Justin RowlattClimate editor And

Jessica CruzSouth American producer

BBC/Tony Jolliffe

BBC/Tony JolliffeThe Amazon rainforest could face a new wave of deforestation as efforts to lift a long-standing ban that protected it could intensify.

The ban, which prohibits the sale of soy grown on land cleared after 2008, is widely credited with curbing deforestation and is seen as a global environmental success story.

But powerful farming interests in Brazil, backed by a group of Brazilian politicians, are pushing for the restrictions to be lifted as the UN COP30 climate conference enters its second week.

Critics of the ban say it is an unfair “cartel” that allows a small group of powerful companies to dominate the Amazon soy trade.

Environmental groups have warned that lifting the ban would be a “catastrophe”, opening the way for a new wave of land grabs to plant more soybeans in the world's largest rainforest.

Scientists say continued deforestation, combined with the effects of climate change, is already pushing the Amazon toward a potential “tipping point”—the threshold beyond which the rainforest can no longer sustain itself.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBrazil is the world's largest producer of soybeans, a staple crop grown for protein and important animal feed.

Most meat consumed in the UK, including farmed chicken, beef, pork and fish, is raised using feed containing soybeans, around 10% of which is sourced from the Brazilian Amazon.

Many of the UK's major food companies, including Tesco, Sainsbury's, M&S, Aldi, Lidl, McDonald's, Greggs and KFC, are members of the coalition called British soya manifesto which accounts for around 60% of soya imported into the UK.

The group supports the ban, which is officially known as the Amazon Soy Moratorium, as they believe it helps ensure the UK's soy supply chains remain free of deforestation.

In a statement earlier this year The signatories stated: “We call on all participants in the soybean supply chain, including governments, financial institutions and agribusinesses, to strengthen their commitment to [ban] and ensure its continuation.”

Public opinion in the UK also appears to be strongly in favor of protecting the Amazon. WWF study Research earlier this year found that 70% of respondents supported government action to eliminate illegal deforestation from UK supply chains.

BBC/Tony Jolliffe

BBC/Tony JolliffeBut Brazilian opponents of the agreement last week demanded that the Supreme Court, the country's highest court, reopen the investigation the question of whether the moratorium constitutes anticompetitive behavior.

“Our state has a lot of room to grow and the soybean moratorium is hindering that growth,” Vanderlei Ataides told the BBC. He is president of the Soybean Farmers Association of the state of Pará, one of Brazil's main soybean producing regions.

“I don't understand how [the ban] helps the environment,” he added. “I can't plant soybeans, but I can use the same land to plant corn, rice, cotton or other crops. Why can’t I plant soybeans?”

The challenge even split the Brazilian government. Although the Justice Department says there may be evidence of anti-competitive behavior, both the Environment Ministry and the Federal Prosecutor's Office have publicly defended the moratorium.

The voluntary agreement was first signed nearly two decades ago by farmers, environmental groups and major global food companies, including commodity giants Cargill and Bunge.

It followed a campaign by environmental pressure group Greenpeace which exposed how soy grown on deforested land was being used in animal feed, including chicken sold by McDonald's.

The fast-food chain became a champion of the moratorium, with signatories pledging not to buy soy grown on lands deforested after 2008.

Before the moratorium, deforestation for soybeans and the rise of livestock farming were the main drivers of deforestation in the Amazon.

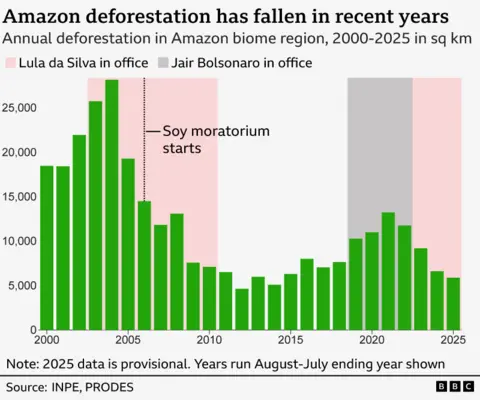

Since the agreement came into effect, deforestation has fallen sharply, reaching a historic low in 2012 during President Lula's second term.

Deforestation has increased under subsequent administrations – especially under Jair Bolsonaro, who has advocated opening forests to economic development – but has fallen again during Lula's current presidency.

Bel Lyon, chief adviser for Latin America at the World Wildlife Fund – one of the first signatories of the agreement – warned that suspending the moratorium “would be a disaster for the Amazon, its people and the world, because it could open up an area the size of Portugal to deforestation.”

Small farmers whose plots are located near soybean plantations say they disrupt local weather conditions and make it difficult to grow crops.

BBC/Tony Jolliffe

BBC/Tony JolliffeRaimundo Barbosa, who grows cassava and fruit near the town of Boa Esperanza near Santarem in the southeastern Amazon, says that when forests are cleared, “the environment is destroyed.”

“Where there is forest it's fine, but when there's no forest it gets hotter and hotter, there's less rain and there's less water in the rivers,” he told me as we sat in the shade next to the machines he uses to turn his cassava into flour.

Pressure to lift the moratorium comes as Brazil prepares to open a major new railway stretching from its agricultural heartland in the south to the rainforest.

The railroad is expected to significantly reduce transportation costs for soybeans and other agricultural products, providing another incentive to clear more land.

BBC/Tony Jolliffe

BBC/Tony JolliffeScientists say deforestation is already fundamentally changing the rainforest. Among them is Amazon specialist Bruce Fosberg, who has spent half a century studying the forest.

It rises 15 floors into a narrow tower rising 45 meters above the pristine rainforest in the heart of the Amazon. From a small platform at the top, he looks out over the green sea stretching to the horizon.

The tower is replete with high-tech instruments – sensors that monitor almost everything that happens between the forest and the atmosphere: water vapor, carbon dioxide, sunlight and essential nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

The tower was built 27 years ago and is part of a project, the Large-Scale Biosphere-Atmospheric Experiment (LBA), which aims to understand how the Amazon is changing and how close it is to a critical threshold.

The LBA data, along with other scientific research, suggests that some parts of tropical forests may be approaching a “tipping point,” after which the ecosystem can no longer maintain its own functions.

“The living forest closes,” he says, “and stops producing water vapor and therefore precipitation.”

As trees die due to deforestation, fires and heat stress, the forest releases less moisture into the atmosphere, leading to less rainfall and worsening drought, he said. This in turn creates a feedback loop that kills even more trees.

There are fears that if this continues, large areas of rainforest could die out and become savannah or dry grassland ecosystems.

Such a collapse would release enormous amounts of carbon, disrupt weather patterns on every continent and endanger millions of people, as well as countless species of plants, insects and animals whose lives depend on the survival of the Amazon.