For most summer Sundays, Michele Facchini wasn't near the sweltering hot, low and flat fields northwest of Ravenna, Italy, with a metal detector.

However, it was here that he unexpectedly met Hector MacDonald from Cape Breton, a soldier killed in action in 1944.

Facchini, 49, a World War II researcher and educator, usually spends summer weekends at home, reading the diaries of Canadian soldiers and tracking maps of the battle.

On July 6, he took advantage of the cool weather and headed to the outskirts of the city of Russi, near the Lamone River.

There, in December 1944, about 10,000 Canadian troops moved out to push Nazi troops out of northern Italy. His research revealed that the platoon fought in the field, dodging bullets and bombs and dodging mines as the men advanced toward the river through cold, marshy terrain.

Facchini's metal detector was triggered by the remains of bullets and fragments of high-explosive bombs. Then the farmer whose land he was on brought him some items that were gathering dust in a small warehouse on his land.

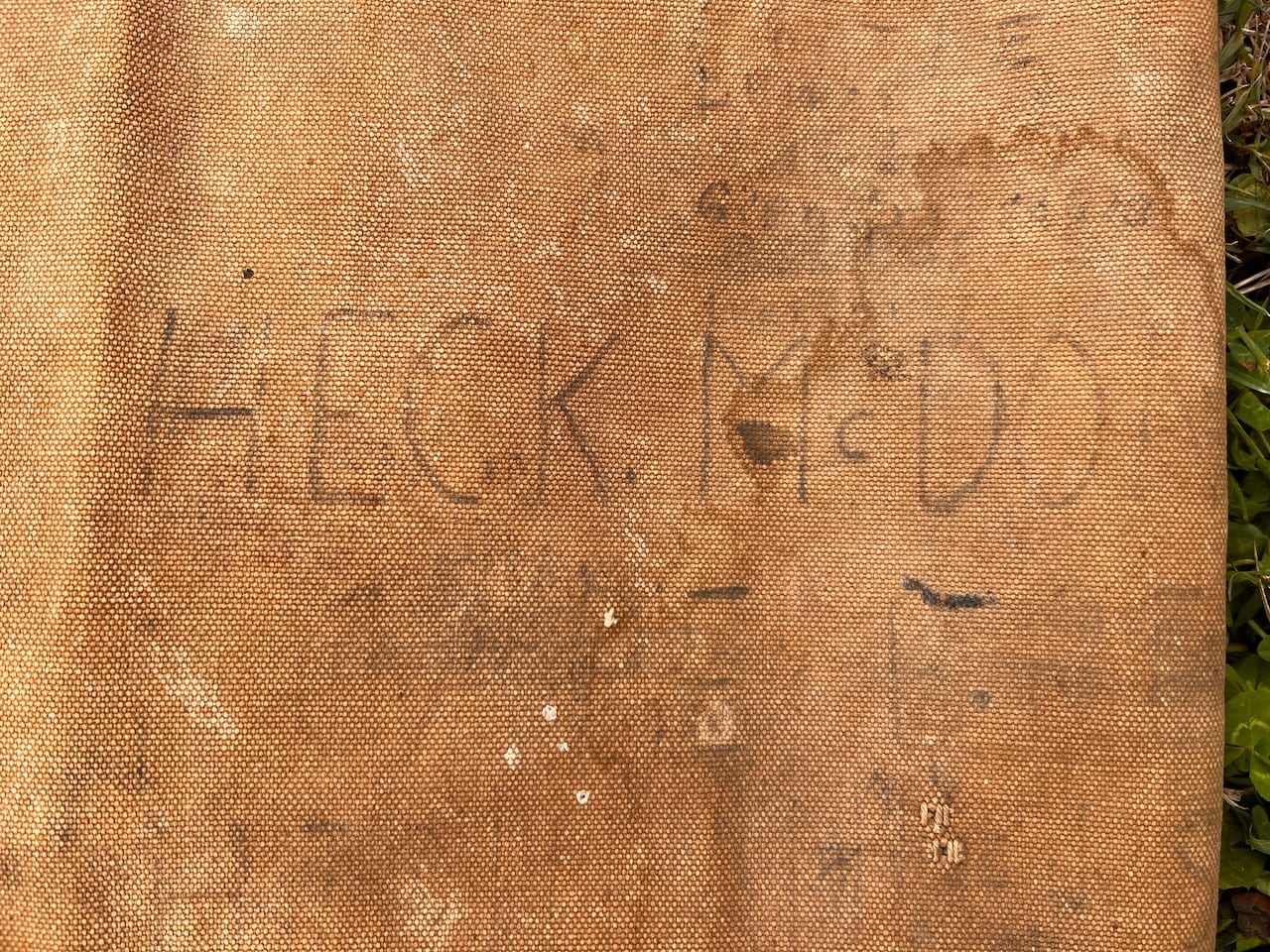

“That’s when I saw the duffel bag in which the good soldiers kept their personal belongings,” Facchini said. “It was covered in mud, but underneath I could make out letters indicating the name and numbers of the regiment.”

The chance discovery would revive a story left untouched for 81 years and reunite MacDonald with the family that never forgot him.

Not a single photograph of Hector Colin MacDonald survives, but there is a portrait in wartime documents.

He was wiry, five feet nine inches tall and weighed 137 pounds. He had brown eyes and light brown hair. His behavior is noted as “fair” and “correct.” He was the third of six children.

He was a young man who left school in New Aberdeen, Cape Breton, at age 15 to work in the Dominion Coal Company mines, like most of the men in his family, hoping to one day become a welder.

Instead, in late 1941, at the age of 25, Macdonald went to fight in World War II, like thousands of young Canadians, because, as his file noted, it was “the right thing to do.”

He joined the Northern Nova Scotia Highlanders and continued through some of the fiercest battles of the Italian Campaign.

These included the Allied invasion of Sicily, the landings at Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland, brutal street fighting at Ortona, and the persistent effort to break out at Monte Cassino.

Then came his final journey—an icy, mud-strewn advance north to the Lamone River. They were sure it would take two days, but in fact it took 12. In total, 548 Canadians died liberating Ravenna and its environs.

McDonald, a lance sergeant, marked each of his battles on his duffel bag. Some names are still readable. “Sicily. Italy. Ortona. Cassino.” Others faded.

Among the unrecorded attacks he survived was the accidental Allied bombing of McDonald's own regiment on December 3, caused by outdated intelligence about their location.

A week later, just over a month before his 29th birthday, the Cape Breton man was killed when a mine planted by retreating German troops exploded on a small bridge over the Lamone River. The date of death was recorded as December 13, 1944, but Facchini says that date likely reflects the time his body was recovered, two days after several soldiers stepped on mines on the bridge.

He was buried with other fallen soldiers in a nearby farmer's field and later buried in Ravenna's military cemetery in 1946.

When MacDonald died, he was probably still engaged to Elizabeth Wales, a Scotswoman whom he had met abroad. Before setting off on the Italian campaign, he asked permission to marry her. Among his personal belongings were a rosary, which, according to the chaplain's memoirs, she gave him.

“Her name was Elizabeth Wales and she lived in the Glasgow mining district,” said Mariangela Rondinelli, a teacher and local World War II history expert who founded Wartime Friends, a group dedicated to honoring Canadians who fought and died in Italy. “We know everything about this woman, her father's name, her address, but we haven't been able to find her family.”

Rondinelli and Facchini are part of a small network of World War II researchers who have spent years documenting the stories of mostly Canadian soldiers who fought in the region, often reuniting descendants with the communities that sheltered or helped them.

One of the group's members, Raffaella Cortese de Bosis, helped verify MacDonald's identity and then tracked down his family—no small feat with a name as common as MacDonald.

Her search took several weeks and eventually led her to his great-granddaughter Kim Pike, a Canadian Forces veteran in Kingston, Ont.

“You have to be careful when you contact possible relatives,” Cortese de Bosis said, “because sometimes the person hurt the family, had another wife, things like that. But when I contacted Kim Pike, she immediately responded, ‘Hector MacDonald was my great-uncle.’ That’s when the tears started flowing.”

“My mom and two brothers are still alive and they're waiting with bated breath to see the bag. It's very emotional,” Pike said.

On Saturday, a ceremony was held in Russia with the participation of MacDonald's relatives.

Pike was unable to attend for personal reasons, but her 23-year-old daughter Stacey Jordan traveled to Russie to take part in a local ceremony for the man the family affectionately called “Hecky”, where she was presented with a bag.

“A discovery like this in itself is extraordinary,” Jordan said, “especially since he comes from my family tree, but also comes from a family where so many people serve in the military, both parents, my grandfather and uncle. It's really close.”

She said many family members still live in Glace Bay, some just steps from Hector's home in what was then a mining company row house.

Coincidentally, another young relative, 14-year-old Cain Risold McDonald of Creston, British Columbia, had just submitted a school project on Hector when the duffle bag surfaced.

“I was very excited and disappointed at the same time because I could have included a duffel bag in the report,” he said of the discovery. “But it was really great that my report came out and a month later they found his bag.”

Facchini calls the discovery, made 81 years after Hector MacDonald's death, “absolutely one of a kind.”

“For me, it’s not about the object,” he said. “I never go to flea markets looking for paraphernalia.

“We are talking about people who suffered, persevered and sacrificed a lot. This is not just a sports bag. It belonged to a Canadian who traveled across the ocean to fight against dictatorship, Nazism and fascism. His story matters.”

MORE STORIES