Archaeologists have discovered Africa's oldest known cremation pyre at the foot of Mount Hora in Malawi. According to paper Radiocarbon dating results published in the journal Science Advances date the site to about 9,500 years ago, prompting a rethinking of group labor and rituals in such ancient hunter-gatherer societies.

Many cultures practiced some form of cremation. Exists Viking cremation site known as Kalvestene on a small island Hjarno in Denmark, for example. And again in 2023 we reported at an unusual Roman burial ground, where the cremated remains were not moved to a separate final resting place, but remained in place, covered with brick tiles and a layer of lime and surrounded by several dozen bent and twisted nails – perhaps attempt so that the deceased does not rise from the grave and persecute the living.)

But this practice was extremely rare among hunter-gatherer societies because building a fire is labor-intensive and requires large amounts of community resources. There is very little evidence of cremation preceding middle Holocene (between 5000 and 7000 years ago). According to the authors of this latest paper, the earliest known concentration of burnt human remains was found at Lake Mungo in Australia and dates back to 40,000 years ago, but there is no evidence of a fire, making specific details difficult to determine.

The oldest fire site discovered to date is the Xaasa'a Na site in Alaska, dating back to approximately 11,500 years ago and containing the remains of a three-year-old child. There is evidence of burnt human remains in Egypt dating back to approximately 7,500 years ago, but the earliest confirmed cremations in the region date back to just 3,300 years ago.

This is why the discovery of an intact hunter-gatherer cremation pyre containing the remains of an adult woman at the Hora 1 site is so significant. Situated under a canopy at the foot of a granite hill, Chora 1 was first excavated in the 1950s. Archaeologists have determined that this was a burial ground between 8,000 and 16,000 years ago, containing several intact (uncremated) bodies. The fire is unique: the ash layer contains 170 fragments of bones, mainly arms and legs. This is the only example of cremation at this site.

Bed of Ashes

The events of the 9,500-year-old bonfire have been reconstructed.

Patrick Fahey

Restoration of cremated remains.

Grace Veatch

The sediment walls show streaky layers of fire ash.

Flora Schilt

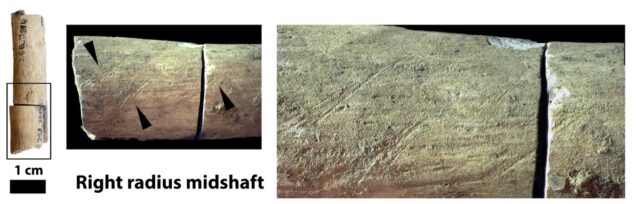

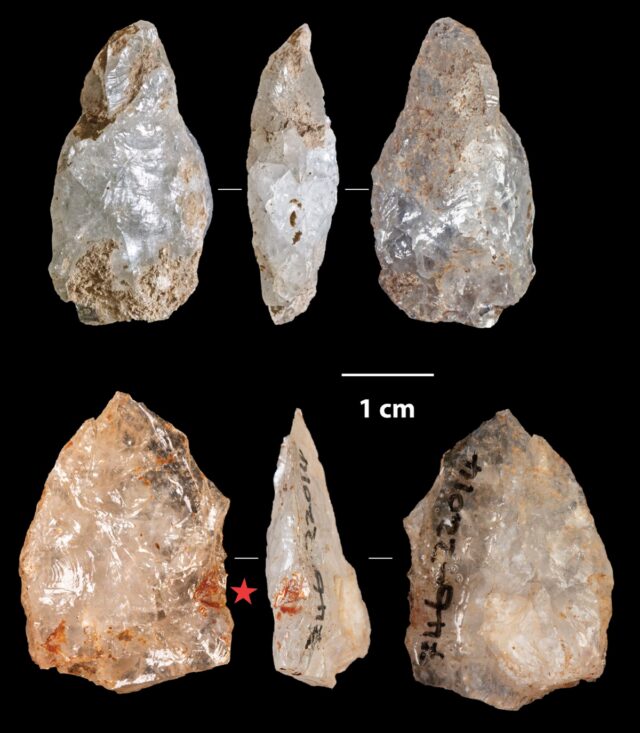

An examination of the remains found at the site of the fire revealed that they belonged to an adult female between the ages of 18 and 60, who was likely cremated several days after her death. The team also found distinctive cuts on several of the bones, suggesting the bones had been skinned before cremation. Given the lack of teeth and skull in the pyre, it appears that whoever cremated the woman also removed the head. The body was probably positioned with the arms and legs bent, depending on the placement of the limbs.