Joan Brugge, PhD, in her office at Harvard Medical School. “I can't stop just because of the difficulties we're facing right now,” says Brugge. “We all need to work hard to make a difference for cancer patients and their families. This applies to everyone.”

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

hide signature

switch signature

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

In a cancer research laboratory on the Harvard Medical School campus, two dozen small jars with pink plastic lids sit on a metal counter. Inside these unassuming-looking jars lies the essence of Joan Brugge's ongoing multi-year research project.

Bruges picks up one of the jars and looks at it in awe. Each jar contains samples of breast tissue donated by patients following tissue biopsies or breast surgery—samples that could lead to a new way to prevent breast cancer.

Brugge and her research team analyzed the cellular structure of more than 100 samples.

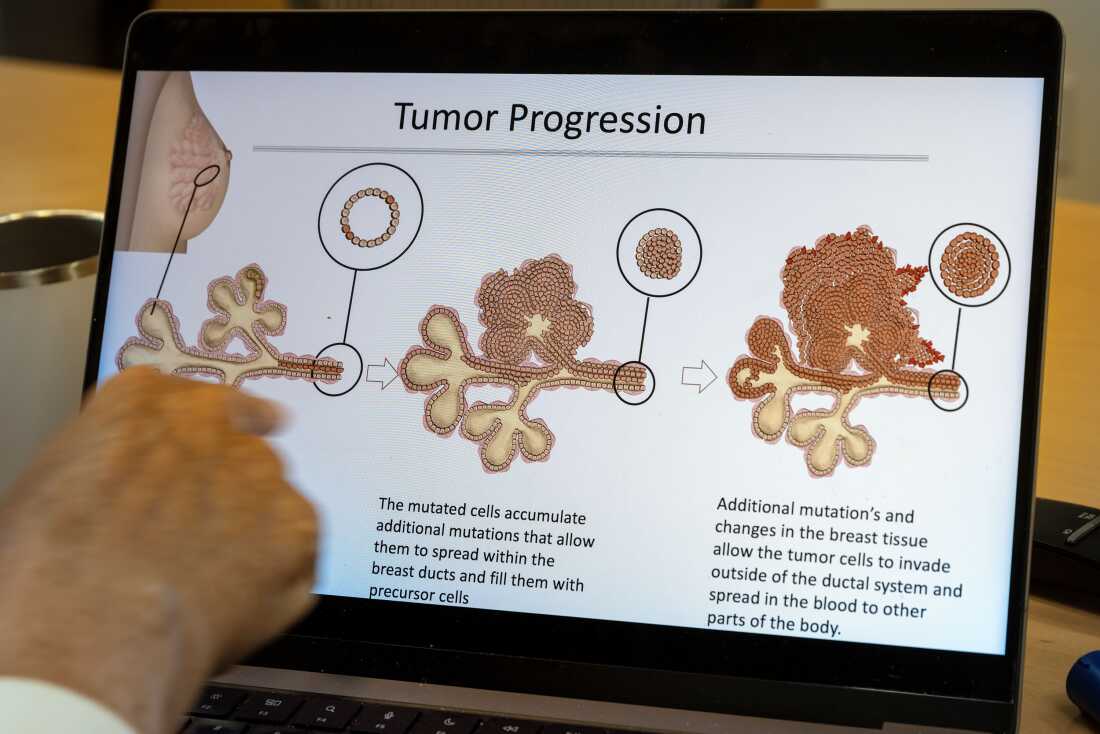

Using powerful microscopes and sophisticated computer algorithms, they describe every stage of breast cancer development, from the first signs of cell mutation to the formation of tiny clusters, long before they become large enough to be considered tumors.

Their goal is to prevent breast cancer, a disease that affects about one in eight women in the United States, as well as some men. Their ultimate goal is to relieve the pain, suffering and risk of death that accompany this disease. And their painstaking work, unwinding in six years out of a seven-year plan, $7 million federal grantgave results.

At the end of 2024, Bruges and her colleagues identified specific cells in breast tissue containing genetic seeds of breast tumors.

And they found that these “seed cells” were surprisingly common. In fact, they are present in normal, healthy tissue in every breast sample her lab has examined, Brugge says, including samples from patients who never had breast cancer but who had surgery for other reasons, such as a breast reduction or a biopsy that turned out to be benign.

Joan Brugge holds several breast tissue samples that are part of a multi-year Harvard Medical School research project funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute.

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

hide signature

switch signature

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

The Bruges lab's next research challenge is clear: find ways to detect, isolate and destroy mutant cells before they have a chance to spread and form tumors.

“I’m excited about what we’re doing now,” Brugge says. “I think we could make a difference, so I don’t want to stop.”

But this year, work at the Bruges laboratory has slowed down significantly. In April her $7 million breast cancer research grant Money from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was frozen, along with all federal money given to Harvard researchers.

The Trump administration said it was withholding funds. regarding the university's fight against anti-Semitism on campus.

Some Bruges laboratory employees lost federal scholarships that financed their work. Brugge told others funded by the NIH grant that she could not guarantee their salaries. In total, Bruges lost seven of its 18 laboratory employees.

In September, the NIH grant funding stream was restored. But in recent months, the Trump administration has said that Brugge and other Harvard researchers not allowed apply for the next round of multi-year grants.

Federal Judge lifted this banbut Club Brugge missed the deadline to apply for an extension. So its current funding will end in August.

Joan Brugge discusses a photo from a gene testing experiment with a colleague in her lab at Harvard Medical School.

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

hide signature

switch signature

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

Club Brugge struggled to obtain private funding from foundations and philanthropists. She then managed to restore two positions for at least a year, but job applicants are wary of her.

In the United States, the future of federal funding for cancer research remains uncertain.

President Trump proposed NIH budget cuts nearly 40% in 2026, the current fiscal year.

IN budget messageThe White House said that “NIH has undermined the trust of the American people through wasteful spending, misleading information, risky research, and promotion of dangerous ideologies that undermine public health.”

But Congress has other plans: Home budget plan includes a $48 million increase that will bring The NIH budget will be $46.9 billion.. Senate The plan would add $400 million, including an additional $150 million for cancer research.

However, differences between all proposed budgets remain unresolved.

Joan Brugge uses graphics to explain the three stages of breast tumor progression.

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

hide signature

switch signature

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

At the same time, such defenders as Mark Fleury With American Cancer Society reminds legislators that federally funded research contributes to the decline in cancer deaths 34% since early 1990s and that some of the credit for this goes to federally funded research advances.

“But we still have an incredible way to go before we can say we've changed the trajectory of cancer,” Fleury told NPR. “There are still types of cancer that are quite deadly, and there are still groups of people whose experience of cancer is very different from other groups.”

Cuts in research funding will have a direct impact on patient treatment options, Fleury said. For example, cutting the NIH budget by 10% would ultimately result in two fewer new drugs or treatments per year, according to projection from the Congressional Budget Office.

Recent study looked at drugs that were developed through NIH-funded research and approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 2000. More than half of these drugs likely would not have been developed if the NIH operated on a 40% smaller budget.

“We cannot say: “But for this grant [specific] the drug would not have been born,” says Pierre Azoulayco-author of the study and professor at MIT. But overall, fewer drugs would reach the market, he says. “It makes us at least want to stop and ask, 'What are we doing here?' Are we shooting ourselves in the foot?”

In the midst of all this uncertainty, Bruges finds it difficult to focus on her goal of finding new ways to prevent breast cancer.

Laboratory research tray in the Bruges Laboratory at Harvard Medical School.

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

hide signature

switch signature

Robin Lubbock/WBUR

Today, she spends about half her time searching for new sources of funding, dealing with the concerns of remaining staff and keeping up with the latest news about Harvard, the Trump administration, the NIH and other federal agencies that have faced grant freezes, staff layoffs and other disruptions.

She would rather return to the ongoing investigations, which she is confident will ultimately save lives.

The Bruges lab failure highlights another problem: The United States is kneecapping the next generation of cancer researchers. Her collaborators included staff scientists, postdocs, and graduate students. Of the seven people who left the lab this year, one left the United States, one took a job at a healthcare management company, four went back to school, and one person is still looking for work.

One of Brugge's former employees is Y, a computational biologist. She helped develop and launch a tool that analyzes millions of breast tissue cells from samples in pink-topped jars.

Y moved to Switzerland in October to begin research and complete his PhD. program. (NPR agreed to identify her only by her initials because she plans to return to the U.S. to attend academic conferences and worries that speaking out could affect future visas.)

“I thought the U.S. would be a safe place for scientists to study and grow,” said Y, who moved to Boston from abroad to pursue a master’s degree in bioinformatics at Harvard. “I really hope that those who have the opportunity to study this further will be able to fill in the missing pieces in cancer research.”

Bruges no longer accepts job applicants from outside the U.S., even if they are top candidates, because it can't afford to pay the Trump administration. new fee of $100,000 about visas for foreign researchers.

Association of American Universities and US Chamber of Commerce filed a lawsuitclaiming that the fee is erroneous and illegal. The Trump administration said the fee would be discourage the use of foreign workers and improve opportunities for Americans.

Bruges doubts that work in her lab will ever return to normal.

“This existential threat to research will always exist,” says Brugge. “I would definitely be concerned because we don’t know what will happen in the future that could trigger these types of actions.”

Brugge was considering closing her laboratory. But it still hires employees whose future scientific careers depend on completing some research. And when she looks at those pink-lidded jars, she still sees a promising sight.

This story comes from NPR's health reporting partnership with VBUR And KFF health news.