Chris BaraniukTechnology reporter

Except

ExceptLying on your back in a large hospital scanner, as still as possible, with your arms above your head – for 45 minutes. This doesn't sound like much fun.

This is what patients at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London had to do during certain lung tests until the hospital installed a new device last year that cut the time for these tests to 15 minutes.

This is due in part to the scanner's imaging technology, as well as a special material called cadmium zinc telluride (CZT), which allows the machine to create highly detailed 3D images of patients' lungs.

“With this scanner, you get beautiful images,” says Dr. Kshama Vechalekar, head of nuclear medicine and PET. “This is an amazing feat of engineering and physics.”

The CT in the device installed at the hospital in August last year was manufactured by the British company Kromek. Kromek is one of the few companies in the world that can produce CZT. You may never have heard of this material, but according to Dr. Vechalekar, it is “revolutionizing” medical imaging.

This wonder material has many other uses, such as in X-ray telescopes, radiation detectors and airport security scanners. And it is becoming more and more in demand.

The studies of patients' lungs carried out by Dr Vechalekar and her colleagues include looking for the presence of many tiny blood clots in people with long Covid or, for example, a larger clot known as a pulmonary embolism.

The £1 million scanner works by detecting gamma rays emitted by a radioactive substance that is injected into patients' bodies.

But the sensitivity of the scanner means less of this substance is needed than before: “We can reduce doses by about 30%,” says Dr. Vechalekar. While CZT-based scanners in general are not new, large full-body scanners such as this one are a relatively recent innovation.

Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust

Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation TrustCZT itself has been around for decades, but its production is very difficult. “It took a long time for this to develop into an industrial-scale manufacturing process,” says Arnab Basu, founding executive director of Kromek.

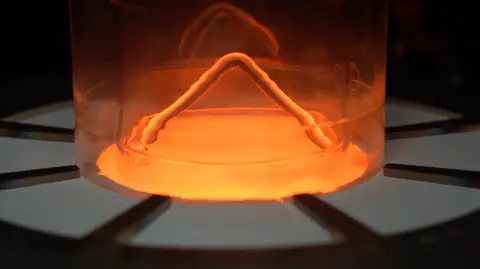

At the company's Sedgefield facility, a room contains 170 small ovens that Dr Basu says look “like a server farm”.

In these furnaces, a special powder is heated, melted, and then solidified into a monocrystalline structure. The whole process takes weeks. “Atom by atom, the crystals are rearranged […] so they all become consistent,” says Dr. Basu.

The newly created CZT semiconductor can detect tiny photonic particles in X-rays and gamma rays with incredible precision—like a highly specialized version of the light-sensitive silicon image sensor in your smartphone camera.

Whenever a high-energy photon hits the CZT, it mobilizes an electron and this electrical signal can be used to create an image. Earlier scanning technology used a two-step process that was not as accurate.

“It’s a digital device,” says Dr. Basu. “This is one stage of transformation. It stores all the important information such as time, energy of the X-rays hitting the CZT detector – you can create color or spectroscopic images.”

He adds that CZT-based scanners are currently used to detect explosives at UK airports and to scan checked baggage at some US airports. “We expect CZT to enter the carry-on segment next year. [few] years.”

Except

ExceptBut getting CZT is not always easy.

Henryk Krawczynski from Washington University in St. Louis, USA, has used this material before. on space telescopes attached to high-altitude balloons. These detectors can detect X-rays emitted by both neutron stars and the plasma around black holes.

Professor Krawchinsky requires very thin 0.8mm thick pieces of CZT for his telescopes because it helps reduce the amount of background radiation they pick up, providing a clearer signal. “We would like to buy 17 new detectors,” he says. “It’s very difficult to get those thin ones.”

He failed to receive CZT from Kromek. Dr. Basu says his firm is currently in high demand. “We support a lot of research organizations,” he adds. “It’s very difficult for us to do a hundred different things.” Each study [project] you need a very specific detector design.”

For Professor Krawchinsky this is not a crisis – he says he could use for his next mission either CZT, which he has from previous research, or cadmium telluride, an alternative.

However, there are more serious headaches at the moment. The upcoming mission was due to leave Antarctica in December, but “all dates are changing”, says Professor Krawczynski, due to US government shutdown.

Diamond light source

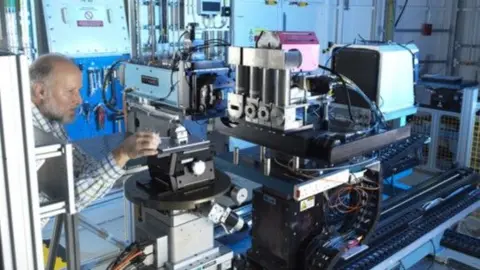

Diamond light sourceMany other scientists use CZT. Large in the UK Diamond light source upgrade A half-billion pound research center in Oxfordshire will improve its capabilities with the installation of CZT-based detectors.

The diamond light source is a synchrotron that shoots electrons around a giant ring at almost the speed of light. Magnets cause these whistling electrons to lose some energy in the form of X-rays, which are funneled away from the ring in beams so they can be used to analyze materials, for example.

Some recent experiments have involved studying impurities in aluminum during its melting. A better understanding of these impurities can help improve recyclable forms of the metal.

Following the Diamond Light Source upgrade, due to be completed in 2030, the X-rays produced will become significantly brighter, meaning existing sensors will not be able to detect them properly.

“There’s no point in spending all this money on upgrading these facilities if you can’t detect the light they emit,” says Matt Veale, detector development team leader at the Science and Technology Council and member of Diamond Light Source.

This is why CZT is the material of choice here too.