When you make a purchase through links in our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

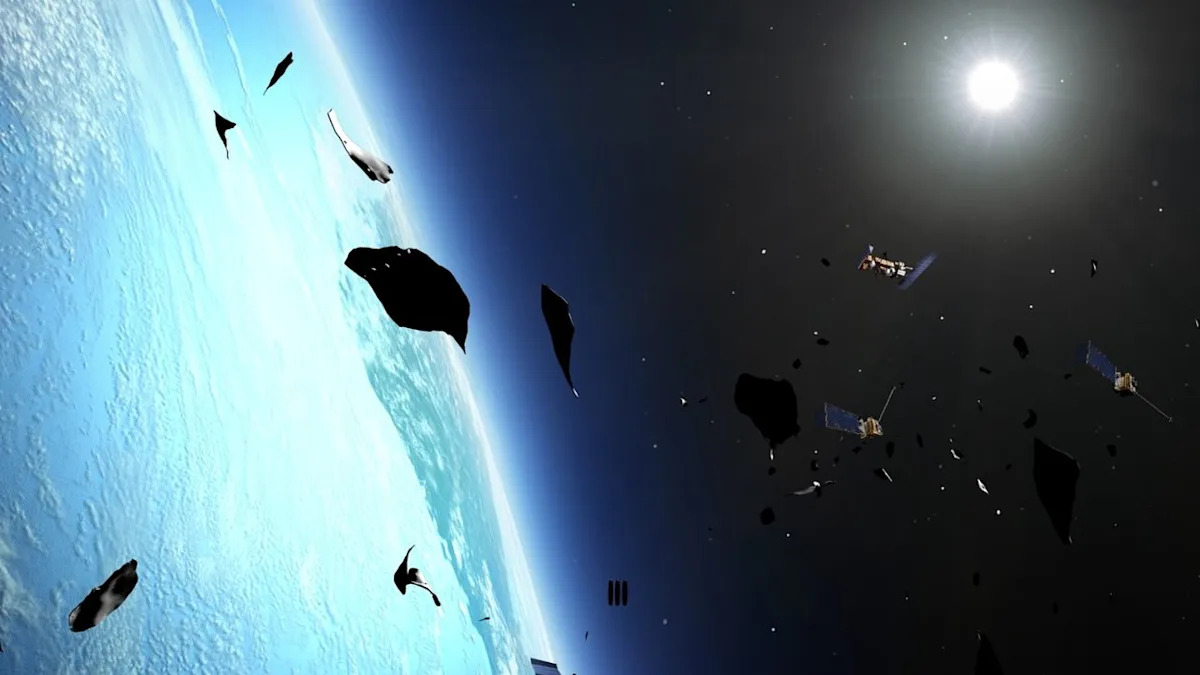

Illustration of space debris in orbit. | Photo: Mark Garlick/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

The Earth is surrounded by man-made debris that orbits our planet. The problem is getting worse every year, and 2025 is no exception.

Space debris experts say there are about 130 million pieces of orbital debris floating around our planet: high-velocity debris from rocket stage explosions, abandoned satellites, and debris and pieces of debris from space deployments. Part of this tortuous mess is the result deliberate destruction of a spacecraft by testing anti-satellite weapons.

All this cosmic clutter means an increased risk of collisions that create even more debris – better known as Kessler syndrome. This cascading effect was described in detail back in 1978 by NASA scientists Donald Kessler and Burton Cours-Palais in the seminal space physics paper “Collision Rates of Artificial Satellites: Creation of the Debris Belt.” 47 years later, the problem has only gotten worse, and as several debris impact incidents this year show, we still don't have a good way to solve or even slow down the buildup of orbital debris around our planet.

The impact of the debris caused an emergency launch

As the Chinese Shenzhou 20 astronauts prepared to undock from the Chinese space station on November 5, the crew discovered that their spacecraft Tiny cracks appeared in the porthole. The reason given was the external impact of space debris, which made the ship unsuitable for the safe return of the crew.

This incident required the first abort mission in the Chinese human spaceflight program; there was an unmanned spacecraft “Shenzhou-22” with cargo. launched November 25.

The Shenzhou saga ended happily with Chinese astronauts return safely to Earth aboard the Shenzhou 21 spacecraft. This was the first alternative reentry procedure activated in the history of the Chinese space station program.

The commander of the Chinese ship Shenzhou 20, Chen Dong, greets the crowd. | Photo: VCG/Getty Images

However, the Shenzhou 20 landing delay is not just a procedural footnote. “This is a signal about the state of our orbital commons,” said Moriba Jha, a space debris expert and professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

“The crew's return was delayed because microscopic debris damaged the spacecraft's window,” Jha told Space.com. “This decision to delay and replace vehicles reflects responsible risk management based on incomplete knowledge. It also exposes a deeper problem. Namely, our collective inability to maintain a constant, verifiable understanding of what is moving in orbit,” he said.

Every fragment we leave up in the air, Jha said, “exacerbates the rising tide of uncertainty.”

Required: Data accuracy and transparency

According to Jha, this uncertainty is not just statistical, but epistemic. “When the rate at which uncertainty increases exceeds the rate at which knowledge is updated, margins of safety erode,” advocating the development of missions, command structures and information systems that “recover knowledge faster than it erodes,” he said.

The cracked window of the Shenzhou 20 spacecraft, Jha said, “follows gaps in global tracking, attribution and accountability. Until countries and companies treat data accuracy and transparency as part of safety practices, dangerous situations like this will continue to happen.”

China's decision to delay the manned Shenzhou's re-entry into the atmosphere until its engineers were confident in the assessment “was an act of epistemic humility—recognizing what was unknown and adjusting accordingly.” Such humility must be systematized, not exclusive,” he said.

In practice, Jha said, the Shenzhou 20 episode should push the international community toward verifiable management—that is, common baselines of orbital situational awareness, interoperable knowledge graphs, and certification programs that recognize that missions restore order rather than add risk.

“Only by aligning engineering, political and information ethics can we prevent ‘ordinary’ anomalies from becoming harbingers of disaster,” Jha said. “If we learn the right lesson, this will be remembered not as a lucky escape but as a turning point,” he said, adding that “the evidence is that safety in orbit begins with honesty about what we do and don't know, and a willingness to regain knowledge faster than we lose it.”

Ignoring long-term consequences

Darren McKnight – Senior Technical Researcher LeoLabsgroup dedicated to space awareness.

For McKnight, the biggest challenges in 2025 were:

-

The proliferation of satellite constellations, some of them treating Starlink, Iridium and OneWeb responsibly, and some treating China's Thousand Sails megaconstellation and its Gowang satellite Internet payload responsibly, leaving rocket bodies at high speed and high altitudes and not working with other constellations to “show your work, share your work and understand the context.”

-

Leaving the rocket bodies in orbit will last more than 25 years. The good news is that the potential for debris in low Earth orbit can be reduced by 30% by removing the 10 most statistically concerning objects. The bad news, however, is that the world community is abandoning missile bodies at an accelerating pace, despite the known negative long-term consequences of doing so.

“Some low-Earth orbit operators ignore the known long-term consequences of behavior for short-term gain,” McKnight said. In his opinion, the situation is similar to the early stages of global warming.

“Some won’t change their behavior until something bad happens.” McKnight concluded.

Risks and liability

Another voice of concern is the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). It came out this month.”Space protection: environmental problems, risks and responsibilitiesThis document refers to a number of issues related to space debris as “emerging issues.”

In an era of increasing global launches, fueled by a decisive approach to launching constellations of megasatellites into Earth orbit, there is also growing concern about the consequences of re-entering the atmosphere of failed space equipment. | Photo: Chelsea Thompson/NOAA.

“The space sector is growing exponentially, with more than 12,000 spacecraft deployed over the past decade and more planned as the world takes advantage of satellite services. This growth creates serious environmental problems in all layers of the atmosphere,” the document explains.

UNEP specifically notes air pollution from launch emissions, spacecraft emissions into the stratosphere, as well as the re-entry of space debris and the potential for changes in the chemistry and dynamics of the Earth's atmosphere with implications for climate change and stratospheric ozone depletion.

Results of the UN group's activities?

“A multifaceted, interdisciplinary approach is needed to better understand the risks and impacts, and how to balance them with the essential everyday services and benefits that space activities bring to humanity,” the document says.