More than 400 years ago, English colonist and explorer John Smith wrote in his diary that there were indigenous villages along a major river in what is now Virginia. But reports of the villages' location were later forgotten and their existence disputed.

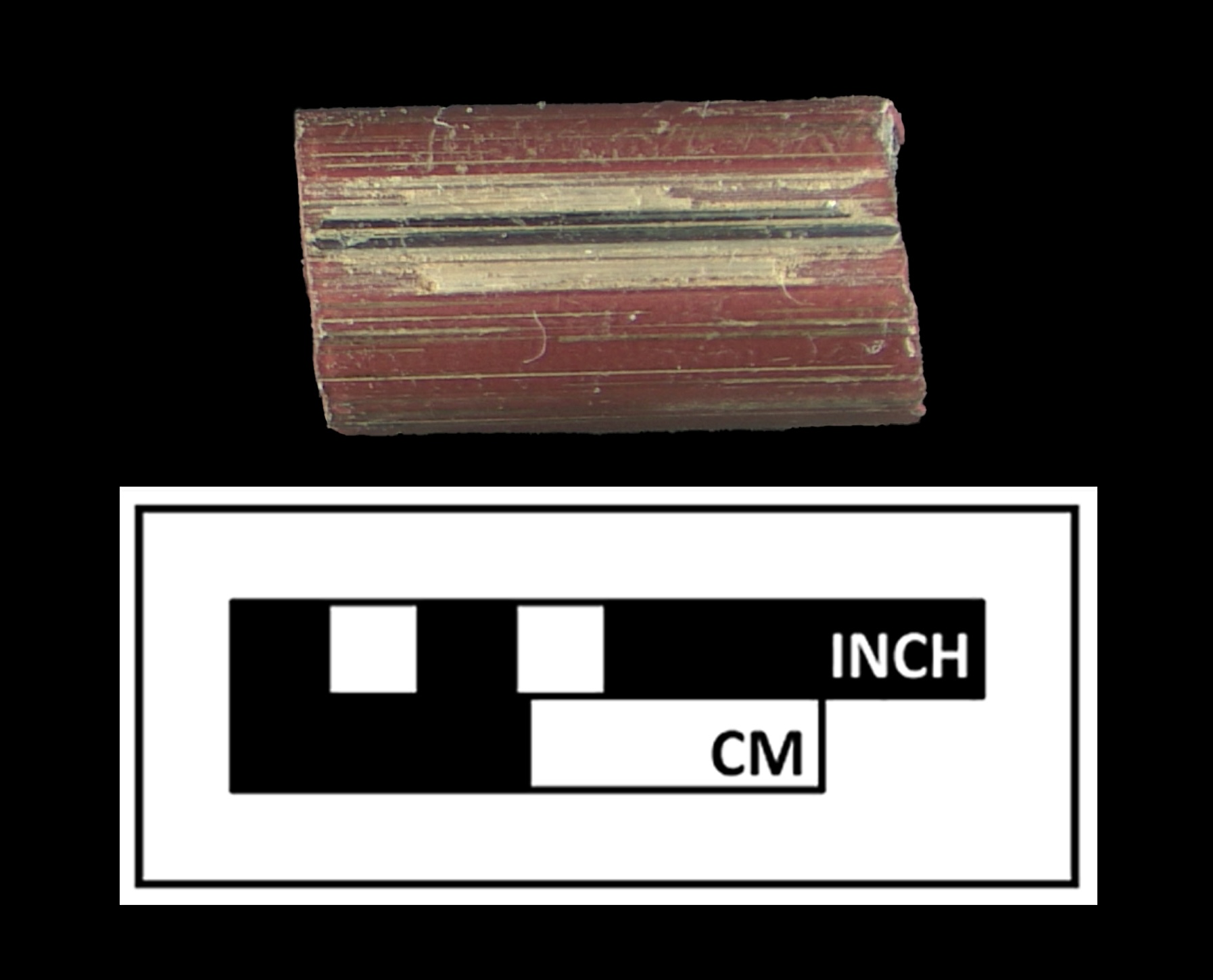

Now, archaeologists excavating along the Rappahannock River have uncovered thousands of artifacts, including beads, pieces of pottery, stone tools and tobacco pipes, that they believe come from the villages Smith described centuries ago.

The main part of the river is surrounded by high cliffs that would allow only limited access to the village above, King said. But from the heights of the village there would be views of the entire river valley, and the soil at the site would be good for growing corn, King told Live Science by email.

The river is named for the Rappahannock Tribe, one of 11 Native American groups recognized in Virginia. Many tribal members still live nearby and hope to reclaim and protect ancestral lands along the river, King said.

Stories of the Rappahannock

Smith was a mercenary and adventurer in Europe before he was elected president of the council on Jamestown Colony in Virginia in 1608. (Jamestown had been founded the previous year and is recognized as the first permanent English settlement in North America.)

Smith was a self-aggrandizing figure and left behind an “incredible” legend, including his supposed love story with Pocahontas. His letters and witness statements indicate that Smith introduced military discipline to Jamestown, where he famously declared that “he who will not work shall not eat”—a policy credited with saving the colony from famine in its early years, although more than 400 Jamestown colonists died of starvation after John Smith returned to England in 1609.

King said Smith was an avid explorer who spent weeks mapping the Rappahannock River and wrote about Native villages in the area that became the Fones Cliffs area.

The new findings also fit oral histories of the Rappahannock Tribe, King said.

“Oral history gets a bad rap in some circles because memories aren't perfect, but neither are documents,” she said. “The strategy is to read both the gist and the gist of both sources and question everything.”

King and her colleagues have been researching the early history of the Rappahannock River region for several years. They located the Fones Cliffs settlements by comparing historical documents with oral histories and “walking the land,” she said.

So far, researchers have unearthed around 11,000 Indigenous artefacts at two sites in Fones Cliffs, and some may date back to the 1500s.

Land claims

According to Smith's writings, in the 17th century the Rappahannock Tribe agreed to sell about 25,000 acres (10,100 hectares) of land in the Jamestown Colony for the price of 30 blankets, beads and some tools. However, land deals like this between Europeans and Native Americans are often discussed by historians. For example, it is unclear whether Native Americans understood the “sale of land” in the same way as Europeans did at the time; they may have perceived such land transactions as “sharing” or “renting” the territory, researchers previously reported Living science.

The new artifacts could have implications for the region's development, King said.

“The Rappahannock people consider the great river valley their homeland, regardless of who owns the land today,” she said. So the tribe is working with private partners and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to acquire or otherwise protect key areas.

New York University historian Karen Ordahl Kuppermanexpert on Smith and early Jamestown who was not involved in the discoveries, told Live Science in an email that Smith checked his map with the Chesapeake Algonquian people who accompanied him on his expedition.

“Important finds like this are the result of archaeologists collaborating with modern-day indigenous peoples like the Rappahannock,” she said.

David Priceindependent historian and author “Love and Hate in Jamestown: John Smith, Pocahontas and the Beginning of a New Nation(Vintage, 2005), who was not involved in the research, called the newly discovered artifacts “miraculous finds.”

“They deepen our knowledge of the Rappahannock and their interactions with the English,” he told Live Science, “especially during the early fragile years of English exploration, when Native communities and settlers shaped each other's histories through trade, diplomacy and conflict.”