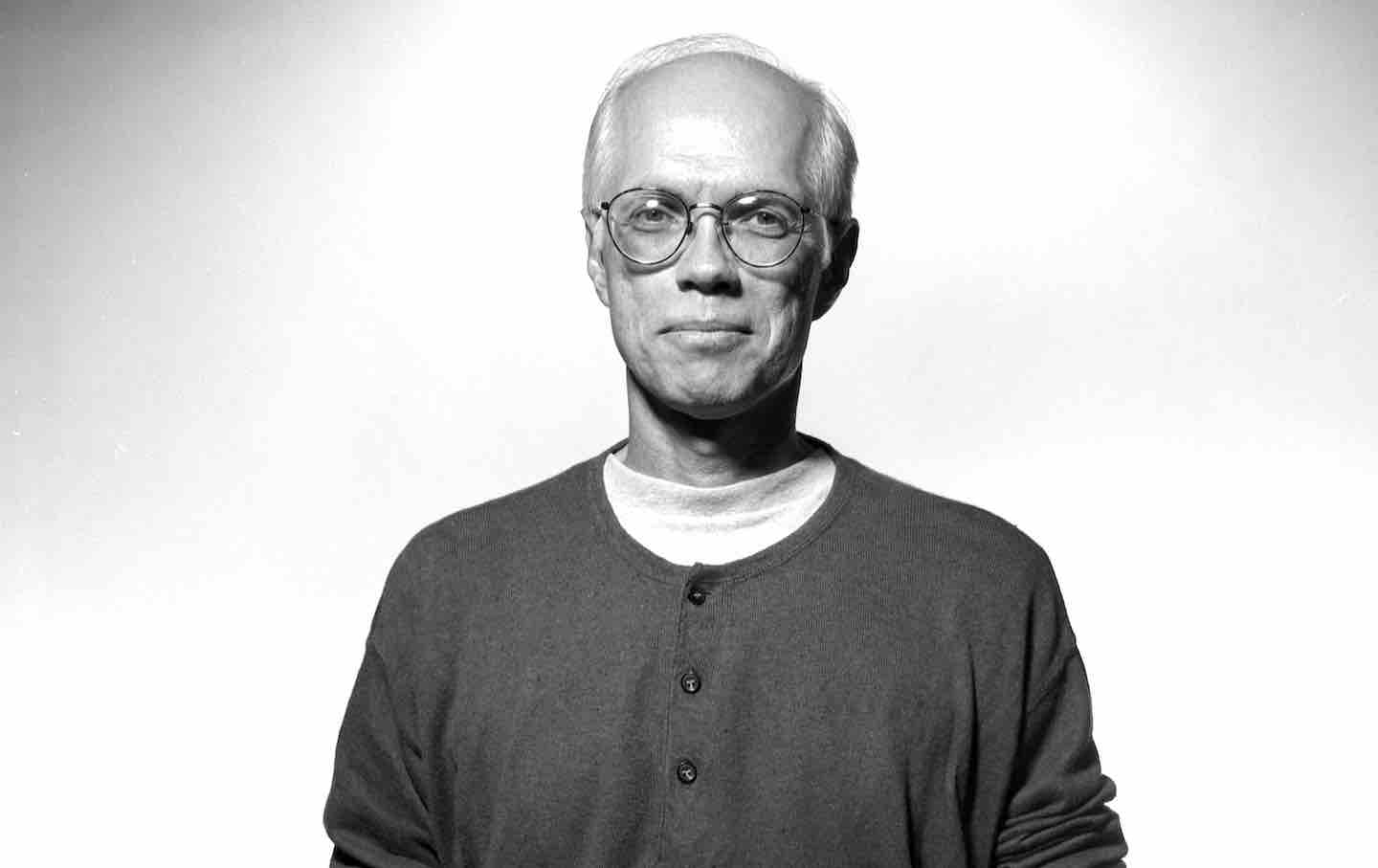

A conversation with Osita Nwanevu about the fatal flaws of our governing system, the need for a more egalitarian political economy, and his new book The Right of the People.

There is no shortage of books devoted to the crisis of democracy that have appeared since Trump’s election in 2016. But very few of these works cut to the quick and ask a rather obvious question of the last decade: What if America is not a democracy at all? Do political commentators subscribe to a fundamental misunderstanding of what constitutes a democracy in America, and have we failed to grasp not only why it’s in such bad shape today but also what steps can be taken to fix the system? Osita Nwanevu’s new book, The Right of the People: Democracy and the Case for a New American Founding, is important for this very reason. Nwanevu believes that the United States has never truly been a democracy, but that doesn’t mean it cannot become one. For this to happen, according to him, would not only demand a radical reform of our political institutions—abolishing the Senate and getting rid of the Electoral College, for instance—but also transforming the American economy, which is to say that a real democracy for Nwanevu demands a certain kind of egalitarian political economy

The Nation spoke to Nwanevu why the US isn’t truly a democracy and what must be done to transform its political and economic system to become one.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: In reaction to the election of Trump in 2016, a cottage industry sprouted up in publishing devoted to the so-called crisis of democracy. The same hand-wringing remains, but its made more complicated by the fact he won a majority in 2024. Might Trump’s victories instead indicate distrust and resentment of the political personnel and institutions that are failing to deliver on the promises of democracy? In other words, maybe it’s not democracy that is being rejected per se but rather a political system that is failing to protect the power of the people.

Osita Nwanevu: People still feel good about the concept of democracy. There was an AP/NORC poll last year, for instance, that found that 90 percent of Americans believe democracy is either a good but flawed system or the greatest system of government. Only 8 percent were willing to dismiss it entirely. Whether they shared the same understanding of what democracy actually means is another matter, of course, but most people like the idea of democracy and want to feel aligned with it. It’s “American democracy” people are down on—that same poll found a 53 percent majority of Americans believing democracy here is functioning poorly, with an additional 14 percent taking my position that America really isn’t a democracy. You see that same pessimism across surveys—Gallup found 71 percent of Americans reporting dissatisfaction with how democracy in America is working last year, the highest proportion they’d ever recorded.

I think it’s suicidal to run on the defense of our institutions in that context. It’s not, as you suggest, that people who were on the fence in this last election were rejecting democracy in considering or eventually voting for Donald Trump. It’s that many Americans simply didn’t believe they had much of a democracy to lose to begin with. So they voted on other issues instead.

DSJ: I was not aware until reading your book of how many contemporary liberal thinkers are critical of democracy. Of course, for much of its history liberalism has had an uneasy relationship with democracy, but for decades the two have often been conflated, hence the idea of “liberal democracy.” Nevertheless, you show how some of today’s leading liberal pundits, such as Ezra Klein, think that democracy is to blame for how partisan and factionary the political system now is. What do you make of such liberal critics?

ON: Klein shares many, if not all of my concerns about the design of our federal system and the impact its inequities have on our politics and policymaking. He’s not against democracy, but he is troubled by the way politics can coarsen our lives and our relationships with each other—more so than I am, I think it’s fair to say. Ideological polarization and our political divisions pose important challenges for us— and people aren’t wrong to be troubled by the assassination of Charlie Kirk, for instance, or the possibility that we could see political violence continue to rise—but conflict and difference are features of democracy, not bugs. Political leaders and pundits in this country often present us with a picture of how democracy is supposed to function—if we’d only talk out our differences civilly and through reasoned argument, we’d discover we actually have more in common than our divisions suggest and should build political consensus on that basis—that’s at odds with the realities of practicing politics in a society as large and diverse as ours. It’s simply not the case that our divisions are merely illusory or just products of social dynamics or mostly the result of manipulation by bad actors, as Barack Obama suggested in his 2004 speech to the Democratic National Convention.

Political actors do like to slice and dice us apart for their own ends, yes, but we also have deep, genuine, and substantive disagreements about important issues facing the country for legitimate reasons. And it can make sense for us to be angry with each other or even to decide not to associate with each other on that basis. The task of liberal democratic governance is managing that conflict—there are rules of competition and engagement. There are rights that can never be infringed upon. Underneath that framework, we can live freely and peaceably; society holds together and moves forward. But there’s still room for vigorous competition and even partisan rancor that, frankly, I think we should understand as part of the price of our own democratic agency. There must be room in liberal democratic society for serious conflict. There must be room, even, for extremism—a stance that ought to be commonsensical given the fact that racial equality and equality for women were once extreme ideas pushed by voices at the fringes of American politics. I don’t think the self-appointed guardians of the liberal project today take any of this seriously.

DSJ: Is the Abundance movement antidemocratic?

ON: I think the Abundance movement sees democracy as a bottleneck that slows the implementation of important policies down or a roadblock that can prevent us from getting things done entirely. They’re right about certain things. The retiree who has the time and the privilege to go through a public comment process or file lawsuits to slow some affordable housing project down—this kind of thing is a problem. Is it a problem imposed by democracy? I don’t think so. It is democratic to give representatives elected freely and fairly—by a broader section of the public than those who have the time to muck around with public comment processes—the power to do what they were elected to do. An election should be understood, obviously, as community input. I don’t see this as a lesser form of democracy than direct participation, though I think there are places where getting citizens directly involved with governance makes sense.

These are complicated issues and it’s difficult to generalize about them. But I will say this. You cannot leapfrog over democratic politics. As successfully as you might be able to administratively push through some project without direct public input, the viability and stability of that project is going to depend upon public buy-in. People need to understand what you’re trying to do and why. Arguments have to be made and information has to be proffered. Otherwise, you run the risk of whatever it is you’re trying to do being undone. Federally, a version of this happened in this last election. The Biden administration had a number of very real technocratic successes. The public did not see or understand them. The administration did not explain them well. They lost. And now much of what they did has been torn apart.

DSJ: What is your definition of democracy? What, according to you, are its essential features?

ON: Democracy is a system of governance in which the governed govern. Governance isn’t given over to some king or higher class of authorities. The people who are themselves subject to governance do the governing. In other words, as Lincoln put it, a democracy is a system of governance of, by, and for the people. And you can tell whether a system is democratic if it has three basic features. The first is political equality—all who come to a collective choice should be in equal standing. There’s no privileged minority on the basis of arbitrary characteristics. If there were, this would leave the door open to some subset of the collective truly governing rather than the people as a whole. The second is responsiveness. Democracy is not a suggestion box. When people in a democracy come together to make a choice, the system responds. It might not happen directly or immediately. But a democratic system is meaningfully responsive to the governing public. The third is majority rule—the system responds to the public on a majoritarian basis. Of all the ways we might make collective decisions together—from some form of unanimity all the way through minority rule—majority rule is the decision rule consistent with the equality of participants. You don’t, again, have some privileged minority of stubborn holdouts or elites deciding everything.

DSJ: Wouldn’t this mean that the US has never been a democracy?

ON: Yes. First off, there are about 4 million Americans today who don’t have a full and equal say in federal governance, most of whom live in Puerto Rico and DC. They have representatives in Congress who can’t vote on the final passage of legislation. Federally, they are being governed but not governing themselves. Beyond that, even those of us with federal representation are represented highly unequally for arbitrary reasons. In the Senate, for instance, because of equal state representation, someone who happens to live in Wyoming, a state of fewer than 600,000 people—fewer than DC, as a matter of fact, has about 67 times the representation of someone who lives in California, a state of about 40 million people that gets the same number of senators.

We’re told in civics class that this is balanced by population-based apportionment in the House. It isn’t. The Senate alone shapes the judiciary and the executive branch, so the impact of those disparities ripple throughout the federal government, atop their obvious impact on the legislative process. We are not the only country with a malapportioned upper house. But ours is, empirically, much more unequal than the upper houses of comparable peers—so much so that I do not think we can reasonably call ourselves a democracy.

The stock conservative argument is that equal apportionment in the Senate was what the founders intended. In fact, the likes of Madison and Hamilton warned repeatedly that this was a stupid arrangement that would distort policymaking, and they were correct. The Constitutional Convention was simply forced into it by the small states. But as a matter of substance for us today, all of this is really neither here nor there. As I lay out in the book, conservatives are correct to say that the founders— Madison and Hamilton included, despite their misgivings about the Senate—did not intend for America to be a democracy. The question the book asks is: So what? If democracy is good, as I argue that it is, then America should become a democracy by reforming or eliminating the Senate eventually, and pursuing the other changes I discuss.

DSJ: You are basically calling for a major overhaul of the Constitution. People in this country, however, worship the Constitution. How do you respond to critics that think that you are an out of touch leftist? Is there any precedent, for instance, for the kind of suggestion that you are proposing, such as movements for constitutional alternatives?

ON: It’s possible because I’m living in a country where I once might have been a slave and am not, where women were once fully subjugated as inferior citizens and no longer are, and I once would have had to write these words with ink, or graphite, or at least the aid of wires and no longer do. Compared to the scale of the changes that have occurred in the last century and a half or so of American life, the idea that we might not have an Electoral College or a Senate by this century’s end seems positively trivial.

What it’ll take is further shifting the consciousness of an American public that already does not believe, as deeply as they might say they venerate the Constitution, that our political institutions are working. It’s the restorationists—the voices in the center who want us to return to a respect for those institutions and politics as usual—who are out of touch. They are losing and will continue to lose.

It will never be 2005, or 1995, or 1985 again. The American political system is not tenable. The only question is who’ll get to reshape it. Right now, the fascists are winning. This doesn’t have to be so. Countries often rework their basic institutions. Sweden rewrote its Constitution in 1974. Finland did so in 1999. We can’t expect the process of reworking ours to proceed as civilly. But we don’t have a choice. In bringing Donald Trump to power in the first place and failing so often to constrain him, our institutions have brought us to the brink of authoritarianism. They will take us the rest of the way there if we let them.

DSJ: How do you understand the relationship between democracy and economics and what economic policies do you propose that would allow for a more democratic society?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

ON: I don’t think I could have come up with a better caricature for the purposes of illustrating the impact of economic inequality on our political institutions than the spectacle of watching the wealthiest man on the planet donate $260 million—a fraction of a fraction of what he owns—to Donald Trump’s campaign for the privilege of reworking the federal government to his liking. Our politics and our economy aren’t separate spheres. They are fundamentally interconnected. And the growth of economic inequality in this country is a fundamental threat to the project of democracy. We will soon have our first trillionaires. Can ordinary people exercise a meaningful amount of control over the direction of our society with so much wealth and power in the hands of so few? I don’t think so. And I don’t think we solve that problem purely by reforming our campaign finance laws and regulating lobbying—as important as those goals are—partially because the wealthy can use their influence to prevent us from passing and enacting those policies in the first place. We have to fight inequality at the source, which means turning our attention to the basic structures of our economy.

We ought to do so not just because it protects political democracy, or merely because ordinary people will materially benefit from reducing inequality. We ought to do so on democratic grounds. We spend about a third of our lives at work. The decisions made at the firms we work for often affect us more directly, intimately, and immediately than decisions made in Washington, or our statehouses, or at City Hall. Yet we take it entirely for granted that we’re not entitled to any direct democratic agency at firms or within the economic sphere broadly speaking—beyond the hope that a political system dominated by the wealthy and corporations will succeed in regulating them in our interest. This is odd if we believe in democracy because we believe we ought to have a measure of control over the conditions that shape our lives. A worker at Starbucks can, rightfully, go to the polls every few years to have their voice heard on what American foreign policy should be with respect to Iran if they wish. But it’s a given to us that they aren’t entitled to have their voice heard or respected when it comes to how Starbucks ought to be run.

The time has come to resurrect the concept of “economic democracy” and to instantiate it by giving workers more democratic power at work. That means protecting and expanding traditional labor unions, but it also means exploring democratic governance structures, many of which are already in place in European economies, that might also build their agency, like works councils or mandating that corporations reserve seats on their boards for workers. I also argue that workers at major firms ought to be given shares in them, along with the voting rights ownership would entitle them to. All of this could go a long way towards fighting inequality for its own sake, yes, but also towards making good on democracy’s full promise as an ideal.

DSJ: There is a lot of despair on the liberal left today about the current state of American politics. You have essentially written about how democracy can be saved. What gives you such hope?

ON: We’ve had it unfathomably worse, as difficult as it may be to remember here and now. The history of this country—of the world—is bleak and bloody beyond description. Through it all, people on the left have done the work of politics with courage, determination, and an almost superhuman resolve. They politically organized people who couldn’t read or write. They faced impoverishment, abuse, and death. They had their moments of doubt and grand failures. But brick by brick, they built a better world. That’s how this works.

To give up on the promise of democracy—the project of our own emancipation as human beings—because Donald Trump won the popular vote in November or because The New York Times trots out some of the least informed and engaged voters in the electorate for us to gawk at every so often would be absurd. I have no patience whatsoever for doomsaying or recreational nihilism. It is fully irrational to believe we can’t win. We can.

More from The Nation

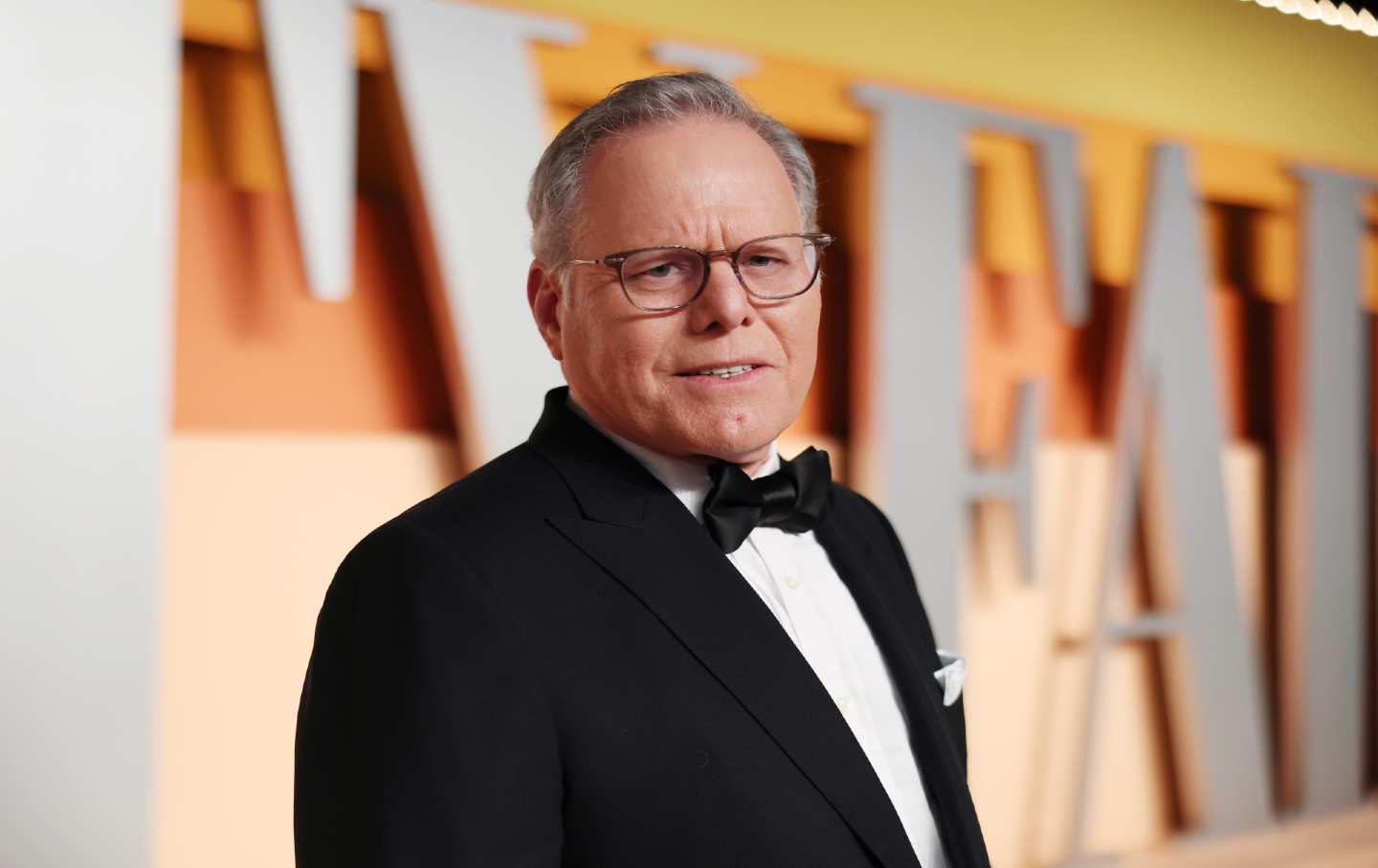

The Ellison family’s aggressive pursuit of the WBD empire would shred news values and further pillage movie and TV production.

A bowdlerized biopic of Bruce Springsteen, starring Jeremy Allen White, flattens a musician whose politics and identity are much more complicated.

Kate Folks’s Sky Daddy pokes fun at the need for love at the core of most fiction—dramatizing one woman’s quest for romance through her very literal lust for airplanes.

A conversation with the writer and theorist Jasper Bernes about the left after the summer of 2020 and the state of revolutionary politics.