Ruth CleggHealth and Wellness Reporter

Alami

AlamiIt is the body's superhighway that carries information from the brain to the major organs. You may not even realize it exists, let alone that you might have to train it.

But a quick scroll through my social media feeds reveals a whole host of advice about the vagus nerve—how to heal it, stimulate it, and even reset it—all apparently to reduce stress and anxiety.

Poking your ear with something like a rubber toothbrush, moving your eyes from side to side, tapping your body, or gargling with water while wearing a weighted vest are just some of the techniques recommended to train this nerve and improve your well-being.

With our Stress levels are through the roof and burnout is on the rise among people under 35.no wonder many social media posts have gone viral and received millions of views.

Some of these methods may seem a little absurd. But is it really possible to train your powerful inner messenger, and can it really provide quick relief from life's stresses?

@love.connection

@love.connectionI decided to find out by walking into a small candlelit studio in Stockport city center where I found myself in a small group humming loudly.

I was told that humming can help stimulate the vagus nerve and slow down your heart rate. And I'm starting to feel a little calmer. I feel a low hum vibrating through my body and my brain seems a little less busy.

In this somatics class, yoga therapist Éireann Collinge guides us through a gentle movement session that combines deep breathing, rocking and swaying.

While she doesn't use all the techniques on social media, Eirian says some parts of her practice involve breath work, eye movements and tapping.

But, she said, “it’s a process,” and there’s no quick fix. It is rooted in theory that suggests we can calm our nervous system by connecting with our body.

Some scientists say this is an oversimplification of our complex internal systems. But others say it can be effective helping us find a piece of calm in a busy, stressful world.

Sarah, who lies just a few mats away from me, started coming to this class about a year ago. She says the practice has changed her life.

“I actually cried after the first session,” she says. “It felt like my brain had shut down for the first time.”

The 35-year-old, who is struggling with her mental health, says she feels like she's “scrubbing her brain with a floss”.

Xander

XanderSarah's partner, Xander, agrees. This allowed him to become more aware of his feelings.

“As men,” he explains, “we're not really programmed to do this.

“I've struggled with depression most of my adult life, but now, instead of trying to fix my thoughts, I can come to terms with my emotions and accept them.

“If I feel uneasy about something, I can take a little break from work. Go for a run, go to the mountains, for example.”

“Understanding my nervous system is a huge part of it.”

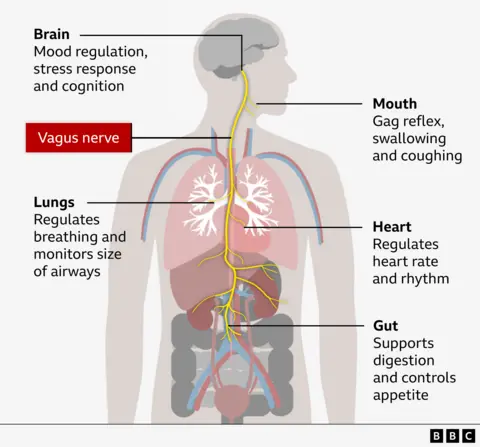

The vagus nerve (Latin for “vagus”) begins in the brain as two main branches – left and right – that connect to all major organs, constantly transmitting vital information back and forth.

It's part of the autonomic nervous system, which controls things we don't think about, such as breathing, heart rate and digestion.

The system, in particular, consists of:

- the sympathetic nervous system, which triggers the “fight or flight” principle, preparing us for everything from being chased by a wild animal to an important job interview, and

- the parasympathetic nervous system, which relies on the vagus nerve to help apply the brakes and return the body to a state of calm.

If one of them is out of sync, we start to see problems. But can we really restore balance on our own by trying to activate the vagus nerve?

Consultant psychiatrist Professor Hamish McAllister-Williams is sceptical.

“We have compelling evidence that vagus nerve stimulation can help with neurological disorders such as epilepsy and mental illnesses such as treatment-resistant depression“,” he says, “but it comes from a device built into the body – a bit like a pacemaker – that sends pulses of electrical energy to the vagus nerve.”

This device sends mild electrical impulses through the vagus nerve to the brain, causing the release of chemicals such as serotonin and dopamine, which help us regulate our mood.

Although stimulating the vagus nerve inside the body requires invasive surgery and is available to a small group of NHS patients, there is now a growing market for wearable – non-invasive – technology.

These devices, which range in price from £200 to over £1,000, are usually attached to the ear, worn around the neck or placed on the chest.

@lucylambertco

@lucylambertco“There are some credible studies that suggest that these external stimulants could potentially influence brain activity,” explains Professor McAllister-Williams. “But the evidence is much weaker than for internal devices.”

When using external devices, electrical impulses must travel through skin, tissue, muscle and fat, so it is not as simple and direct as a stimulator in the body.

Lucy Lambert says non-invasive vagus nerve stimulators like these helped her after experiencing burnout.

The mother of three quit her job as a primary school teacher because she was so “stressed, tired and anxious”.

“I was running on empty for so long – I didn’t even realize it,” says Lucy. “And then it came. The to-do list in life has become too long.

“The mental load was so enormous that I couldn’t get out of bed.”

After exhausting various medical routes and feeling like she wasn't getting anywhere, Lisa's brother recommended one of these vibrating devices that claim it sends low-level electrical impulses to the vagus nerve, often through the skin in the neck or ear.

“I noticed that when I start to feel depressed, I first get a headache.

“Then I wore the device for 10 minutes twice a day; the headache went away and my whole body calmed down.

“The vibrations actually do something.”

She says the devices didn't help her burnout, but they did help her create “the conditions where real healing can happen.”

@lucylambertco

@lucylambertcoDr. Chris Barker, who specializes in pain management, says the field of medicine is still evolving.

He says there is a growing understanding of the importance of the vagus nerve, but while there is “clear evidence” of the impact of an imbalanced nervous system on everything from our mental health to our heart rate and our ability to digest food, that doesn't mean we have all the answers (yet) to how to fix the problems.

“It's really smart to focus on something that's problematic and try to fix it.

“Our bodies are of course very complex, and sometimes the problem we see may be part of an imbalance in the wider system.”

According to him, it is not a matter of extremes. It's “about figuring out what works for you” and that can often take time.

It's worth noting that if you have heart or respiratory conditions, you should seek medical attention before attempting to restore balance or stimulate the nervous system.

Now, several years after experiencing burnout, Lucy, 47, is opening her own business, helping others gain emotional stability and confidence.

She still uses her devices daily, meditates, and regularly checks in to see how she's feeling. “Devices force me to relax and switch off.”

But she agrees it's hard to know whether the devices matter or the fact that she's taking a much-needed time out.

These devices lack reliable scientific evidence, but for Lucy they played an important role in her recovery. She says understanding her nervous system and the importance of the vagus nerve has given her strength.

“It has helped me take responsibility for my mental health and wellbeing, which is very important.”