The way people deal with death and the rituals we build around it are an important part of our identity. The practice of burial may date back hundreds of thousands of years and began shortly after our ancestors left the trees. However, cremation is a completely different story. Burning the dead requires planning, fuel, and coordinated labor, making the practice a rare and complex practice in early human history.

A new discovery from northern Malawi changes this picture. Researchers from the US, Africa and Europe have found evidence of a cremation pyre dating back about 9,500 years, the earliest known example of intentional cremation ever discovered in Africa. Published in Achievements of scienceThe study suggests that ancient hunter-gatherers practiced more complex ritual behavior than scientists assumed.

Read more: Life after death: what burial options will look like in a sustainable future

Reconstruction of a 9,500-year-old cremation

Mountain Mountain

Photo courtesy of Jacob Davis

The cremation took place at Chora 1, a site at the base of a granite cliff rising hundreds of feet above the surrounding plains. Previous research has shown that people lived here as early as 21,000 years ago. buried their dead approximately between 16,000 and 8,000 years ago. When we looked closer, we discovered something else: ash.

Sediment analysis revealed highly fragmented remains of one individual. There is no evidence that anyone else was cremated there before or since. The remains were those of an adult female, between 18 and 60 years of age, standing just under five feet tall. The nature of the heat damage indicates that her body was burned shortly after death, before decomposition began.

One absence was striking. “Surprisingly, there were no tooth or skull fragments in the fire,” study co-author and bioarchaeologist Elizabeth Sawchuk said in the journal. press release. “Because these body parts are usually preserved during cremation, we believe the head may have been removed before burning.”

Rare practice in human history

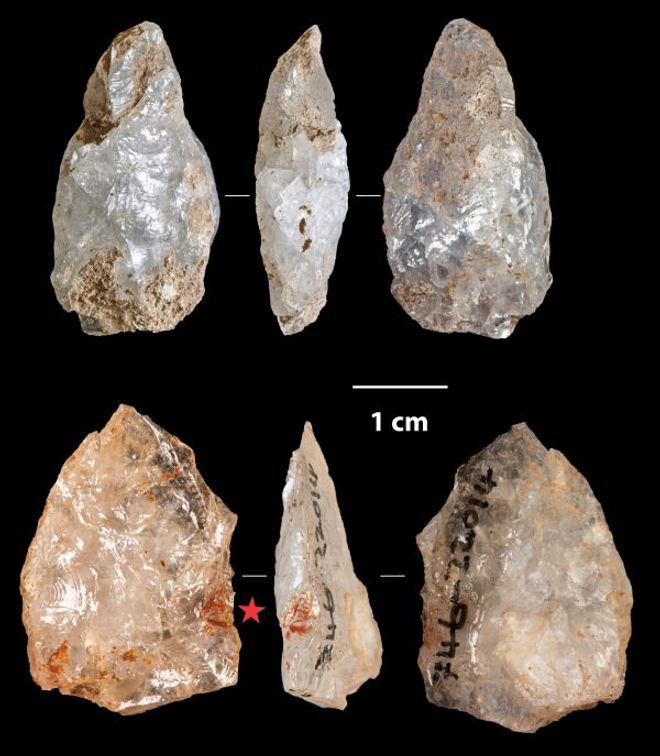

Bonfire glasses

Image courtesy of Justin Pargeter

Cremation itself is nothing new, but intentionally constructed pyres are rare in the archaeological record. Burnt human remains appeared as early as 40,000 years ago at Lake Mungo in Australia, but clear evidence of bonfires appeared much later.

The oldest known fire in Alaska dates back to approximately 11,500 years ago and contains the remains of a small child. In Africa, definitive cremations were previously known only about 3,500 years ago and were associated with Neolithic pastoral herders rather than hunter-gatherers.

Cremation is a rather labor-intensive event that usually occurs much later in human history, most often in food producing societieswhich tend to have more sophisticated technologies. For mobile hunter-gatherers, the need for labor and fuel would have made cremation an impractical choice, making the discovery at Chora 1 particularly surprising.

An unusual woman and a memorable place

The fire required significant public effort. Researchers estimate it's at least 65 pounds. materials were collected to start the fire. The stone tools found in the pyre may have been deliberately placed as funerary objects.

“Cremation is very rare among ancient and modern hunter-gatherers, at least in part because pyres require enormous amounts of labor, time and fuel to reduce a body to fragmented and burned bones and ash,” lead author Jessica Cerezo-Roman, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma, said in a press statement.

The importance of this site did not end with cremation. Centuries before this event, large bonfires were lit there, and 500 years after that, people returned to light more fires right at the stake. Although no one else was cremated, the place was clearly remembered.

Why this woman was treated in such a peculiar way remains unknown.

“Why was this woman cremated when other burials at this site were not treated in this manner?” senior author Jessica Thompson of Yale University said in a press release. “There must have been something special about her that required special treatment.”

Read more: Hidden molecular clocks in larvae may alter forensic estimates of time of death

Article sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed research and high-quality sources for their articles, and our editors review scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: