November 3, 2025

4 minute read

The US may soon lose its measles-free status

The Pan American Health Organization meeting this week will address the resurgence of measles in America.

A vial of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. The US could risk losing its measles-free status if current outbreak trends continue.

PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP via Getty Images

If current trends continue, North America could soon become a hot spot for persistent measles transmission. Canada could lose its measles-free status this week, and the United States may not be far behind.

The Pan American Health Organization's (PAHO) key committee on measles and rubella will meet this week to discuss whether North American countries have lost measles elimination status, meaning the measles virus has become endemic in those countries. A country is considered measles endemic if there has been continuous transmission from a single outbreak of the virus that lasted 12 months or longer.

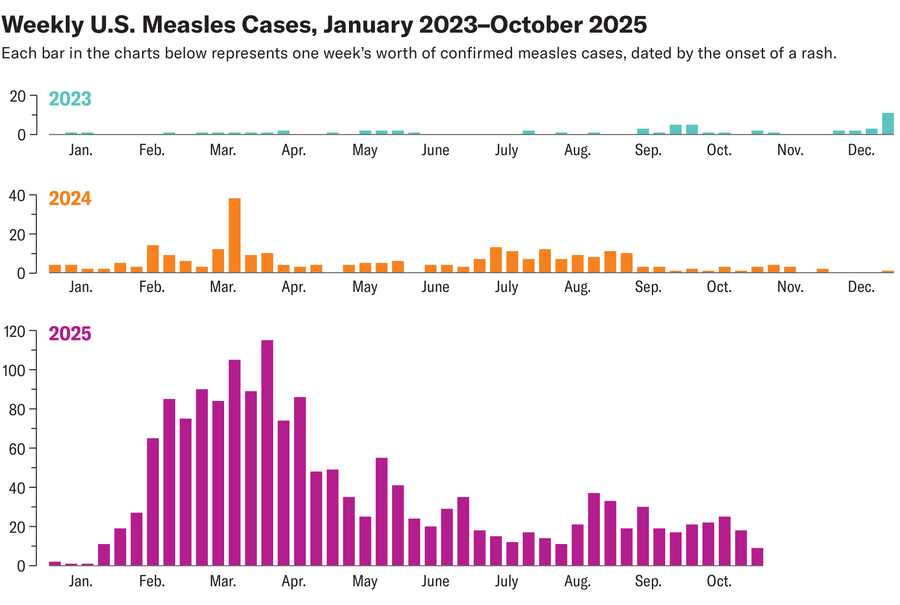

Canada has probably already passed this milestone; The country has seen a single outbreak with more than 5,100 measles cases since October 2024, the data shows. information about his health. The US is also on shaky ground. An outbreak of 762 cases in West Texas that began in late January 2025 was declared over on August 18. However, health officials are investigating ongoing outbreaks in South Carolina and Utah. If investigations are able to link these outbreaks to the original cases in Texas, and if public health authorities fail to bring them under control by January 2026, the US could also lose its measles elimination status.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“I expect we will lose the exemption status,” says David Higgins, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “We're heading straight for it.”

Experts reach these conclusions by analyzing epidemiological data from outbreaks as well as molecular data that can determine whether individual viruses belong to the same chain of transmission, says John Kim Andrus, chairman of PAHO's regional review panel. The commission is also examining the country's vaccination coverage and its ability to detect measles cases. For example, if there are areas where public health officials never report illnesses with rashes and fevers, that's a red flag that measles may be spreading undetected. The commission also considers each country's ability to strengthen its public health system and the sustainability of its programs. The process is “rigorous and detailed,” Andrus says.

Canada first eliminated measles in 1998, and the United States in 2000. In 2016, the entire Americas region declared the disease eradicated, but outbreaks in Venezuela in 2017 and Brazil in 2018 overturned that declaration. Last November, PAHO found that both countries transfer interrupted successfullywhich will make America measles-free again.

Measles can have serious long-term consequences, including hearing loss, decreased immunity from previous infections with other viruses and pneumonia. One in every 1000 cases of measles causes encephalitis“This can lead to permanent brain damage or death,” says Lisa M. Lee, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Virginia Tech and a former official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US saw more 1,600 cases and three confirmed deaths so far this year.

“Seeing this happen right now in the U.S. is really heartbreaking,” Lee says.

Efforts to control measles are worth the cost, says Kimberly Thompson, founder of Kid Risk, a nonprofit organization that analyzes pediatric risks. Thompson's work estimates that the net economic benefit of investing in measles and rubella vaccination in the United States will be $310 billion and $430 billion in avoided costs of measles and rubella treatment, respectively. This does not include the additional economic productivity gains gained from parents and children avoiding sick leave.

“It's a huge return on investment, not just from a financial standpoint, but from a health standpoint, it's quite significant as well,” Thompson says.

The problem is that measles is incredibly contagious. In an unvaccinated population, each case could generate 12 to 18 new cases, according to Amy Winter, an epidemiologist and biostatistician at the University of Georgia. Winter and her colleagues estimated that with vaccination coverage of 84 percent each case can still cause two to three new cases— infectiousness similar to seasonal flu or the original COVID variant. That's why 95 percent vaccination coverage is the threshold for herd immunity—the point at which there are enough people in a population with immunity to prevent the disease from continuing to spread.

According to Winter, the cause of outbreaks in the United States is unvaccinated people. The solution is to increase the number of children who receive measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccinations. To do that, public health officials can expand access to vaccination clinics and ensure patients receive reminders when it's time to get their shots, says Higgins of the University of Colorado. Pediatricians and family physicians are at the forefront of efforts to address parents' concerns and concerns about vaccinations.

In the United States, the CDC is responsible for coordinating the nationwide public health response to measles. The Trump administration has proposed cutting the agency's budget by $5 billion, and more than 3,000 employees have been laid off or resigned since January. Much of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is currently closed, as is the rest of the federal government.

In this sense, the loss of measles elimination status in the United States could signal an alarm that the country is losing its ability to deal with public health threats.

“If you can't stop measles transmission,” Andrus says, “how do you expect to respond to the next pandemic?”

It's time to stand up for science

If you liked this article, I would like to ask for your support. Scientific American has been a champion of science and industry for 180 years, and now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I was Scientific American I have been a subscriber since I was 12, and it has helped shape my view of the world. science always educates and delights me, instills a sense of awe in front of our vast and beautiful universe. I hope it does the same for you.

If you subscribe to Scientific Americanyou help ensure our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on decisions that threaten laboratories across the US; and that we support both aspiring and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return you receive important news, fascinating podcastsbrilliant infographics, newsletters you can't missvideos worth watching challenging gamesand the world's best scientific articles and reporting. You can even give someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in this mission.