WARNING: This article details allegations of child abuse.

A psychiatrist for a 12-year-old boy who was in the care of two Burlington, Ont., women testified that she urged the couple several times to take him to the emergency room before his death in 2022, but they refused.

The boy's health was declining and he was not eating, Dr. Shelinderjit Dhaliwal testified at the weeklong murder trial of Brandi Cooney and Becky Hamber in Milton.

“If the family had taken him to the emergency room, we wouldn't have had to go through this and the boy would be alive,” Dhaliwal said on the witness stand.

Cooney and Hamber are charged and have pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder of the boy they were trying to adopt. He is referred to in court as LL because his identity is under a publication ban to protect the name of his younger brother, known as JL.

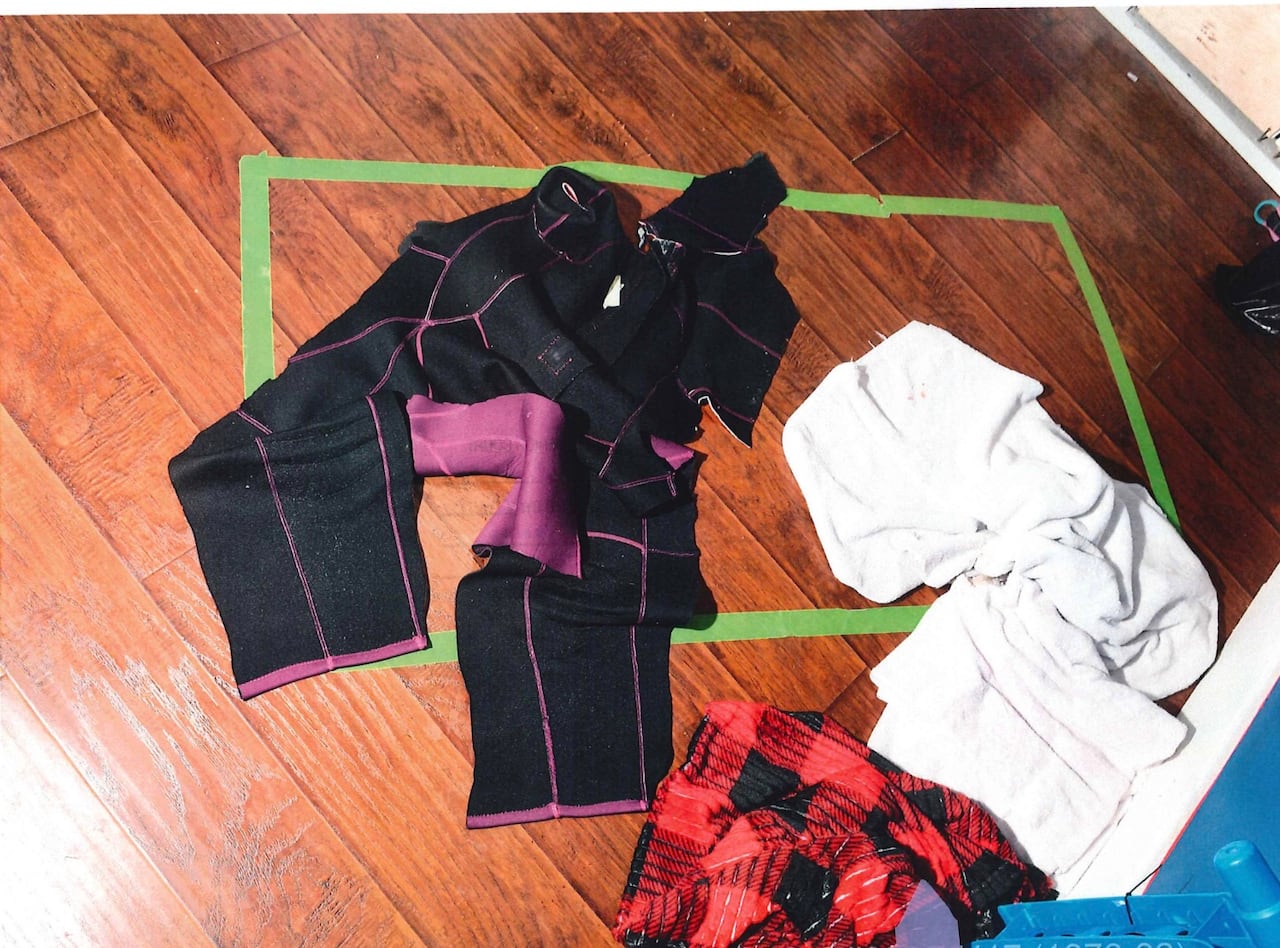

The two are also charged with confinement, assault with a weapon (bracelets) and failure to provide J.L. everything necessary for life, for which they also pleaded not guilty.

The judge-only Supreme Court trial began last month and is expected to continue until December.

The Indigenous boys, about two years apart in age, were wards of the Children's Aid Society (CAS) in Ottawa, the city where they were born. In 2017, they were moved to Burlington to live with Cooney and Hamber, who were trying to adopt them.

The trial heard from a number of doctors and therapists who saw LL and JL as patients or interacted with Humber and Cooney regarding their care. The couple claimed the boys had serious behavior problems and towards the end of LL's life he developed an eating disorder.

LL was Dhaliwal's patient from January 2022 until his death in December that year.

Paramedics found him on the cold floor of his small basement bedroom, wet, emaciated and not breathing. He soon died in the hospital. The pathologist testified he could not determine the cause of death, but could not rule out malnutrition or hypothermia.

LL was severely emaciated, weighed less than at six years old, and stopped growing. court heard.

The psychiatrist said the boy told her he was turning “fears into anger”

Dhaliwal said women brought LL to her clinic only once, in early 2022. The only time she saw him was practically in June of that year. At this meeting, Humber said, she had to lock up the food or he would “get full.”

Referring to her notes, Dhaliwal said LL told her he had difficulty expressing his emotions.

“I worry about what this day will bring,” LL’s psychiatrist quotes L.L. as saying. in June. “I turn my fears into anger.”

According to Dhaliwal, this is the last time she spoke to him directly.

Every other meeting with Humber was conducted over the phone or virtually, the psychiatrist said. During the summer and fall, Humber reported that LL's condition worsened.

By October, Humber told her LL that she was “brooding” (vomiting food) “all over the bed” every night, couldn't keep herself from eating, was peeing “all over her room” and wasn't using the camp toilet she had installed there.

In November, Humber reported that LL had “hit rock bottom” and was being cared for “like a child,” Dhaliwal said.

At every appointment, she said, she insisted that Humber and Cooney bring LL to the hospital so he could be fully assessed, monitored and quickly referred to services such as an eating disorder clinic. Dhaliwal said she explained that she was not a doctor who treated physical illnesses and that was the person he needed to see.

Each time, Humber said no because it would be too traumatic for him or he wouldn't be seen in time, Dhaliwal testified. Humber also refused to take him to the family doctor, Dr. Grim (Stephen) Duncan.

The process of sending the boy to an eating disorder clinic has begun.

That fall, Dhaliwal began the process of sending him to an eating disorder clinic, ordering blood work and other tests, the results of which were sent to Duncan. He admitted earlier this week he could have done more to intervene in LL's care, and did not see him until December 13, eight days before the boy's death.

Humber's lawyer, Monte MacGregor, pushed Dhaliwal on what she could have done differently, such as reporting her concerns to CAS. She said she didn't do this because every other patient CAS works with is the first person he contacts when child abuse is suspected.

According to Dhaliwal, CAS never contacted her.

But she stressed that she repeatedly asked Hamber and Cooney to take LL to the hospital. Instead, they waited until their next meeting with her to raise more concerns.

“What will a parent do if their child is vomiting and cannot hold anything in?” – Dhaliwal said. “I wouldn’t wait to see a psychiatrist. I would seek medical help.”

McGregor asked her why she had not referred LL to an eating disorder clinic sooner.

“It wouldn’t have saved him,” Dhaliwal replied. “The hospital would have saved him.”

If this report has affected you, you can seek mental health help through resources in your province or territory .