The holiday’s real roots lie in abolition, liberation, and anti-racism. Let’s reconnect to that legacy.

Children eating Thanksgiving dinner in Harlem.

(Bernhard Moosbrugger / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

It’s a good thing conservatives know nothing about the actual history of this country they claim to love so much—otherwise, they’d probably launch a War on Thanksgiving. That’s because, if you study the path that Thanksgiving took on the way to its current culturally dominant presence in the calendar, it becomes clear that it’s low-key one of America’s wokest holidays. Far from being an eternal symbol of Pilgrims-and-Indians lies, Thanksgiving was, for a good portion of its history, a symbol of social reform and Northern abolitionism—a day the white slaveholding South held in disdain and refused, for decades, to celebrate. The myth of Thanksgiving isn’t just in sanitized denials of white settler-colonial violence and Indigenous genocide. It’s also in the fiction that the holiday itself has only recently become “politicized,” when it was never apolitical to begin with.

It’s important to recognize that New England’s Puritan colonists often observed days of thanksgiving—think small “t”—to celebrate plentiful harvests and other communal successes. Likewise, Native American traditions of feasts and festivals for giving thanks date back thousands of years. The first national day of Thanksgiving was declared in a 1789 proclamation issued by President George Washington. Presidents John Adams and James Madison also declared days of thanksgiving during their terms, but none of those became a recurring annual holiday. Historian Joshua Zeitz notes that “by the late 1840s, some form of harvest thanksgiving celebration was observed in 21 states,” but the dates of each observance differed based on each governor’s choosing. Southern states were among those celebrating, but as anti-slavery sentiment grew more fervent and pervasive in the North, Thanksgiving took on new sectional meanings. As historian Matthew Dennis writes in Red, White, and Blue Letter Days, Southern “governors sometimes feared the feast as an abolitionist Trojan Horse”—a worry that wasn’t entirely baseless.

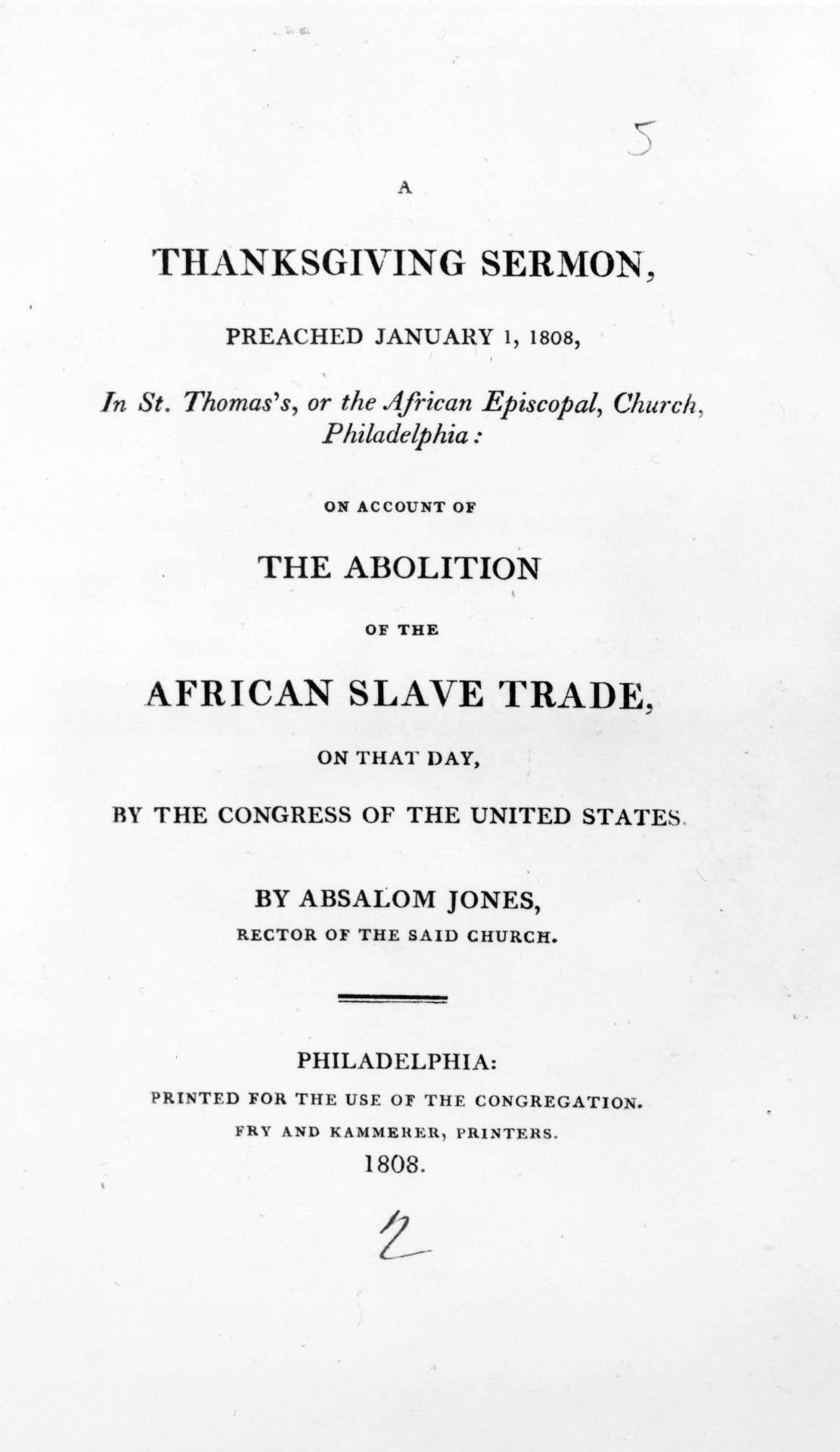

For decades, Northern antislavery clergy—especially New England’s evangelical Protestant ministers—had already been using Thanksgiving to deliver their most impassioned antislavery denunciations. On January 1, 1808, Black abolitionist and Episcopal priest Absalom Jones preached “A Thanksgiving Sermon,” recognizing the first day of the federal ban on transatlantic trafficking of Africans into America to be enslaved. The Rev. Jones suggested that January 1 should be annually observed as a “day of publick thanksgiving” to “remember the history of the sufferings of our brethren” and to commemorate the end of “the trade which dragged your fathers from their native country, and sold them as bondmen in the United States of America.”

In fact, the date did become an annual day of Thanksgiving for Northern Black communities, at least until the Civil War and emancipation, particularly in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. Historian David Waldstreicher writes that celebrations included a street parade to the church, followed by “a reading of Congress’s act abolishing the slave trade, much as white celebrants read the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson’s inaugural address, or other texts.”

The second national day of Thanksgiving declared by President Washington, February 19, 1795, saw Boston preacher Thomas Baldwin issue a plea that “the day soon arrive when not difference of climate or features nor the color of the skin—when nothing but crimes shall consign any of the human race to slavery.” In his Nov. 26, 1835, Thanksgiving sermon, New Hampshire’s Rev. Calvin Cutler called slavery “a standing memorial of our shame and hypocrisy,” labeling the institution a betrayal of the country’s professed ideals and a threat to freedom of all. “When the nation hold as self-evident truths, ‘that all men are created equal, endowed with certain inalienable rights’… [yet] one sixth of this very nation have these inalienable rights wrested from them by violence…. Is there no danger that our liberties will be infringed and destroyed, when the nation by their practice give the lie to their profession?” Cutler’s sermon text reads.

Thirteen years later, on the Thanksgiving just weeks after the election which gave Zachary Taylor the presidency, Unitarian minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson—radical abolitionist, mentor of Emily Dickinson, friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, and later, a supporter of John Brown’s 1859 armed rebellion—bemoaned the fact that there would be “another slaveholding President at the head of this nominally free Republic,” and warned the time had arrived when the North “could go no farther in its subserviency to the Slave Power.”

And there is Boston-based Unitarian minister Theodore Parker’s November 28, 1850, sermon for Thanksgiving, delivered just two months after Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which ordered that Black folks who had escaped bondage be captured and returned to their so-called masters, even if they were in free states. The demand that free Northern states comply with Southern slavery was not just gross federal overreach but belied the South’s professed belief in states’ rights. (Sound familiar?) Parker’s fiery Thanksgiving sermon laid bare how the law had intensified sectarian passions.

“I think I know of one cause which may dissolve the Union—one which ought to dissolve it, if put in action,” Parker announced. “That is, a serious attempt to execute the Fugitive Slave Law, here and in all the North. I mean an attempt to recover and take back all the fugitive slaves in the North, and to punish, with fine and imprisonment, all who aid or conceal them. The South has browbeat us again and again.… She has imprisoned our citizens; driven off, with scorn and loathing, our officers sent to ask constitutional justice. She has spit upon us. Let her come to take back the fugitives—and, trust me, she will wake up the lion.”

By the 1850s, white Southerners had already begun a kind of massive resistance to Northern influence, reconsidering “sending their kids north to Ivy League universities, subscribing to Northern publications, or hiring Yankee tutors for their children,” as journalist Jenny Jarvie notes. And now, as tensions flared further, they also began to reject the celebration of Thanksgiving.

And yet, this did not deter Sarah Josepha Hale, who should be remembered as American history’s most tireless advocate for a national celebration of the holiday. Hale’s 1827 novel Northwood: Or, Life North and South, was among the earliest American novels to offer even a cursory criticism of slavery; while her books have been mostly forgotten these days, her poetic composition “Mary Had a Little Lamb” remains a popular grammar-school banger today. In any case, the author rose to become editor of two of the country’s most prominent magazines, and in their pages, Hale waxed poetic about the need for a shared day of gratitude and moral reflection. Her campaign also included letters written to presidents and yearly missives pleading her Thanksgiving case to every state governor. But as the Civil War dawned, responses from soon-to-be Confederate states were often chilly. Virginia governor and enslaver Henry Wise groused in his 1856 response to Hale that the “theatrical national claptrap of Thanksgiving ha[d] abided other causes,” meaning the governor believed the day had been used to spread abolitionism.

By now, Southerners even found Thanksgiving foodstuffs suspicious. In Hale’s novel Northwood, she had described pumpkin pie as “an indispensable part of a good and true Yankee Thanksgiving; the size of the pie usually denoting the gratitude of the party who prepares the feast.” Pumpkins were grown on New England’s small farms, the symbolic opposite of the sprawling Southern plantations that served as labor camps for so many Black enslaved people. Those Northerners who ate pumpkin, according to Cindy Ott, author of Pumpkin: The Curious History of an American Icon, were engaging in a form of identity politics—“a way to affirm New Englanders’ identity through attachments to a place, a particular landscape, and the simple virtues of farm life.” And thus, the South even held pumpkin pie as an expression of anti-slavery sentiment, or what might be termed “virtue signaling” in today’s parlance. What’s more, since most of the South’s cooking was actually done by Black enslaved women, and sweet potatoes were similar in every way to the yams of West Africa, sweet potato pie was the South’s more popular dish. That remains true at both Black and white Southern Thanksgivings.

Hale lucked out in 1863, when more than 35 years into her campaign, President Abraham Lincoln finally cosigned the idea of an annual national Thanksgiving. Nine months after the Emancipation Proclamation, in a decree dated October 3, Lincoln designated “the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving.” That declaration did little to promote national unity, coming as it did amid the churn of the Civil War. But after the South’s defeat two years later, the December 8, 1865, edition of The New York Times carried the reprint of a sermon by Manhattan Presbyterian minister James Renwick Wilson. It was titled, “The Abolition of Slavery the Chief Cause for Thanksgiving.”

“The great blessing that has flowed to us from the late conflict is the destruction of slavery; it was only desirable that the Union should be preserved and the government saved, that it might be the defender of liberty,” the sermon read. “The war has been worth all that it cost the nation; the sacrifice has been great, but the benefit greater. How great a cause of thankfulness we have in the destruction of this wickedness, those only can realize who have formed a true conception of the system, and of its far-reaching and destructive influence. The war has taught the nation a lesson which it was slow to learn, but taught it effectually.”

But even after the war’s end, the South—or rather, the white South—continued to abstain from celebrating Thanksgiving. As activist Dan Morrison writes, “only after Black people were betrayed with the downfall of Reconstruction and white unity once again prevailed” during the era known as Reconciliation did white Southerners “celebrate Thanksgiving along with their Northern white cousins.” And even that took decades. For example, in 1868, Texas’s Austin State Gazette suggested that the day be ignored, since it was a celebration of “Reconstruction, the 14th amendment and nigger voting.” Texas Governor O.M. Roberts, an ex-Confederate officer, called it a “damned Yankee institution” in the late year of 1879. Black people and white Republicans celebrated the day, nonetheless. In 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed a bill that moved Thanksgiving to the fourth Thursday in November.

So what of the more familiar popular myth of Thanksgiving—the one in which faceless Indians “welcome the Pilgrims to America, teach them how to live in this new place, sit down to dinner with them and then disappear,” to quote Dan Silverman, author of This Land Is Their Land? Puritans were associated with New England, and the North more broadly, and Southerners were loath to include mention of them even as Thanksgiving picked up steam below the Mason-Dixon Line. The First Thanksgiving author Robert Tracy McKenzie writes that “long after the Civil War, most artistic representations of Thanksgiving that included Native Americans portrayed them as openly hostile, and it is no coincidence that the now familiar image of Indians and Pilgrims sitting around a common table dates from the early 20th century.” Silverman emphasizes that the Pilgrims and Indians story gained traction as white Protestants, status-insecure in the face of waves of immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century, sought a way to reassert cultural dominance. And here we are.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

A few years ago, Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton—who calls slavery a “necessary evil” and more than once has advocated murdering protesters—complained that Thanksgiving was being undermined by “revisionist charlatans of the radical left.” Cotton, like the rest of the right-wing chorus singing this tune, was actually confessing his deep, seemingly infinite ignorance. The real revisionism of Thanksgiving’s history isn’t in acknowledging the truth of colonial violence but in whitewashing the abolitionist politics that once defined the day. The most historically faithful way to recognize that history, too long ignored, is by highlighting those radical roots. This year, let’s honor tradition by once again making Thanksgiving radical.

More from The Nation

The settlers who arrived in Plymouth were not escaping religious persecution. They left on the Mayflower to establish a theocracy in the Americas.

Alice had the ability to look to the future and a world where laws and attitudes did not keep disabled people poor, pitied, and isolated.

First of all, in order to ask questions about the young women he preyed on, they’d need to see them as people.

Jessica Adams was barred from teaching a course on social justice for six weeks after showing a graphic that listed MAGA and Columbus Day as forms of “covert white supremacy.”

An interview with the author of a new book documenting the brutalities of childbirth in the post-Dobbs era.