As China's cities become taller, bigger and more modern, they face a major challenge: the ground beneath them is sinking. 2024 Study1 found that almost half of the land beneath the country's major cities is subsiding at a “moderate” rate, more than 3 millimeters per year, while 16% is experiencing “rapid” subsidence, or more than 10 millimeters per year.

Many of these cities, such as Tianjin, Fuzhou and Ningbo, are located by the sea. The issue of land subsidence is so pressing that a study predicts that one in 10 residents of the country's coastal cities will live below sea level by 2120 if current trends continue.

The consequences are already showing. In 2023, nearly 4,000 people in Tianjin, a port city of more than 13 million people, had to be evacuated from high-rise apartment buildings after the streets outside suddenly split. According to the city government, scientists sent to investigate the site believe the problem was caused by a “geological cavity” about 1,300 meters underground. They pointed to the drilling of a geothermal well as a possible trigger that could have caused the loss of groundwater and soil, leading to the collapse of the ground.

Nature Index 2025 Science cities

China's plight provides insight into the global crisis. Eight of the world's ten largest cities are located on the coast, including Shanghai, New York, Mumbai in India and Lagos in Nigeria, and all are experiencing a period of subsidence. The megacities that are rapidly expanding along the coasts of Asia are among the fastest sinking cities on the planet, according to a 2022 study.2.

The highest rates of subsidence were recorded in Tianjin, Vietnam's Ho Chi Minh City and Bangladesh's Chittagong; Some parts of these cities were found to be subsiding at a maximum rate of more than 50 millimeters per year. Subsidence is also widespread in North America. An analysis of 28 major U.S. cities was published this year, including coastal cities such as Houston and New York.3 It is estimated that at least one-fifth of all mapped urban areas are flooded, affecting about 34 million people.

Subsidence is not a problem that any one country can fight alone. Some Chinese cities, such as Shanghai and Guangzhou, have modeled initiatives based on what has worked in, for example, the Netherlands, one of the lowest-lying countries in the world. Local authorities encourage residents and institutions to collect and reuse rainwaterfor example, by setting 'green roofscovered with vegetation to retain rainwater and build community gardens to absorb or slow runoff.

China is also transferring its knowledge to other developing countries. In 2023, Shenzhen shared its experience of evacuating people from partially collapsed buildings with politicians from Tripoli in Lebanon as part of a joint effort organized by the United Nations Development Program to help the city better respond to natural disasters.

Chinese researchers are increasingly sharing data, writing papers and participating in workshops with international colleagues on subsidence, said Liu Jianxin, a geophysicist at Central South University in Changsha, China. And like Liu, many of them are based in inland cities that are also facing stagnation. “Combating subsidence is a global challenge,” says Liu.

Coastal problems

Coastal cities are particularly susceptible to flooding due to their natural conditions. First, they are often built in river deltas or coastal plains, where sediments become compacted over time, causing subsidence, says Ding Xiaoli, a surveyor at Hong Kong Polytechnic University who measures and monitors the shape and size of the Earth. Some coastal cities, such as Tokyo, are also located in earthquake-prone areas where tectonic activity can contribute to subsidence.

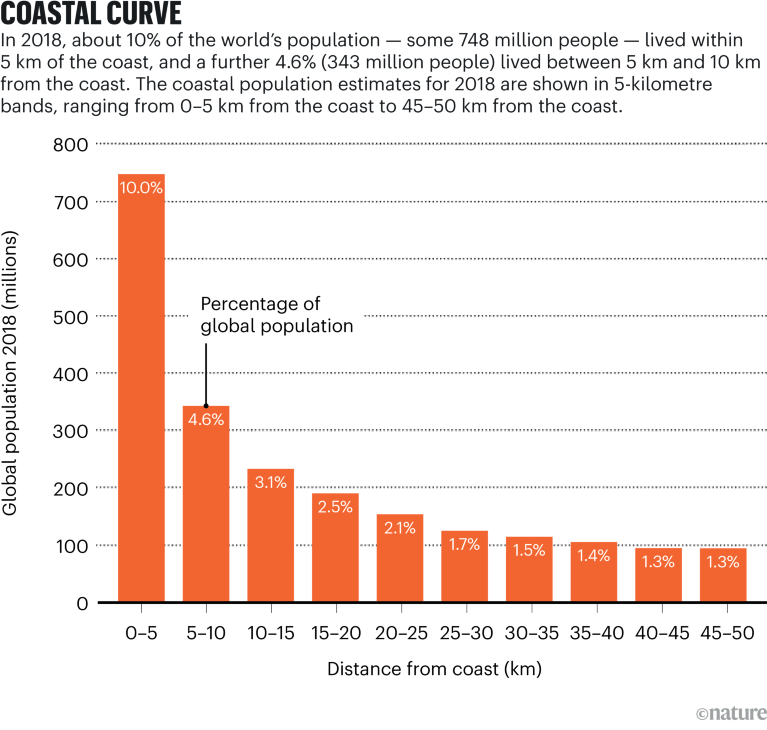

But the very growth of coastal cities—nearly a third of the world's population in 2018, or more than 2 billion people, lived within 50 kilometers of the coast—is also significantly exacerbating the problem.

Source: Cosby, AG. and other sciences. Representative. 1422489 (2024)

In China, the main cause of human-related subsidence is overextraction of groundwater as cities expand, says Zhang Yonghong, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Geodesy and Cartography in Beijing. This practice reduces groundwater levels, causing compaction of the surrounding soil and subsidence of the land. “Construction of infrastructure such as the subway could also lead to the collapse of some parts of the city,” Zhang says.

Disruption of natural groundwater recharge by paved urban surfaces could make the situation worse, says Yu Congjian, a landscape architect at Peking University in Beijing. “Land subsidence is one of the most profound manifestations of environmental mismanagement in urban regions,” he says.

Cities also become heavier as they grow, says Zhao Qing, a surveyor at East China Normal University in Shanghai. Her team's ongoing research suggests that increasing building weight is one of three factors (along with falling groundwater levels and soil character) that are causing subsidence in Shanghai and other cities in the Yangtze River Delta region.

None of the above is unique to China, and some of these issues, such as groundwater extraction and building weight, often affect inland cities as well. But on the coast, these factors lead to land subsidence in areas that are also face accelerated sea level rise due to climate change.

Over the past three decades, the rate of sea level rise has more than doubled.4increasing from approximately 2.1 millimeters per year in 1993 to approximately 4.5 millimeters per year in 2023. By the end of this century, global average sea level is projected to be 0.55 meters higher than the 1995–2014 average, even if the world limits global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, as called for in the Paris Agreement.

2022 Study5 A study of 99 coastal cities around the world found that in most of them, parts of the land were subsiding faster than sea levels were rising. On current decline trajectories, they will experience flooding much earlier than the timing predicted by sea level models, the authors say.

One of the cities hit by this double blow is Jakarta, the current capital of Indonesia, an archipelago country on front line in the fight against sea level rise. More than 40% of the city is already below sea level – where the risks of flooding, storm surge, infrastructure damage, and economic and human losses are particularly high – and by mid-century 95% of its coastal areas may be flooded. The grim outlook was a major factor behind Indonesia's decision to move its capital to another island by 2028.

Since 2014, Indonesia has been building a 32-kilometer “Giant Sea Wall” in an attempt to protect Jakarta from flooding, a project expected to cost US$50 billion. But sea walls have shallow foundations, so they follow the movement of land, says Pietro Teatini, a hydrologist at the University of Padua in Italy and chairman of UNESCO's International Land Subsidence Initiative (LaSII), a working group that aims to spread knowledge about land subsidence around the world and help developing countries deal with the problem more effectively. “If the ground settles, the wall will settle too,” he says.

Successful measures

Shanghai, the first city in China to identify subsidence, is also facing the compounding effects of sinking land and rising sea levels. From 1921 to 1965 it sank by 1.69 meters as a result of excessive pumping of groundwater. According to Ye Shujun, a hydrogeologist at Nanjing University in China, the city government has taken a number of measures to address the problem over the past 60 years, mainly by limiting groundwater use and replenishing groundwater reserves with water from the Yangtze River. These methods have reduced Shanghai's rate of subsidence to 6 millimeters per year, said Ye, who shared the city's experiences in a webinar organized by LaSII in early 2025.

According to Teatini, a lot of work has been done in China to address the subsidence problem from a scientific and technical perspective. He said “one of the most important” steps to combat subsidence is artificial groundwater recharge, which has proven effective in Shanghai. But he warns that the method is expensive, so it may be difficult to implement in poorer countries.

Teatini points to the advanced equipment that Chinese cities use, such as extensometers that measure how materials change under load. Researchers drill down, sometimes nearly 1,000 meters, to place devices at the bottom of Earth's aquifers, known as aquifer systems, and monitor which layers are compacting. “In Italy we have three or four [extensometers] spread throughout the country. There are about 50 in Shanghai,” says Teatini, who regularly works with Chinese researchers.

Some of Teatini's long-time collaborators come from the Capital Normal University in Beijing, which has established an official partnership with the University of Padua. They have collaborated on a number of studies, ranging from assessing the causes of Beijing's fall to developing models to predict the problem.

China's efforts to reduce land subsidence have been “very, very effective,” Teatini said. One of his achievements is related to Water transfer project from south to northa colossal infrastructure project launched by the government to redirect water from the south of the country to the water-stressed north. Although the main goal of the project is to balance water supplies, it has played a critical role in mitigating long-term subsidence of the North China Plain by reducing groundwater extraction. Before the project came online in 2014, Beijing, in the country's arid north, relied heavily on groundwater and suffered severe subsidence of up to 159 millimeters a year as a result.