Fergus WalshMedical editor

A group of blind patients can now read again after receiving a life-changing implant at the back of their eye.

A surgeon who inserted microchips into five patients at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London says the results of an international study are “astonishing”.

Sheila Irvine, 70, who is registered blind, told the BBC that being able to read and do crossword puzzles again was “out of this world”. “It’s beautiful, wonderful. It gives me so much pleasure.”

The technology offers hope for people with an advanced form of dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) called geographic atrophy (GA), which affects more than 250,000 people in the UK and five million people worldwide.

In people with this disease, which is more common in older people, cells in a tiny part of the retina at the back of the eye gradually become damaged and die, resulting in blurred or distorted central vision. Color and fine details are often lost.

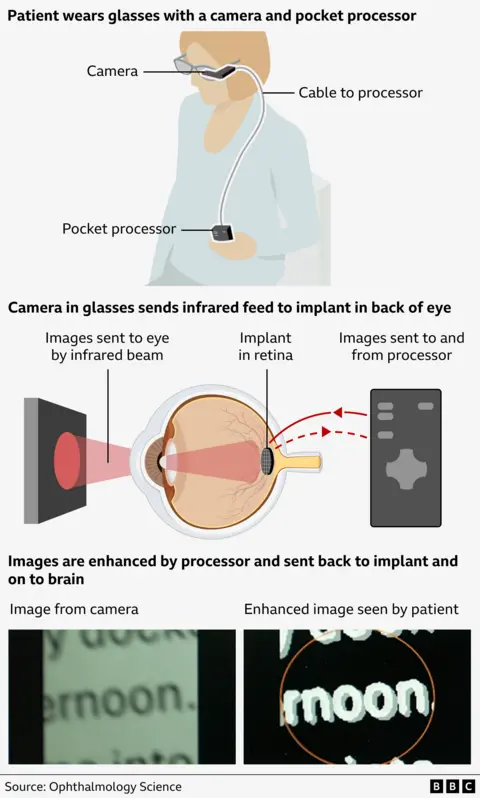

The new procedure involves inserting a tiny photovoltaic microchip, 2 mm in area and about the thickness of a human hair, under the retina.

Patients then wear glasses with a built-in video camera. The camera sends an infrared beam of video images to an implant at the back of the eye, which sends them to a small handheld processor for enhancement and clarity.

The images are then sent back to the patient's brain through the implant and optic nerve, restoring some vision.

Patients spent months learning to interpret the images.

Mahi Mukit, a consultant surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London who led the UK arm of the study, told the BBC it was “ground-breaking and life-changing technology”.

“This is the first implant that has been demonstrated to give patients meaningful vision that they can use in their daily lives, such as reading and writing.

“I think this is great progress,” he said.

How does implantation technology work?

For research published in New England Journal of Medicine38 patients with geographic atrophy in five European countries took part in a study of the Prima implant, which is manufactured by the California Biotechnology Science Corporation.

Of the 32 patients who received the implant, 27 were able to read again using central vision. After a year, this equated to an improvement of 25 letters, or five lines, on the eye chart.

For Sheila from Wiltshire the improvement is even more dramatic. Without the implant, she cannot read at all.

But when we filmed Sheila reading a medical record at Moorfields Hospital, she didn't make a single mistake. Once completed, she punched the air and applauded.

“I'm a lucky bunny”

The task required enormous concentration. Sheila had to place a pillow under her chin to stabilize the image from the camera, which can only focus on one or two letters at a time. At some points she needed the device to be switched to magnification mode, especially in order to distinguish between the letters C and O.

Sheila began losing central vision more than 30 years ago due to loss of retinal cells. She describes her vision as having two black discs in each eye.

Sheila walks with a white cane because her very limited peripheral vision is completely blurred. On the street, she cannot read even the largest street signs.

She said when she had to give up her driver's license, she cried.

But since having the implant fitted about three years ago, she, along with the medical team at Moorfields, has been very pleased with her progress.

“I can read my posts, books, crossword puzzles and Sudoku,” she says.

When asked if she ever thought she would read again, Sheila replied, “Not necessarily!”

“This is amazing. I’m a happy bunny,” she adds.

“Technology is moving so fast, it’s amazing that I’m a part of it.”

Sheila does not wear the device outside. Part of this is because it requires a lot of concentration: she has to keep her head still to read. She also doesn't want to become overly dependent on the device.

Instead, she says she “rushes through her chores” every day before sitting down and putting on her special glasses.

The Prima implant has not yet been licensed, so is not available outside of clinical trials, and it is unclear how much it might ultimately cost.

However, Mahi Mukit said he hoped it would be available to some NHS patients “within a few years”.

It is possible that in the future this technology could be used to help people with other eye diseases.

Dr Peter Bloomfield, director of research at the Macular Society, says the results are “encouraging” and “fantastic news” for those who currently have no treatment options.

“Artificial vision can offer hope to many, especially after previous disappointments in the world of dry AMD treatment.

“We are now closely monitoring whether the Prima implant will be approved for use here in the UK and, crucially, whether it can be made available on the NHS.”

The trial is not expected to help people with conditions in which the optic nerve, which sends signals from the retina to the brain, does not function.