Justin RowlattClimate editor And

Matt McGrathEnvironment Correspondent

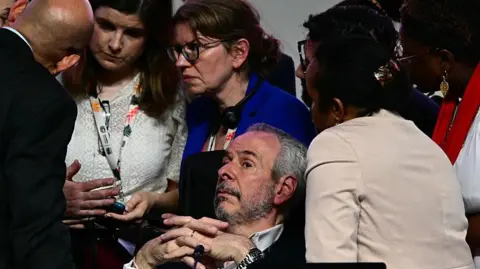

Getty

GettyIn three decades of these meetings aimed at building a global consensus on how to prevent and cope with global warming, it will rank among the most divisive.

Many countries were furious when COP30 in Belem, Brazil, ended on Saturday without mention of fossil fuels that have warmed the atmosphere. Other countries—especially those that benefited most from continued production—felt vindicated.

The summit was a reality check on how frayed the global consensus is on how to deal with climate change.

Here are five key takeaways from what some call the “CS of Truth.”

Brazil is not their finest hour

The most important thing to come out of COP30 is that the climate ship is still afloat.

But many participants are unhappy that they didn't get anything close to what they wanted.

And despite great warmth towards Brazil and President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, there is disappointment over the way they handled the meeting.

From the very beginning, there seemed to be a gap between what President Lula wanted to achieve at this meeting and what the President of the COP, President André Corrêa do Lago, thought was possible.

So Lula spoke about road maps for a transition away from fossil fuels to a handful of world leaders who came to Belém ahead of the official start of the COP.

The idea was taken up by a number of countries, including the UK, and within days a campaign began to formally include the roadmap in the negotiations.

I wasn't thrilled with Lago. His north star was consensus. He knew that putting fossil fuels on the agenda would destroy this situation.

Although the original text of the agreement contained some vague references to things that looked like a road map, after a few days they disappeared and never returned.

Colombia, the European Union and about 80 countries have been scrambling to find language that would signal a stronger move away from coal, oil and gas.

To find consensus, Do Lago convened a mutiran, a kind of Brazilian panel discussion.

This made the situation even worse.

Arab negotiators refused to join those who wanted to divest from fossil energy.

The largest producers did not pay enough attention to the EU.

“We are making energy policy in our capital, not yours,” a Saudi delegate told them at a closed meeting, according to one observer.

Oh!

Nothing could bridge the gap – and negotiations were on the verge of failure.

Brazil came up with the life-saving idea of creating roadmaps for deforestation and fossil fuel use that would exist outside the COP.

They were greeted with warm applause in the plenary chambers, but their legal status is unclear.

Tom Ingham/BBC

Tom Ingham/BBCI had a bad cop

This is the richest group of countries still in Paris Agreement but this COP was not the finest hour of the European Union.

While they bragged about the need for a fossil fuel roadmap, they painted themselves into a corner on another aspect of the agreement that they ultimately couldn't get out of.

The idea of tripling money for adaptation to climate change was in the original text and remained until the final version.

The wording was vague, so the EU did not object, but, crucially, the word “triple” remained in the text.

So when the EU tried to pressure developing countries to support the idea of a fossil fuel road map, they had nothing to sweeten the deal – since the concept of tripling was already in place.

“Overall, we see the European Union being backed into a corner,” said Li Shuo of the Asia Society, a longtime observer of climate policy.

“This partly reflects real-world power shifts, the growing power of the BASIC and BRIC countries, and the decline of the European Union.”

The EU was angry, but on top of moving the tripling of funding from 2030 to 2035, they had to agree to this agreement and they achieved very little on the fossil fuel front.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe future of the Constitutional Court is in doubt

The most persistent question asked here at COP30 for two weeks concerned the future of the “process” itself.

Two frequently heard positions:

How stupid is it to fly thousands of people halfway around the world to sit in giant air-conditioned tents arguing about commas and the interpretation of confusing words?

How ironic is it that key discussions here about the very future of how we power our world are taking place at 3am among sleep-deprived delegates who haven't been home for weeks?

The idea of COP served the world well, eventually producing the Paris climate agreement – but that was a decade ago, and many participants believe it no longer has a clear and powerful purpose.

“We can't completely abandon this,” Harjit Singh, an activist with the Fossil Fuel Treaty Initiative, told BBC News.

“But it requires modernization. We will need processes outside of this system to help complement what we have done so far.”

Energy costs and pressing questions about how countries achieve net-zero emissions have never been more important, yet the idea of COP seems very far removed from the daily lives of billions of people.

This is a consensus-building process from another era. We are no longer in that world.

Brazil has recognized some of these problems and has tried to turn him into an “implementation policeman” and put more emphasis on the “energy agenda.” But no one really knows what these ideas actually meant.

CoP leaders are reading the room – they are trying to find a new approach that is needed, otherwise this conference will lose all relevance.

Trade comes in from the cold

For the first time, global trade became a key issue in these negotiations. According to veteran COP watcher Alden Meyer of the climate think tank E3G, there were “planned” attempts to raise the issue in every negotiating room.

“What does this have to do with climate change?” you're probably thinking.

The answer is that the European Union is planning to introduce a border tax on some high-carbon products such as steel, fertilizers, cement and aluminum, and many of its trading partners – especially China, India and Saudi Arabia – are unhappy about it.

They say it is unfair for a large trading bloc to impose what they call a unilateral (that's the technical term for “unilateral”) measure like this because it would make the goods they sell to Europe more expensive and therefore less competitive.

Europeans say this is wrong because the measure is not aimed at suppressing trade but at cutting planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions and tackling climate change. They already charge their producers of these products a fee for the emissions they create, and say the border tax is a way to protect them from less environmentally friendly but cheaper imports from abroad.

If you don't want to pay our border tax, they say, just charge your polluting industries – collect the money yourself.

Economists like this idea because the more expensive it is to pollute, the more likely we are to all switch to clean energy alternatives. Although, of course, this also means that we will pay more for any products we buy that contain polluting materials.

This issue was resolved here in Brazil with the classic COP compromise of deferring discussions to future negotiations. The final agreement launched an ongoing dialogue on trade for future UN climate negotiations involving governments as well as other participants such as the World Trade Organization.

Tom Ingham/BBC

Tom Ingham/BBCTrump wins if he stays away – China wins if he stays silent

The world's two largest carbon emitters, China and the US, had similar influences on this COP, but did so in different ways.

US President Donald Trump stood aside, but his stance has emboldened his allies here.

Russia, usually a relatively quiet participant, has been at the forefront of blocking efforts to implement the road maps. And while Saudi Arabia and other major oil producers have been predictably hostile to curbing fossil fuel production, China has remained silent and focused on deal-making.

And eventually, experts say, the business China is doing will surpass the United States and its efforts to sell fossil fuels.

“China has maintained a low-key policy stance,” says Li Shuo of the Asia Society.

“And they focused on making money in the real world.”

“Solar is the cheapest source of energy, and the long-term direction is very clear: China dominates this sector, and that puts the US in a very difficult position.”