The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?

Italian painter Primo Conti drawing from life a portrait of Italian writer and dramatist Luigi Pirandello. Italy, 1920s

(Mondadori via Getty Images)

At the height of his prominence, Luigi Pirandello was the principal darling of Italian drama. His plays were performed throughout Europe and the United States; Mussolini threw 700,000 lire at him when he decided to found an arts theater in Rome; and he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934, praised for his “bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art.” His acclaim was widespread: Jean-Paul Sartre hailed him as the most timely modern dramatist of the 20th century. And when Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot premiered in 1953 in Paris, the writer Jean Anouilh estimated that the evening at the Babylone Theater was “as important as the first Pirandello produced by [George] Pitoëf in Paris in 1923.” Jorge Luis Borges felt a great kinship with him; Thomas Bernhard namechecked him. How, then, did Pirandello end up a half-forgotten castaway of European letters by the 1980s? The answer, in part, appears straightforward: Pirandello was a fascist.

Books in review

One, None, and a Hundred Grand

Pirandello’s work betrayed a fascination with violence and its supposed power to cleanse society, and he approached his art with the attitude of giving form to chaos. His writing was popular, though, because of his highly developed style, which was characterized by a ceaseless desire to understand the world from the standpoint of the individual. Pirandello was startlingly modern: He committed himself to an ironic self-consciousness, to creating characters that struggled impossibly for individual freedom and to live up to their ideals. He cast off the romanticism, sensuality, and religiosity of art’s past in exchange for earnest, cold intellect. And though he used this artistry to glorify a mythic, heroic, and authoritarian Italian past, this did little to diminish, at least for a while, the appeal of Pirandello’s proto-existentialism. He was simply too masterful at both expressing the fractured mentality of the 20th-century man and critiquing what that mentality had wrought for society.

But his appeal did diminish. And Pirandello’s fascism is perhaps why, today, his readership in North America is sparse. Scattered translations of his work come and go with perhaps a review but little fanfare. Nearly 100 years after his death, Pirandello’s work doesn’t so much travel across the Atlantic as it hitches a ride by way of his successors. Yet the question does remain: What is to be made of Pirandello’s peculiar mix of fascist existentialism? And should we seriously consider its influence?

A recent reissue of Pirandello’s One, None, and a Hundred Grand (translated by Sean Wilsey) offers a new opportunity to answer these questions. The 1925 novel, written over the course of 15 years and published a year after the author’s declaration of fealty to fascism, is quintessential Pirandello. An endlessly psychological examination of the pathetic heroics of a lone-wolf vigilante, One, None, and a Hundred Grand represents a perfect example of the antagonisms that both fuel and complicate his work. It gives a window into the mind of a writer who glorified violence but never committed it, who lived vicariously through his family and his art to have a taste of the heroic life. Pirandello never joined the Italian Blackshirts, but he did pose in their costume. He considered enlisting in World War I, then didn’t. But for American readers today, Pirandello’s type—the bellows of a straw man dressed in general ceremony—is a familiar figure. He may be forgotten or unknown, but his writing importantly cataloged the broken psychologies of a dysfunctional society left adrift. Perhaps for this reason, Pirandello still has something to offer the contemporary reader.

The heroism of strong men enamored the Pirandello family: Luigi’s grandfather helped organize the anti-Bourbon insurrection of 1848 in Palermo; his father fought Bourbon troops alongside Garibaldi in the same city 12 years later; his uncles marched and fought with the general as far as Naples on the road toward Italian unification. When Luigi was born in 1867, on the island of Sicily, in the town of Agrigento, the path laid before him seemed almost predetermined. He was a vociferous nationalist who preferred the gun over the ballot box. And there was one familial code that seemed as natural as breathing: that glory could only be gained through vigorous and violent action. Pirandello never lost faith in those values, only in the men who failed to live up to them.

He had been born into an Italy making its final, ecstatic push toward unification. But Pirandello came of age watching that Italy devolve into political scandal, corruption, and infighting. The Banca Romana was found to be giving interest-free loans to leading politicians so they could fund their elections and bribe local newspapers; the Sicilian peasant leagues were crushed by the Crispi government; a trade war with France crippled agricultural markets and sent many into ruin. These developments disgraced the entire political system. And they left Pirandello lamenting Italy’s loss of Garibaldian direction. Even his family, he soon realized, had abandoned their commitments. He discovered his unmarried uncle living with a woman—a singer with a scandalous reputation—who filled the house with a rotating cast of friends, parrots, and pet monkeys. Pirandello was aghast: The uncle represented for him an entire older generation of heroes who had retreated from power and politics into a ruinous “irregular life.”

It was the impossible struggle to live up to one’s ideals that would define Pirandello. “What has become of man?” he wrote in a 1893 article. “What has this microcosm, this king of the universe become?” He would spend his career wrestling with that question across his many short stories, plays, and novels, writing characters who struggle, and often fail, to manifest a world in their personal image. And while he wrote, he waited for a great hero to bring glory back to Italy. When he finally found him, Pirandello devoted himself to him.

The man was Benito Mussolini. Pirandello’s enthusiasm for “Il Duce” and the Fascist political machine he rode into power in 1922 was unbridled—even after 1924, when Mussolini’s deputies, a group of ex–World War I soldiers led by Amerigo Dumini, abducted the Socialist politician Giacomo Matteotti and stabbed him to death with a carpenter’s file, throwing the Fascist movement into crisis. At that critical moment, most liberal sympathizers abandoned the regime. The Blackshirts disappeared from the streets and began to hide their party badges. A few dozen Fascist deputies considered asking Mussolini to resign as prime minister. Pirandello took a different direction: “I feel this is the most propitious moment for me,” he wrote in a public letter to Mussolini. “If Your Excellency finds me worthy to join the Partito Nazionale Fascista, I will consider it the greatest honor to become one of your humblest and most obedient followers. With utter devotion.” One year later, in 1925, Pirandello’s final novel, One, None, and a Hundred Grand, began appearing in the magazine Fiera Letteraria in serialized form.

In 1893, Pirandello had asked what had become of man. That abstract question was made more literal by his own circumstances: What had happened to the Italy of Garibaldi, the Risorgimento, armed insurrection, popular war, the Expedition of a Thousand? Those men, and that world, had been lost. For Pirandello, what Italy was left with was Vitangelo Maggot. Intensely self-conscious and isolated, a usurious banker whose heroics occur only inside his head, he is the hero of One, None, and a Hundred Grand. And the novel documents his very modern pursuit: to discover—to locate, conquer, and govern—not a nation, but his whole and singular self.

Like so many of Pirandello’s subjects, Vitangelo is something of a 20th-century Don Quixote, utterly convinced of the honor, valor, and glory of his absurd mission. But where Quixote charges at windmills, Vitangelo will fight (mostly) with himself, inside his own head, by interrogating his paralyzing, schismatic mind. Pirandello uses the toolkit of modernist fiction and its fixation on interiority to demonstrate the foolishness of modernity itself, and to lament the damages it has perpetrated on once-heroic man.

The novel’s protagonist is a far cry from the Garibaldian conqueror, a hero who enacts great deeds through the body. Vitangelo is afraid and suspicious of the outside world, someone who sees his mind as essentially severed from it. He is a man who sees his body not as a vehicle for great deeds but as inherently “worthless, a lot of nothing.” So when, on the first page, Vitangelo is told by his wife that his nose is crooked, this material observation causes Vitangelo’s entire sense of his metaphysical self to collapse. What’s a man to do, having lived 28 years blind enough to believe that his nose was, “if not beautiful, at least wholly inoffensive”? This man, at least, sets off on a philosophical quest to find the answer to that question. “If I wasn’t the man I imagined myself to be in the eyes of others, then who was I?” Vitangelo asks. He realizes suddenly that he is not one person but multiple people: one man to himself, and a hundred thousand men to a hundred thousand different others. This requires only one course of treatment: “I intended to discover who I was in the eyes of the people who were closest to me, my so-called intimates,” Vitangelo explains, “and, at a minimum, take spiteful pleasure in destroying this person in their eyes.”

Vitangelo comes to the conclusion that the mind itself must be the problem, and that the way to reconcile the chaos of his inner life is through externalized brutality. Vitangelo must create a unified self, in the same manner that Garibaldi had created a unified Italy. Garibaldi had mustered the violence and courage of a thousand men to fight for a single goal. Vitangelo, in his respective world, must do the same. “Do you want to live?” Vitangelo asks himself. Or, as the original Italian has it: “Do you want to be?” That is: Do you want to have a whole self? Do you want to give form to chaos? Then you must act upon the world, and make it your own.

Despite the grandeur of his thinking, Vitangelo’s philosophical quest quickly devolves into a pitiful one. (Pirandello’s assertion seems to be that you can take the man out of the modern, but you cannot take the modern out of the man.) Vitangelo evidently confuses heroic action with acting like a jackass. He prowls into the bank—where he is majority owner—and viciously insults his business partner, Sly, by telling him his wife should be “locked up in the madhouse.” He evicts a local character named Marco Godson who has been living rent-free in one of his properties, waits until the last of Godson’s possessions is tossed out into the street, and then announces that he has signed the deed of the house over to Godson, giving it to him for free. He tries talking with his dog and kicks it after it sneezes. It’s wretched. He can’t help but contemplate suicide.

When each of these acts fails to make Vitangelo whole, he goes to greater and more desperate lengths to accomplish his goal of self-unification, destroying his life and the lives of his closest friends and family in the process. He liquidates the bank, abandons his wife, shacks up with a different woman (that is, until she shoots him with a revolver). Nothing works. “How did I not understand that the usurer Vitangelo Maggot could go mad but could never be destroyed?” he despairs. Having failed to become a Garibaldian hero, Vitangelo renounces society and the material world entirely in a spiteful religious conversion. To achieve the existential freedom he so desperately desired, Vitangelo resigns himself to an external authority—in the form of God and the church. If before he’d thought too much, if thinking had been the paralyzing problem, now he has no need for thinking: His renunciation “prevent[s] thought from beginning to spin and build vain, empty constructions within me.” And if before he sought to solve his problem by acting upon the external world, now the action occurs within him: “I am dying all the time; I am, in every moment; and then I’m born again: alive and alone, without memories, uncontained, complete.”

Ultimately, One, None, and a Hundred Grand is a novel about the violent antagonisms of the self, and a novel that contains violent antagonisms. It is told in myriad labyrinthian digressions, rendered with cold precision and jerky prose. It glorifies individual freedom and yet laments our collective incapacity to ever achieve it, and how we are bound instead to corrupt and debase the ideals we fight so frantically for. The world of Garibaldi is gone; modern man—pitiable, weak, self-conscious—cannot ever hope to re-create it. What the world needs, Pirandello concludes, is direction. Vitangelo needs the church, the novel its novelist, the play its director, the people its “great captain,” as Pirandello once wrote, to lead the nation forward. It is no wonder Pirandello dubbed Mussolini the “artist of the Italian nation.”

The critic Guy Davenport once wrote that Ezra Pound’s great achievement was to take the best of the past and pass it on. That is the ostensible task for readers of One, None, and a Hundred Grand. What readers are tasked to leave behind is obvious enough: the fascism, Pirandello’s contemptuousness, his misogyny. (It bears mentioning that Vitangelo addresses his readers repeatedly and exclusively as “signori,” gentlemen, though Wilsey scrubs these entirely and gives us the appropriately genderless “you,” or “readers.”) What makes the task especially difficult is that those fascistic qualities are not incidental to Pirandello’s work but rather inherent in it. They damage its appeal and its staying power. Moreover, the great revelation of Pirandello’s work is not a revelation at all for the contemporary reader. Vitangelo goes mad from realizing he is multiple men to multiple people, from admitting there is no singular truth and that truth itself may not even exist. But today we are bombarded by the multiplicity of our selfhood. Fragmentation is simply our standard way of life. Vitangelo’s struggle reads as a quaint historical curiosity.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

There are elements of Pirandello’s work that readers may find worth keeping. His contribution to European letters was certainly important: He wrestled with the absurdity of life and the self with the probing skill of a trained philosopher; he is, at many times, very funny. Broadly speaking, if there is something Pirandello can offer us, it is to help us recognize that we are living in his world, and—despite what we might hope—living among fascists, not to mention self-conscious and murderous vigilantes steeped in disaffection and irony. Pirandello may not answer any new or novel questions about our problems of living, or quell our contemporary existential anxieties. But he can help us grasp how one single, difficult question—who am I?—can send a person spiraling, can make them desperate enough to destroy a life. Theirs, perhaps, but more often someone else’s.

I know that many important organizations are asking you to donate today, but this year especially, The Nation needs your support.

Over the course of 2025, the Trump administration has presided over a government designed to chill activism and dissent.

The Nation experienced its efforts to destroy press freedom firsthand in September, when Vice President JD Vance attacked our magazine. Vance was following Donald Trump’s lead—waging war on the media through a series of lawsuits against publications and broadcasters, all intended to intimidate those speaking truth to power.

The Nation will never yield to these menacing currents. We have survived for 160 years and we will continue challenging new forms of intimidation, just as we refused to bow to McCarthyism seven decades ago. But in this frightening media environment, we’re relying on you to help us fund journalism that effectively challenges Trump’s crude authoritarianism.

For today only, a generous donor is matching all gifts to The Nation up to $25,000. If we hit our goal this Giving Tuesday, that’s $50,000 for journalism with a sense of urgency.

With your support, we’ll continue to publish investigations that expose the administration’s corruption, analysis that sounds the alarm on AI’s unregulated capture of the military, and profiles of the inspiring stories of people who successfully take on the ICE terror machine.

We’ll also introduce you to the new faces and ideas in this progressive moment, just like we did with New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani. We will always believe that a more just tomorrow is in our power today.

Please, don’t miss this chance to double your impact. Donate to The Nation today.

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Imprisoned and censored by his home country of Iran, the legendary director discusses his furtive filmmaking.

The economic force is often seen as a barometer for a nation's mood and health. But have we misunderstood it all along?

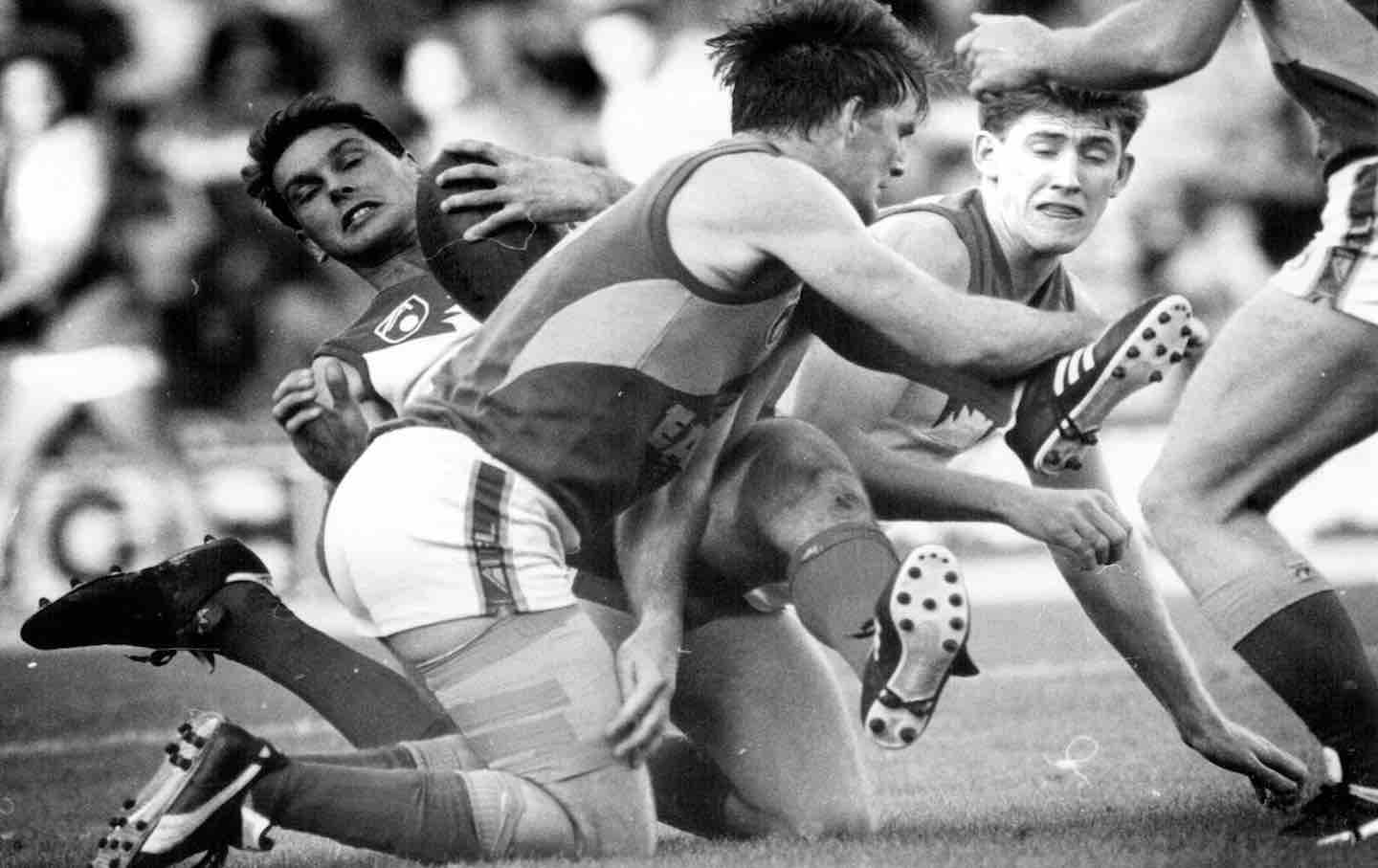

In The Season, Helen Garner considers the zeal and irrationality of fandom and her country’s favorite pastime, Australian rules football.