Before flowers appeared, these plants used heat to attract insects

New study of strange cycad plants provides insight into the prehistoric origins of pollination

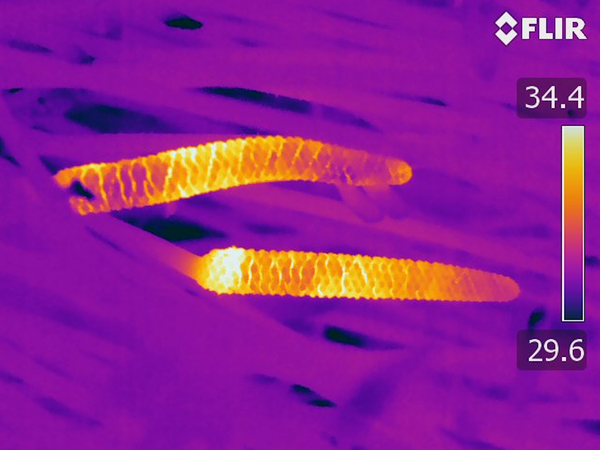

Thermal image of two male cycad cones. Zamia furfuracea. The buds heat up as they release pollen. Certain areas of the buds may heat up differently, and these patterns serve as guides for pollination.

The words “pollination” and “flower” may seem inseparable, but plants began courting insects millions of years before they evolved. bright petals. Now we know how they could do it: not with dazzling color, but with radiant heat.

The study, published today in Science shows that cycads, tropical plants that resemble palms, attract beetles using infrared radiation generated by their cone-shaped reproductive structures. Given that cycads are the world's oldest group of animal-pollinated plants, co-senior author Nicholas Bellono, a molecular biologist at Harvard University, says the findings provide a window into the “earliest form of pollination” – a prototype for what is today one of the most transformative ecological interactions on Earth.

Cycads are thermogenic, meaning they produce some serious heat—some species reach temperatures up to 15 degrees Celsius (27 degrees Fahrenheit) above ambient temperatures. Wondering why they would waste so much energy, lead author Wendy Valencia-Montoya, Ph.D. A student in Bellono's lab designed an experiment: She smeared cycad cones with an ultraviolet fluorescent dye so that incoming beetles would become coated in it and leave visible marks on the next cone they touched. In the new paper, she and her colleagues found that the beetles preferentially visit the warmest areas of the buds.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Beetles of the species Ropalotria furfuracea on the men's cone Z. furfuracea, whose cones produce heat during pollination.

Researchers have established other functions of cycad thermogenesis: heat increases humidity and dispels odorboth are important pollination signals, and this creates a cozy refuge for the beetles to mate and reproduce. But this work suggests that infrared light itself serves as a direct signal. Indeed, when the researchers heated 3D-printed cycad buds and covered them with plastic film to prevent heat conduction when touched, making infrared radiation the only possible heat signal, the beetles were still attracted to them through the unheated buds.

To figure out how the beetles pick up what the cycads lay down, the team analyzed the insects' sensory organs for heat-sensitive structures and found that the antennae tips were loaded with TRPA1, a heat-activated ion channel that also helps snakes And mosquitoes perceive infrared radiation. For both beetle species tested in the study, TRPA1 activation was finely tuned to the temperature range of the respective host plant. The scent that travels further likely directs the beetles to the desired area, but infrared radiation appears to be the final beacon guiding them there.

These discoveries also relate to a long-standing evolutionary mystery, which Charles Darwin called “the riddle of evolution.”disgusting secret»: How did the flowering plants known as angiosperms rapidly expand to an estimated 350,000 species, while cycads and other gymnosperms barely number in the thousands? authors of the accompanying commentary suggest that the use of infrared radiation may have limited the number of insects with which cycads could build specialized relationships. While flowering plants can adjust hue, saturation and pattern, creating an almost infinite number of combinations for different pollinators, cycads can only adjust the intensity of heat.

Irene Terry, a plant biologist who studies cycad pollination at the University of Utah and was not involved in the study, calls it “one of the best, if not the best, articles on cycads I've ever read.” In terms of evolutionary history, she notes, cycads may also have had different scent-producing compounds to diversify and establish relationships with specific pollinators, just as flowers do. Cambridge University plant biologist Beverly Glover, a co-author of the paper, agrees, but adds that angiosperms have the best of both worlds—smell and color. “Several opportunities for diversification are probably better than one,” she says.

The dependence on detectable temperature also raises a conservation question: could global warming make it more difficult for beetles to recognize the warmth of their hosts? The cycads are already the most dangerous plant order, and behavioral ecologist Sean Rands of the University of Bristol in England, who was not involved in the study, says the prospect of disruption adds to the list of threats. “Any information you take away,” he says, “will make pollination more difficult.”

It's time to stand up for science

If you liked this article, I would like to ask for your support. Scientific American has been a champion of science and industry for 180 years, and now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I was Scientific American I have been a subscriber since I was 12, and it has helped shape my view of the world. science always educates and delights me, instills a sense of awe in front of our vast and beautiful universe. I hope it does the same for you.

If you subscribe to Scientific Americanyou help ensure our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on decisions that threaten laboratories across the US; and that we support both aspiring and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return you receive important news, fascinating podcastsbrilliant infographics, newsletters you can't missmust-watch videos challenging gamesand the world's best scientific articles and reporting. You can even give someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in this mission.