James GallagherHealth and Science Correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe flu should always be taken seriously. It's a virus that kills thousands of people every winter and puts significant strain on hospitals.

However, I can't remember a flu season that went this way. There have been claims in the media and even in NHS England that it is both a “superflu” and “unprecedented”, while experts say this year's flu is not unusual and are being accused of a “crying wolf”.

So what's really going on and has anything really changed this year?

As I reported in early Novemberthere were fears that the flu season could be the worst in a decade.

Scientists tracking a variety of flu viruses around the world noticed that in June, a strain of flu (a type called H3N2) had seven new mutations.

This newly mutated virus quickly became the dominant form of H3N2 and was named subclade-K.

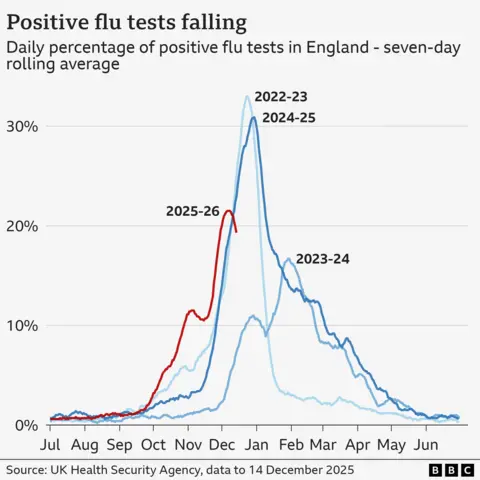

The UK's flu season started a month early, hinting that the virus may be spreading more widely than usual, and it was too late to adjust this year's flu vaccine to match the new mutations.

This was a concern, but the reality is more consistent with a regular flu than a superflu.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe K-influenza virus has not acquired significant ability to spread throughout the population.

“It was basically spreading at the same rate as previous years, it was closer to the upper limit, but it was not an outlier,” says Professor Christophe Fraser, who analyzes the spread of the virus at the University of Oxford's Institute of Pandemic Sciences.

His team's latest analyses, which have not yet been published, show that the mutations did give the virus a slight advantage in overcoming our immunity – about 5-10% more than usual. It is unclear whether this applies to everyone or only affects children and young people, who were less likely to get the flu in the past and who are still hit hardest.

H3N2 viruses always tend to be more severe in older people, and there is no clear evidence that this year's virus is deadlier than expected. A rapid analysis of the seasonal flu vaccine also showed that it is effective. in line with previous years despite concerns about inconsistency.

Dr Jamie Lopez Bernal, UKHSA consultant epidemiologist, said: “What we've seen that's unusual about this season is the early start to the season, we've also seen this change in the virus, with more evolution than we usually see.

“But overall, in terms of the impact on the NHS and the impact on people's health, we are looking at an overall typical flu season.”

There is speculation that the flu may have already peaked, although this is subject to significant uncertainty. Questions have been raised about what happens at Christmas, when everyone gets together and the virus can more easily infect older people, who are at greater risk. There are also signs that another flu strain, H1N1, is spreading in Europe, which could lead to more cases here too.

But “typical flu season” is probably not the feeling you get when watching or reading the news.

Statistical art has been used to compare the early flu season with a season that began much later, allowing it to be argued that flu cases “incredibly 10 times higher” than in 2023.

Technically this was true, but it's like saying the train to Glasgow got you there in record time… but the journey times were identical, you just booked an earlier train.

NHS England was not the first organization to start calling the disease a “super flu”, but Professor Meghana Pandit, National Medical Director of NHS England, called it a “super flu”.unprecedented wave of superflu“.

The British Medical Association suggested that influenza was being used to stoke panic while local doctors decided whether to continue the strike.

“Super flu” is not a scientific description and the BBC medical team did not find any experts who believed the description to be accurate.

“I don't think it's a useful term, there's no particularly unusual set of symptoms, there's no indication that it's associated with exceptional severity, exceptional spread or exceptional health impact,” Professor Fraser says.

One of Britain's leading flu scientists, Professor Nicola Lewis, director of the World Influenza Center at the Francis Crick Institute, said the virus “is not particularly unusual” and that she saw “no evidence that the virus is “particularly different” and superflu “doesn't fit my description.”

Former deputy chief medical officer for England during the pandemic, Professor Jonathan Van-Tam published: “I’m very unclear what is meant by the rather silly term “superflu.”

Crying wolf?

Persuading people to get the flu vaccine saves lives, and an estimated 100,000 people were affected by the flu shot last winter. from the hospital.

However, experts have begun to wonder whether the escalation of language used in the wake of the Covid pandemic could undermine confidence in official health advice. Previous winters have seen warnings of a triple epidemic of influenza, Covid and RSV; then it was upgraded to quademic addition of norovirus; This year it's a super flu.

Dr Simon Williams, who researches psychology and public health at Swansea University, says there are problems with “the current narrative that every winter is more or less 'the worst'” and risks causing a “cry wolf” effect that undermines trust and means people become “desensitized” to advice.

He said there was a danger of “over-indulging in the narrative that viruses will overwhelm the NHS”, although “ultimately the NHS will not be overwhelmed to the point that it cannot carry out emergency and essential functions”.

Instead, he argues that there needs to be a “delicate balance” between raising awareness and “not falling into the trap of spreading fear messages or being overly alarmist, which can backfire.”

Professor Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham, agrees: “I think using words like superflu raises concerns that we could one day be faced with a real superflu.

“We have to be very, very careful in how we communicate these things to the public because there is a risk that we might cry wolf.”