, Zekelman was contemplating an email he received in response to a Zekelman Industries email campaign promoting domestic manufacturing. One recipient wrote to ask him what “jackass” had given out his email address.

Article content

Never one to back down from a fight, Zekelman made some inquiries and determined that the sender had entered his email address as part of a request for information on a Zekelman Industries website.

“I wrote back to him, and I don’t know why I did this, I just felt in the mood this morning,” he said. “I said, ‘You requested info from our website a few months ago, so I guess you’re the jackass we got it from.’ I said, ‘Sorry, we will remove you at once. Have a great day.’”

The conversation didn’t end there, but Zekelman said he had a laugh about the whole thing.

“I have a huge chip on my shoulder,” he said. “I still do about not having higher education, about being that guy from Windsor — ‘Oh, you’re from Windsor’ — because Windsor was a s***hole, and about being the little Jewish guy who got chased home from school.”

Canada is going to be left sitting there like a deer in the headlights

Barry Zekelman

Zekelman said he was constantly being talked down to by people who held degrees from fancy universities even though he had far outperformed them in the business world.

Most people, he said, still believe he inherited a thriving steel business and rode through life with a silver spoon in his mouth. But he said he has had his share of hard times, and even after making billions of dollars, he still rises early, hits the gym, travels frequently and works often.

Article content

In 1998, long before he was a billionaire, Zekelman said he took a risk and decided to “mortgage everything” so he could invest $40 million in new machinery. While bringing those operations online, his wife died in a car accident, leaving him a single father to a 15-month-old daughter.

“I woke up at five in the morning, and she’d lie on the bath mat beside me when I showered at six,” he said. “Then someone would come in, and I’d be home at night to feed her and bathe her and do whatever with her and do all that.”

But the expansion proved prescient: one competitor credited it with catapulting his success.

Zekelman went on an expansion spree until 2006, when the U.S.-based private-equity firm Carlyle Group Inc. purchased a 55 per cent stake in Atlas Tube to merge it with JMC Steel Group in a deal valued at around US$1.5 billion. The original buyout was supposed to “secure his future,” he said, so he never had to worry again.

“I say that, yet I worry more every day today than I did then,” he said.

Two years later, Carlyle Group, then the controlling shareholder, cut a deal to sell the company to Russia’s Novolipetsk Steel OJSC. Zekelman called it one of the worst days of his life.

But as the great financial crisis of 2008 shook global markets, the deal fell through. In 2011, he repurchased the company from Carlyle.

Article content

Now, he said he’s concerned that everyone except Canada understands that Trump’s protectionism is here to stay.

Zekelman pointed out that the European Union on Oct. 2 proposed to double its tariffs on foreign steel to 50 per cent, which he took as a sign it was trying to align with Trump.

“I would not be surprised if you saw a major CUSMA announcement that did not have the ‘C’ in it, and I mean within days,” he said. “I don’t know anything, but I suspect it. Canada is going to be left sitting there like a deer in the headlights, going, ‘Oh s***, what just happened to us?’”

• Email: [email protected]

Article content