James GallagherHealth and Science Correspondent

BBC

BBCA therapy that would once have been considered a feat of science fiction has reversed an aggressive and incurable blood cancer in some patients, doctors report.

The treatment involves precisely editing the DNA in white blood cells to turn them into a “living drug” to fight cancer.

The first girl to be treated whose story we told in 2022is still free of the disease and now plans to become a cancer scientist.

Eight more children and two adults with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia have now been treated, with nearly two-thirds (64%) of patients in remission.

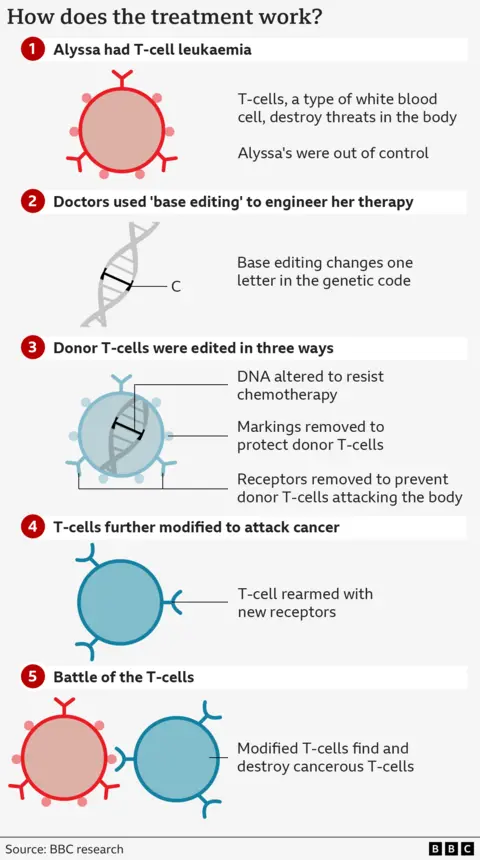

T cells are supposed to be the body's guardians, identifying and destroying threats, but in this form of leukemia they run out of control.

For those in the trial, chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation were unsuccessful. Short of experimental medicine, the only option was to make their deaths more comfortable.

“I really thought I was going to die and not be able to grow up and do everything every child deserves,” says 16-year-old Alyssa Tapley from Leicester.

She was the first person in the world to be treated at Great Ormond Street Hospital and is now enjoying life.

The revolutionary treatment three years ago involved destroying her old immune system and creating a new one. She spent four months in hospital and was unable to see her brother for fear he would contract an infection.

But now her cancer is undetectable and she only needs annual checkups. Alyssa is taking her A-levels, winning the Duke of Edinburgh's Award, taking driving lessons and planning her future.

“I'm going to do a biomedical internship and hopefully one day do blood cancer research,” she said.

The team from University College London (UCL) and Great Ormond Street Hospital used a technology called base editing.

Basics are the language of life. Four types of bases—adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T)—are the building blocks of our genetic code. Just as the letters of the alphabet form words that carry meaning, the billions of bases in our DNA form the instructions for our body.

Base editing allows scientists to zoom in on a specific part of the genetic code and then change the molecular structure of just one base, converting it from one type to another and rewriting the instruction manual.

The researchers wanted to harness the natural power of healthy T cells to seek out and destroy threats and turn it against T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

This is no easy feat. They had to create good T cells to hunt the bad ones without killing off the treatment.

They started with healthy T cells from a donor and proceeded to modify them.

The first base change disabled the T cell targeting mechanism so that they could not attack the patient's body.

The second removed the CD7 chemical markings that are found on all T cells. Its removal is necessary to prevent self-destruction of the therapy.

The third modification was an “invisibility cloak” that prevented the chemotherapy drug from killing cells.

The final stage of genetic modification caused the T cells to hunt for anything labeled CD7.

Now the modified T cells will destroy all other T cells found, be they cancerous or healthy, but they will not attack each other.

The therapy is given to patients and if the cancer cannot be detected after four weeks, patients undergo a bone marrow transplant to restore the immune system.

“A few years ago this would have been science fiction,” says Professor Wasim Qasim of UCL and Great Ormond Street.

“We have to essentially dismantle the entire immune system.

“It's a deep, intensive treatment and it's very demanding on patients, but when it works, it works very well.”

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, reported the results of the first 11 patients treated at Great Ormond Street and King's College Hospital. The results show that nine people achieved deep remission, allowing them to undergo bone marrow transplantation.

Seven of them remain healthy for a period ranging from three months to three years after treatment.

One of the biggest risks of treatment involves infections while the immune system is destroyed.

In two cases, the cancer lost its CD7 marking, allowing it to escape treatment and return to the body.

“Given how aggressive this particular form of leukemia is, these are quite remarkable clinical results and obviously I'm very pleased that we have been able to give hope to patients who would otherwise have lost it,” said Dr Robert Chiesa, from the bone marrow transplant unit at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Dr Deborah Yallop, consultant haematologist at King's, said: “We have seen impressive results in treating leukemia that seemed incurable – this is a very powerful approach.”

Commenting on the study, Dr Tanya Dexter, senior medical officer at UK stem cell charity Anthony Nolan, said: “Given that these patients had a low chance of survival before the study began, these results give hope that similar treatments will continue to be developed and become available to more patients.”