Ancient bees buried in bones reveal fossils

Bones of now-extinct species became shelters for baby bees thousands of years ago, scientists report in a first-of-its-kind discovery.

Illustration by Jorge Machuca

Thousands of years ago, in what is now the Dominican Republic, there was a cave full of bones. And these bones were full of bees.

For the first time in paleontology, researchers discovered that bees used the jaws of now-extinct mammals as burrows.. It is unclear what species of bees took advantage of this terrible opportunity – only their smooth-sided nests remained, located in the dental pockets of ancient rodents and sloths. But this behavior has never been documented before, says Lázaro Viñola López, a research fellow at the Florida Museum of Natural History and one of the discoverers. “It was something completely unexpected,” he says.

When Viñola Lopez and his colleagues crawled past the jagged entrance to a cave called Cueva de Mono, they were hunting for fossilized lizards, which they found in abundance. They also found tens of thousands of bones of extinct rodents and sloths, leading them to believe they had stumbled upon the kill site of an ancient family of owls that had likely nested in the cave and regurgitated bones on the cave floor. Although it is difficult to precisely date the fossils, the species come from the late Quaternary period, which began 125,000 years ago, and include species that went extinct more than 4,500 years ago, researchers reported Tuesday in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

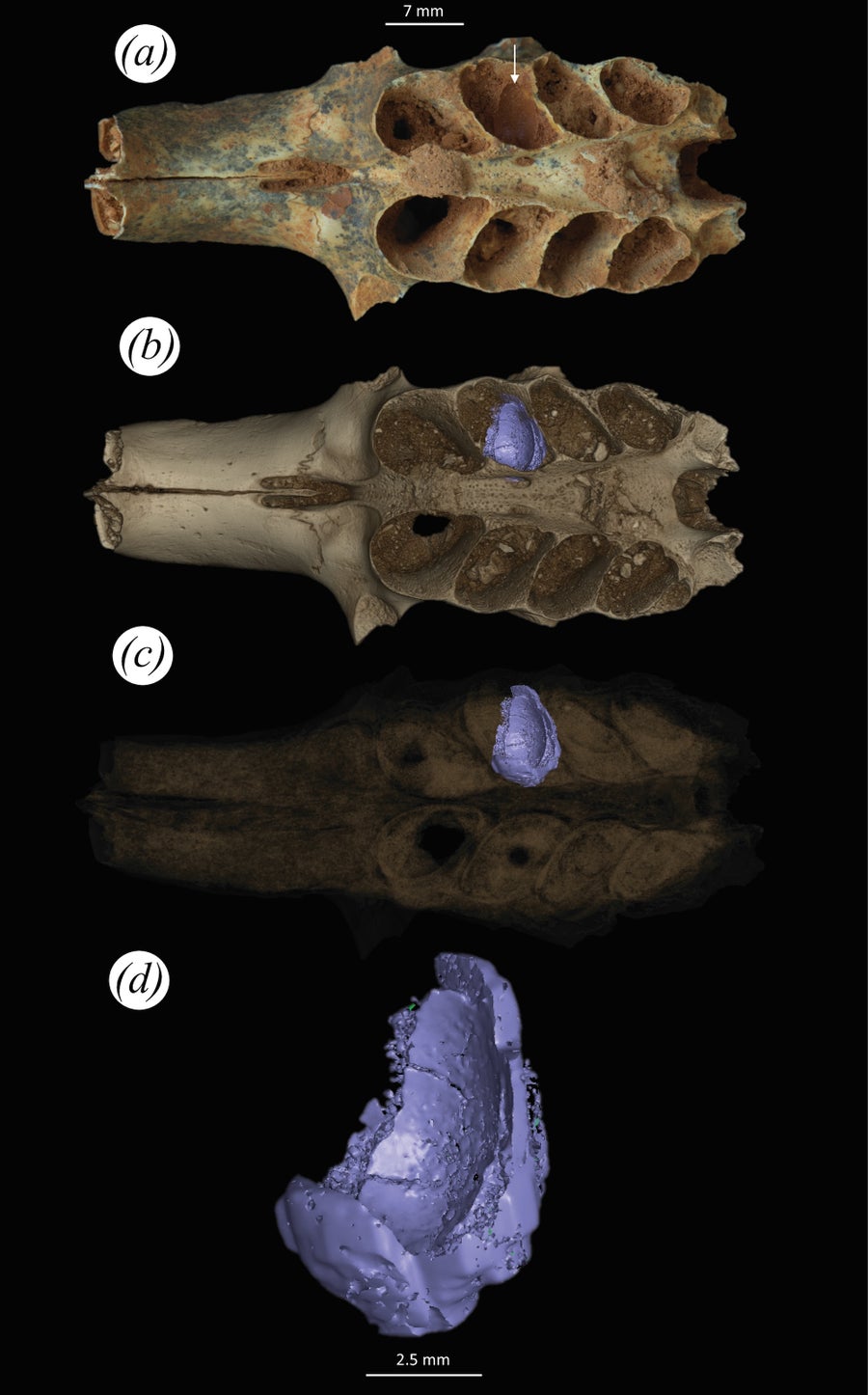

From the article “Trace fossils in mammal remains reveal new nesting behavior of bees” by Viñola Lopez et al. Royal Society Open Science 12; December 16, 2025 (CC BY 4.0)

In the mud that filled the empty jaws of rodents and sloths, Vignola Lopez and his colleagues noticed strange, smooth, cup-shaped structures that they eventually realized were created by bees. The hard, smooth walls were the result of a waterproof layer that solitary bees add to their brood cells where insect larvae develop.

More than 90 percent of bee species are solitary, and most of them dig burrows in the ground. “As far as I know, modern bees don't nest in caves, and they don't nest in these sediment-filled bone cavities,” says Anthony Martin, a paleontologist at Emory University who was not involved in the study but examines fossils and burrows and tracks left by ancient animals. He called the discovery a “two-for-one surprise.”

Vignola Lopez and his colleagues suspect that the bees used the bones soon after the owls regurgitated them, and this may have happened because the soils in the surrounding forests were thin.

Paleontologists working in a cave on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola have discovered the first known case of ancient bees nesting inside pre-existing fossil cavities.

Illustration by Jorge Machuca

Bones filled with bee nests were found in three of the four layers of soil, suggesting that bees had been using the cave for a long period of time. There are also cavities of single teeth filled with up to six different sockets. “It’s probably a few bees that come and nest together,” says Vignola Lopez.

The bones may have provided additional protection against predators such as parasitic wasps.

“It’s kind of like a thermos,” Martin says. “They had an outer protective layer that the bone provided, and then they had a brooding cell that was in the sediment, so they had double protection.”

It's time to stand up for science

If you liked this article, I would like to ask for your support. Scientific American has been a champion of science and industry for 180 years, and now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I was Scientific American I have been a subscriber since I was 12, and it has helped shape my view of the world. science always educates and delights me, instills a sense of awe in front of our vast and beautiful universe. I hope it does the same for you.

If you subscribe to Scientific Americanyou help ensure our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on decisions that threaten laboratories across the US; and that we support both aspiring and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return you receive important news, fascinating podcastsbrilliant infographics, newsletters you can't missvideos worth watching challenging gamesand the world's best scientific articles and reporting. You can even give someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in this mission.