In Martin County, the government shutdown and attacks on food stamps have exposed Donald Trump's empty promises. To many, this makes him just another politician.

On an April morning in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson touched down in Martin County, Kentucky, crossing from Marine One into the bustle of a rural county where 60 percent of residents lived in poverty. With reporters and photographers from Time And Life in tow, Johnson found himself on the porch of the cabin of Tom Fletcher, a father of eight who had been unemployed for two years. After hearing the Fletchers' story, Johnson stepped off the porch, turned to the press and declared: “I have called for a national war on poverty. Our goal: total victory.”

Johnson was referring to a statement he made earlier that year before a joint session of Congress during his State of the Union address when he declared a “War on Poverty.” Martin County, he made clear, will be on the front lines.

By August, Johnson had signed the Food Stamp Act, which—along with Medicaid, Medicare and Head Start—federalized the tools he promised to use during this tour in places like Martin County.

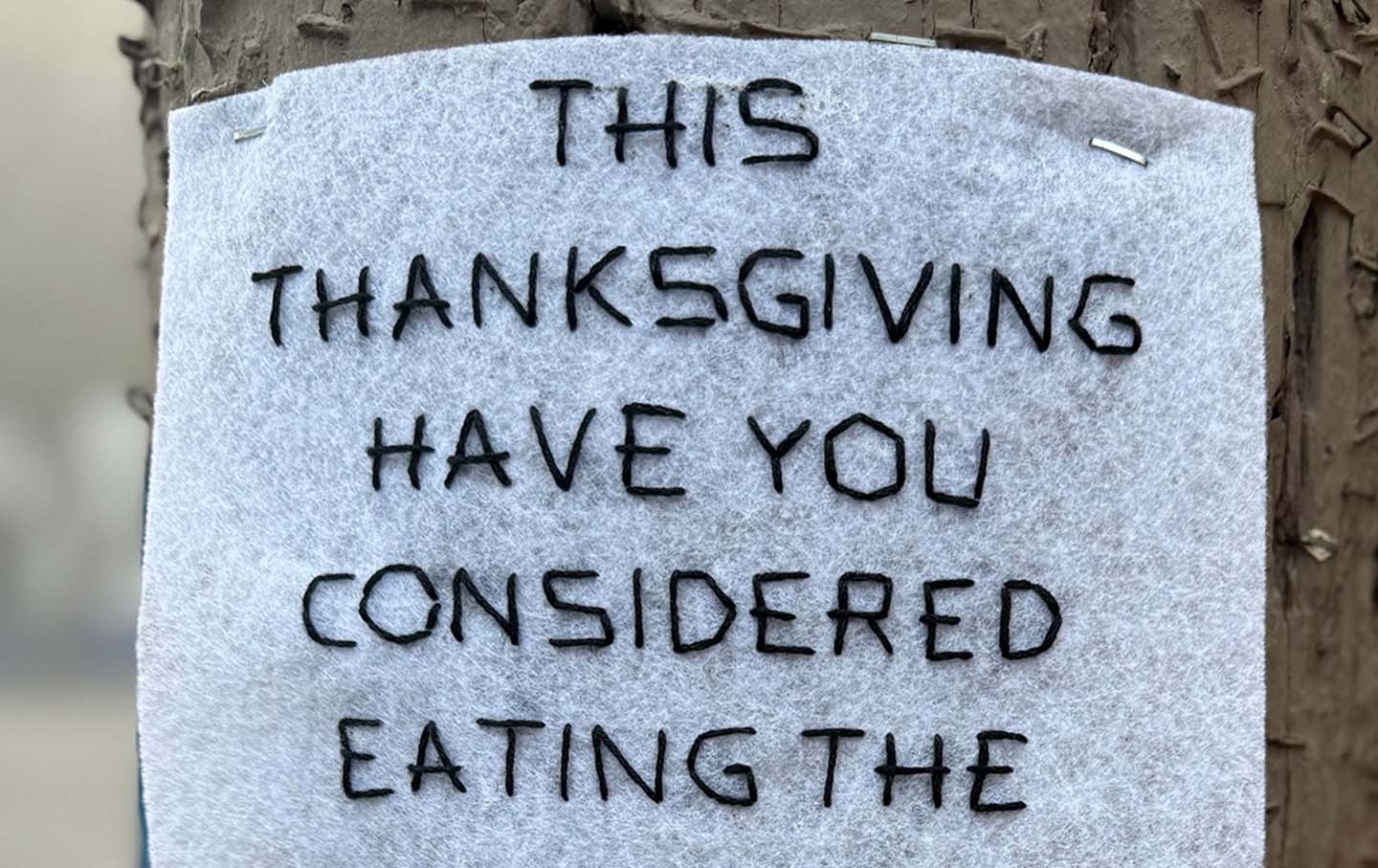

This month, the longest government shutdown in U.S. history created the deepest disruptions to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program since Johnson made it permanent. In Martin County, families are preparing for Thanksgiving as approximately 23 percent of residents, or about 1,300 families, rely on SNAP to put food on the table. And although the lockdown has ended, for many voters a return to the status quo is not enough.

In 2024, 91 percent of the county's voters supported Donald Trump. However, how New York Times As recently reported, it was the Trump administration that pressured states like Kentucky to scale back efforts to provide full food stamps during the shutdown. “SNAP benefits were paid out in full for October, so recipients would only see the impact on their household budgets starting in November,” said Harris Eppsteiner, associate director of economic analysis at the Yale Budget Lab, a nonpartisan policy research center. The effect “depends on what state you're in,” he said. “Some states issued full SNAP benefits for November, while about two-thirds issued partial or zero benefits.”

Kentucky was among the two-thirds, according to the Kentucky Economic Policy Center, whose director Jason Bailey said SNAP recipients in Kentucky received partial benefits on Nov. 6.

In response to the government shutdown, Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear committed $5 million to support food banks, an amount that Bailey called a “temporary measure” given that monthly SNAP appropriations in Kentucky are about $105 million.

“SNAP is a program designed to fight hunger,” Bailey said. “Many working people also qualify for the program because their wages are too low.” What Washington calls “work requirements,” he argues, are more accurately “paperwork requirements” that deny people benefits “because of systems that are deliberately made difficult to comply with, not because of people's inability to work.” The closure was just a preview of what's to come, he said.

Trump's “one big, beautiful bill” would also threaten SNAP benefits for 114,000 people, or about one-fifth of recipients, in Kentucky, where work requirements would now expand to about 50,000 people ages 54 to 65, as well as caregivers of children over 14, starting in early 2026. The bill also expanded work requirements for military veterans and people experiencing homelessness — effectively pushing many out of a program they rely on to avoid going hungry. “This is especially problematic,” Bailey said, “because we have the second-highest rate of food insecurity in the United States for adults over 50.”

Starting next year, Bailey told me, the Kentucky Assembly will have to finance the deficit caused by Trump's bill—up to $188 million a year.

In Martin County, where there is no major grocer, SNAP dollars circulate through six small stores: two Dollar Generals, two Family Dollars, Save A Lot and Warfield Market, a store once affiliated with IGA and now the only independently owned grocery store in the county. “We had low sales the first couple weeks of November,” said Ron Jones, assistant manager. “Everyone came together to try to help. I live in an apartment building and the office prepares meals for all the children living in the building.” During the final days of the closure, Jones told me, “the office made 30 pounds of bean soup and cornbread.”

“Honestly,” he said, “I see people coming in and out of the store every day and they're suffering from it. They're really worried about doing it because they have kids to feed.” The store's regular customers disappeared for almost two weeks. “We typically make $15,000 a day, and during the shutdown our sales dropped to $7,000 a day.”

Thomas Howell, a 25-year-old line worker at a fast food restaurant in Martin County, works five days a week for $8 an hour. “It sucks, but right now I don’t have my own car and that’s pretty much the only job opportunity I have,” he said. “If I make $170 a week, I consider that a really good week. And I get $110 a month in food stamps. That's pretty much all the food I have unless someone else buys it for me.”

Without food stamps, he had to find other ways to afford to eat. “There’s a discount candy store near me that sells food items that are about to expire for a quarter apiece.” During the government shutdown, Howell ate discounted candy bars and beef jerky that couldn't be sold at grocers. “I don’t like going to food banks unless I’m really going to starve because I know there are people who if they don’t have food, they’re going to starve.”

Howell liked Trump in 2016, when he was too young to vote; and voted for president in 2020 and 2024. But he told me that his support ended this year. During the shutdown, “he seemed unwilling to cooperate with any amount of funding when it came to food stamps and simply shifted the blame to the Democrats.” He believes both sides are to blame, but stressed that only “poor people” suffered. His grandmother, who taught public school her entire life and now survives on less than $900 a month, including food stamps, must rely on food banks.

“I’m really disappointed in the minimal effort Trump is making for us poor people,” he told me. “I think most of this country voted for Trump based on empty promises,” he said, “hoping that he would give us a better future, but instead it seems like everything is going in the complete opposite direction. I pray to God I'm wrong.”

Trump's net approval rating in Kentucky is now just 0.2 percent, according to recent projections. “Once the honeymoon ends, presidents tend to quickly fall out of favor,” writes Economist. “But no recent president has fallen as low or as fast as Donald Trump.” And while a majority of Martin County voters supported President Trump in 2024, the majority of the county's registered voters simply didn't vote. In the last presidential election, the county had the second-highest voter turnout of any Kentucky county, at just 49 percent.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

“I have not and will not vote for him because I know he will not help the people of Martin County,” said another voter, who spoke on condition of anonymity because she fears retaliation in her workplace. Although she is a Republican, she believes that “he absolutely failed to keep his campaign promises.”

But disillusionment with Trump or other Republicans of the past doesn't seem to have translated directly into enthusiasm for Democrats either. The last Democrat Kentucky endorsed for president was Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996. “The last time I voted was when Bush was running,” said Dina Lynn Howell (who is not directly related to Thomas Howell), a 58-year-old Martin County resident. “I don’t believe or trust anyone who is running for president,” she said.

What is happening in Kentucky is not so much a political realignment as a relinquishment of power. While the presidential election was won exclusively by Republicans, Kentucky has elected Democratic governors, including current Governor Beshear, whom Thomas Howell voted for. “A lot of people here think the word ‘Democrat’ is a bad word,” he told me, “but it’s all about the individual.” But no matter who Martin County endorsed for president or what progress has been made in the fight against poverty, life doesn't seem to be getting any easier, voters say. There is no feeling that anyone is listening. “Nobody wants to talk to us,” Thomas Howell told me. “They just like to point fingers at downtrodden villagers.”

More from Nation

The Democrat has a real shot at winning a deep-red congressional seat. In an exclusive interview, she explains why her proposal will shake up politics in 2025 (and maybe 2026).

The rise, fall and rise again of the journalist looks like a performance in a tabloid drama. But in reality these are reports of ring road access taken to their natural limits.