WASHINGTON — A Texas redistricting case now before the Supreme Court poses a question that often divides justices: Were congressional districts drawn based on politics or race?

The answer, likely days away, could flip five congressional seats and change political control of the House of Representatives after next year's midterm elections.

Judge Samuel A. Alito, who is overseeing the appeals from Texas, set a time delay over a court ruling that called Texas's newly drawn voting map a “racial gerrymander.”

State lawyers asked for a decision by Monday, noting that candidates have a Dec. 8 deadline to file for the election.

They stated that the judges violated the so-called Purcell principle making major changes to the election map “in the middle of the candidate filing period,” and that alone warrants blocking it.

Texas Republicans have reason to be confident that the court's conservative majority will side with them.

“We begin with the presumption that the Legislature acted in good faith,” Alito wrote in a 6-3 majority last year. case in South Carolina.

That state's Republican lawmakers moved tens of thousands of black voters into or out of newly drawn congressional districts and said they did so not because of their race but because they were more likely to vote as Democrats.

In 2019, conservatives upheld partisan gerrymandering by a 5-4 vote, ruling that drawing districts is a “political matter” left to the discretion of states and their legislators, not judges.

All the justices—conservative and liberal—have said that drawing districts based on the race of voters violates the Constitution and its prohibition on racial discrimination. But conservatives say it's difficult to separate race from politics.

They also seemed willing to limit the Voting Rights Act in pending case from Louisiana.

For decades, civil rights law sometimes required states to create one or more districts that would give black or Latino voters a fair chance to “elect representatives of their choice.”

The Trump administration joined the support of Louisiana Republicans in October and said the voting rights law “has been used as a form of race-based affirmative action” that should end.

If so, election law experts have warned that Republican-led Southern states could wipe out districts home to more than a dozen black Democrats who serve in Congress.

The mid-decade Texas redistricting case should not have sparked a major legal fight because the partisan motives were so clear.

In July, President Trump called on Texas Republicans to redraw the state's 38 congressional district map to flip five seats to oust Democrats and replace them with Republicans.

At stake was control of the divided House of Representatives after the 2026 midterm elections.

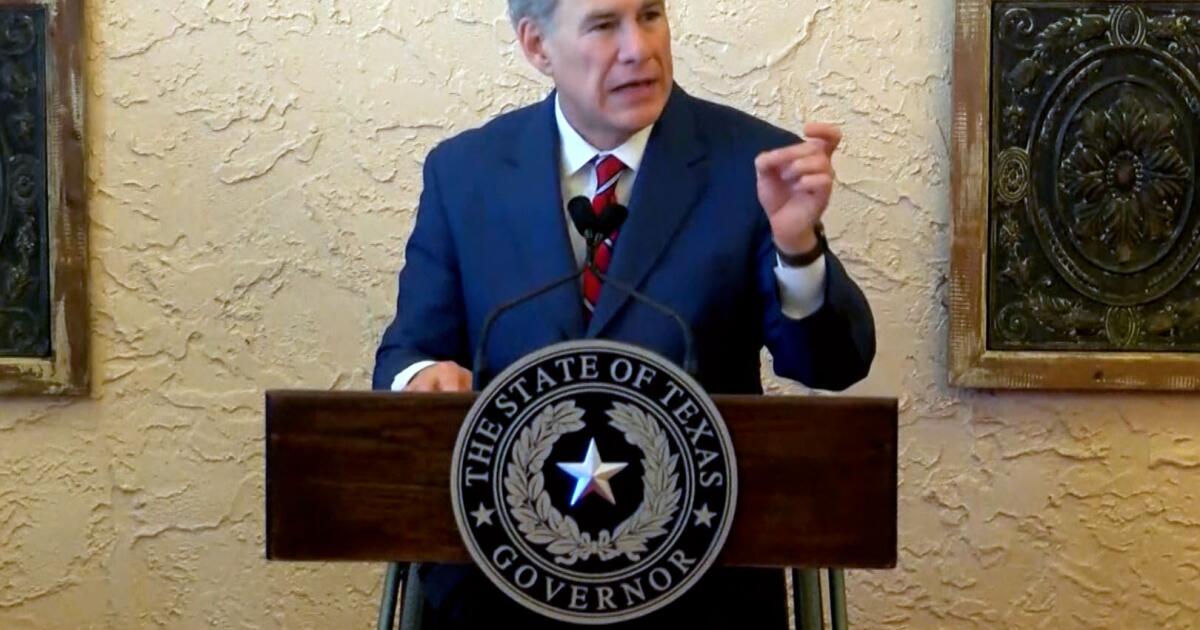

Gov. Greg Abbott agreed and by the end of August had signed into law a map with redrawn areas in and around Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth and San Antonio.

But last week, federal judges ruled in a 2-1 decision. blocked a new card from coming into force, ruling that it was unconstitutional.

“The public perception of this case is that it is about politics,” he said. wrote U.S. District Judge Jeffrey W. Brown at the beginning of the 160-page opinion. “Certainly politics played a role,” but “substantial evidence shows that Texas rigged the 2025 map on racial grounds.”

He said the most compelling evidence was obtained Mother DillonTrump Administration's Chief Civil Rights Lawyer at the Justice Department. On July 7, she sent Abbott a letter threatening legal action if the state did not eliminate four “coalition districts.”

This term, unfamiliar to many, referred to areas where no one racial or ethnic group had a majority. In one of the Houston counties targeted, 45% of eligible voters were black and 25% were Hispanic. In the neighboring county, 38% of voters were black and 30% were Hispanic.

She said the Trump administration views the actions as “unconstitutional racial gerrymandering,” citing a recent decision by the conservative 5th Circuit Court.

The Texas governor then cited these “constitutional concerns raised by the U.S. Department of Justice” when he called for a special session of the Legislature to redraw the state's map.

Voting rights advocates saw a violation.

“They said their goal was to get rid of coalition districts. And to do that, they had to create new districts along racial lines,” said Chad Dunn, a Texas lawyer and legal director of the Voting Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Brown, a Trump appointee from Galveston, wrote that Dillon was “clearly wrong” to believe those coalition districts were unconstitutional and said the state was wrong to rely on her advice as the basis for redrawing its electoral map.

He was joined by a second district judge in halting the new map and requiring the state to use the 2021 map drawn by the same Texas Republicans.

The third judge on the panel was Jerry Smith, a Reagan appointee on the 5th Circuit, and he issued a blistering 104-page dissent. Much of the report was devoted to attacks on Brown and liberals such as 95-year-old investor and philanthropist George Soros and California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“In my 37 years as a federal judge, I have served on hundreds of three-judge panels. This is the most egregious display of judicial activism I have ever witnessed,” Smith wrote. “In Judge Brown's opinion, the big winners are George Soros and Gavin Newsom. The obvious losers are the people of Texas.”

“The obvious reason for redistricting in 2025 is, of course, partisan gain,” Smith wrote, adding that “Judge Brown makes a grave error in concluding that the Texas Legislature is more partisan than political.”

Most federal cases are heard by a district judge and can be appealed first to the U.S. Court of Appeals and then to the Supreme Court.

Cases related to elections are different. A panel of three judges weighs the facts and makes a decision, which then goes directly to the Supreme Court for confirmation or overturning.

Friday Night Texas Advocates filed an emergency appeal and asked the judges to put Brown's decision on hold.

The first paragraph of their 40-page appeal noted that Texas is not alone in seeking political advantage by redrawing its electoral maps.

“California is working to add more Democratic seats to its congressional delegation to offset Texas' new districts, even though Democrats already control 43 of California's 52 congressional seats,” they said.

They argued that “last-minute disruptions to state election procedures—and the resulting confusion for candidates and voters—demonstrate” the need to block the lower court's decision.

Election law experts question this claim. “This is a problem that Texas created,” said Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

At Trump's direction, the state opted for an expedited mid-decade redistricting process.

On Monday, Dunn, a Texas voting rights lawyer, responded to the state's appeal and told the justices they should reject it.

“We're more than a year away from the election. No one is going to be embarrassed by using the map that has determined Texas congressional elections for the last four years,” he said.

“The governor of Texas called a special session to break up districts because of their racial makeup,” he said, and the justices heard clear and detailed evidence that lawmakers did just that.

However, in recent election disputes, court conservatives have often invoked the Purcell principle to exempt states from new court decisions that were too close to an election.

Authorizing the delay would allow Texas to use its new GOP-friendly map in the 2026 elections.

The justices could then hear arguments on the legal issues early next year.