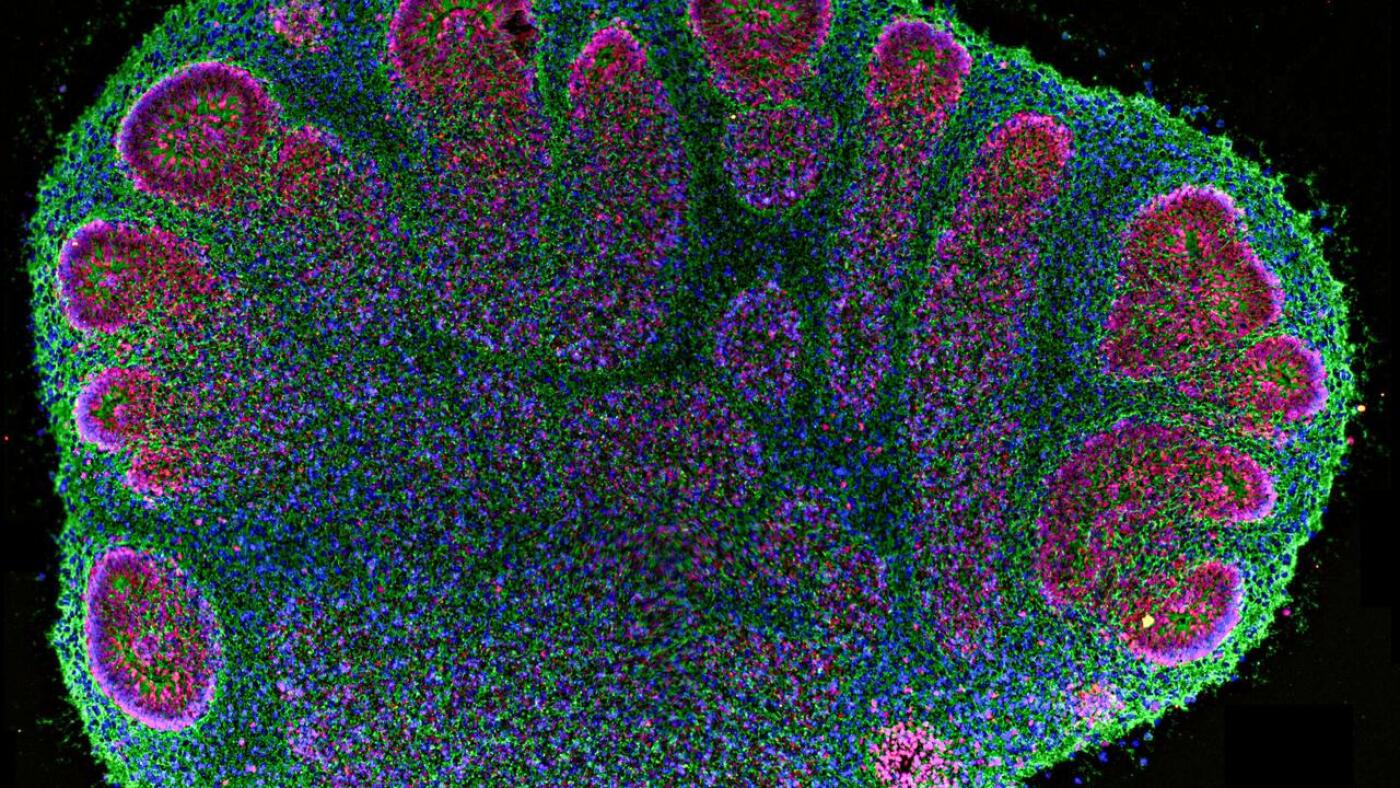

Cross section of a two-month-old cerebral organoid under a fluorescence microscope.

Pasteur Institute-SupBiotech/NASA

hide signature

switch signature

Pasteur Institute-SupBiotech/NASA

Research into diseases such as autism, schizophrenia and even brain cancer increasingly relies on clusters of human cells called brain organelles.

These pea-sized pieces of neural tissue model aspects of human brain development as they grow in the laboratory over months or even years. They also cause anxiety for many people, in part because the brain is so closely connected to our sense of self.

A group of scientists, ethicists, patient advocates and journalists. met for two days this fall in Northern California to discuss how scientists and society should act.

Among the questions:

- Is it possible to place human organoids in the brain of an animal?

- Can organoids feel pain?

- Can they become conscious?

- Who, if anyone, should regulate this research?

“We are talking about an organ that is located in the seat of human consciousness. This is the place of personality and who we are,” says Insoo Hyuna bioethicist from the Museum of Science in Boston who attended the meeting.

“So it makes sense to be especially careful with the experiments we do,” he says.

Social problems by the sea

The event was held Dr. Sergiu Pascadistinguished organoid researcher whose laboratory at Stanford University used this technology to develop potential treatment for a rare cause of autism and epilepsy.

Organoids allow scientists to study brain cells and circuits that are not found in animals. – says Paska.

“For the first time, we have the opportunity to really work with human neurons and human glial cells,” he says, “and ask questions about these really mysterious brain diseases.”

But Pashka's work sometimes caused public concern because his laboratory recreated the path of human painAnd transplanted human organoid into the rat brain.

“Of course there are issues of ethics, social implications and religious views that need to be taken into account,” he says. Many of these issues were outlined in a recent report article Paska and others in the magazine Science.

To take the next step, Pashka invited the group to the Asilomar Convention Center on the Monterey Peninsula. This is the place where 50 years ago another group met to discuss the first ethical principles for genetic engineering.

The organizers of the organoid event had more modest expectations.

“Our goal for this meeting was just to get everyone from all of these areas together and start brainstorming,” Paschka says.

It has happened—at formal meetings, coffee breaks, after-hours social gatherings, and even while walking on the beach. Participants presented a variety of points of view.

Risk vs reward

Scientists and patient advocates at the meeting often emphasized the need to quickly answer questions and find cures.

Bioethicists have spoken more frequently about the importance of restrictions to ensure that people consent to having their cells turned into organelles, and to thwart any attempts to improve the brains of animals or humans.

However, there was consensus on the need to keep the public informed.

When people hear about brain organoid research, they tend to have one overarching and reasonable question for the scientists, he says. Alta CharoProfessor Emeritus of Law and Bioethics, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

“How far have they come in making organoids that can actually replicate what we associate with human abilities?” she says. “Have we reached a point where we are worried?”

Not yet, probably. But now that prospect appears closer as scientists link multiple organelles to create more brain-like structures called assembleloidsMy voice.

For example, Paska's team created a network of four organoids to model the pathway through which pain signals are delivered to the brain.

That sounds alarming, Charo says, until you realize that this network of cells lacks the circuitry to feel pain.

“I think the mere existence of a pain pathway is enough to create a public perception problem that an organoid or assembly is suffering,” says Charo. “And yet, if the path that allows for this emotional aversion does not exist, then there is no suffering.”

And no ethical issues at the moment.

Even so, she said, researchers and regulators should probably look ahead rather than wait until there is a real problem.

Problem of perception

Some participants accused the media of glossing over the current limitations of organoids and describing these clusters of cells as “mini-brains.”

Such coverage has led some people to mistakenly believe that there are laboratories in which “the brain grows in a Petri dish,” says Dr. Guo-li Mingorganoid researcher at the University of Pennsylvania.

Scientists need to challenge this notion and explain how organoid research helps people with life-threatening diseases, Ming says.

Her own laboratory, for example, is working to tailor treatments for brain cancer using organoids derived from a patient's own tumor cells. This allows doctors to ensure that a cancer drug effectively targets a patient's specific tumor.

Ming also thinks it's too early to worry about organoids becoming conscious because “we're a long way from mimicking the brain activity of real people.”

Despite this, organoid scientists “definitely need some guidance,” Ming says, due to current public concerns and the possibility of inappropriate research in the future.

New cells, old problems

The ethical and social concerns surrounding brain organoids echo those surrounding stem cell research more than 20 years ago.

At the time, there were concerns that neural stem cells could give animals cognitive abilities similar to humans.

It turned out that these human cells do not do well in the brain of another species. But organelles that were originally stem cells can thrive in animals' brains and even become integrated into their circuitry.

“So what used to be a very hot issue in stem cell research is now back,” says Hoehn.

Hoehn was part of a group that worked on organoid guidelines for the International Society for Stem Cell Research five years ago, when the need for oversight seemed less urgent.

“We had the attitude of, let's wait and see,” he says, because it was unclear how long it would take for organoid technology to become relevant. “We got down to business pretty quickly.”

Hoehn's immediate concern is protecting experimental animals from organoid experiments that could cause suffering. But in the long term, he said, guidelines and government oversight may be needed to ensure organoid research doesn't harm or horrify people.

The Asilomar meeting suggests that many scientists know this and want to help navigate this new scientific frontier.