Pallab GhoshScience correspondent

Getty

GettyFor the first time, the Government has detailed how it intends to deliver on its manifesto pledge to work towards phasing out animal testing.

The new plans include replacing animal testing with some large safety trials by the end of this year and reducing the use of dogs and primates in human drug trials by at least 35% by 2030.

The Labor Party said in its manifesto that it would “work with scientists, industry and civil society to work towards phasing out animal testing”.

Science Minister Lord Vallance told BBC News he could imagine a day when the use of animals in science was almost completely phased out, but admitted it would take time.

Animal experimentation in the UK peaked at 4.14 million in 2015, mainly due to a significant increase in genetic modification experiments – mainly on mice and fish.

By 2020, this number had plummeted to 2.88 million as alternative methods were developed. But the decline has since stopped.

Lord Vallance told BBC News he wants to resume the rapid decline by replacing animal testing with experiments on animal tissue grown from stem cells, artificial intelligence and computer modeling.

Asked by BBC News if he could imagine a world in which there was “almost zero” animal testing, he said: “I think it's possible, but it's not possible anytime soon, the idea that we can stop using animals in the foreseeable future I don't think exists.

“Can we get closer to this? I think we can. Can we move faster than we are now? I think we can. Should we? We absolutely should.”

“This is the moment to really recognize this and take alternative approaches,” he said.

Scientists will stop using animals for some major safety tests by the end of 2025 and switch to newer laboratory methods that use human cells instead, according to detailed new government plans.

As a former chief scientific adviser to the government and a former head of research at a major pharmaceutical company, he knows that many scientists believe that achieving “near-zero” animal testing will be extremely difficult, even in the long term. This includes those who are strong proponents of animal-free methods.

“I firmly believe this is not possible for safety reasons,” said Professor Frances Balkwill of the Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London.

Professor Balkwill is working to find ways to stop the recurrence of ovarian cancer using mice as well as non-animal methods, of which she is a big fan.

“These non-animal methods will never replace the complexity that we can see when we have a tumor growing throughout an entire body, such as in a mouse,” she said.

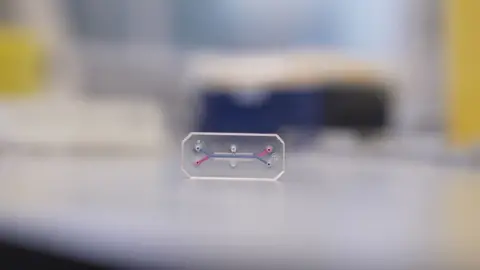

Kevin Church/BBC News

Kevin Church/BBC NewsOne of the world's leading centers for developing alternatives to animal testing is the Center for Predictive Modeling (CPM) at Queen Mary University of London.

Researchers are developing unusual-sounding organ-on-a-chip technology, conjuring up disturbing images of pulsating brains and beating hearts sitting on electronic circuits.

However, the reality is much less science fiction.

Some small pieces of glassware containing tiny samples of human cells from various organs of the body, such as the liver or brain, are connected to electrodes that send information to a computer.

What's amazing, according to CPM co-director Professor Hazel Screen, is that cells from different parts of the body can connect together, mimicking different organs working together.

“Theoretically, any organ can be built on a chip. Then I can use it to test a new drug,” she said.

“And because we’re taking human cells, we’ll be able to do higher quality scientific research.”

The safety tests, which the government says will no longer use animals by the end of this year, involve the practice of giving rabbits a small dose of a new drug – a so-called pyrogenicity test. It says this will be replaced by a test using human immune cells in a dish.

The government says all tests that used animals to screen for dangerous microbes in medicine will also be done using cell and gene technologies.

Between 2026 and 2035, the government plans to accelerate the use of non-animal technologies, including organ-on-a-chip devices and artificial intelligence.

The proposals divide animal tests into two main groups: those that can be immediately replaced because safe and effective alternatives already exist and simply require updated laws or guidelines; and others where alternatives exist but still need development to prove they are reliable enough for widespread use.

To speed up the latter, the government plans to create a Center for Validation of Alternative Methods.

Ministers are also promising an unspecified increase in funding and investment to develop new alternatives, including £30 million for a research center and additional grants to support innovative methods and training.

The RSPCA cautiously welcomed the plan, calling it a “significant step forward”, but called on the government to follow through.

Some scientists working with animal experiments, such as Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, are deeply concerned about what they believe could be a premature push towards alternatives and its potential negative consequences for science and medicine.

“What about the brain and behavior? How can you study behavior in a Petri dish? You just can't,” he says.

“How can forcing this strategy help in complex areas of biology where no current non-animal model comes close to real biology?”