Ino time echo chambers and hyper-personalization, where algorithms narrow the focus of what we see online. The Walrus focuses on journalism that pushes the envelope and tells you what you didn't know you need to know. Here are nine stories from 2025, chosen by our editors, that opened up new worlds and ideas for our team and our readers.

Karin Abuseif, Senior Editor: As an editor, my ears always perk up when I hear a story that's called “juicy.” This is how we talked about writer's contribution Taja Aisenessay, “The publishing industry faces a gambling problem” as she went through our editorial process. Taja interviewed writers, book editors and literary agents about the concept of the “sales track,” a term for the number of books a writer has sold. Low sales numbers can shorten a writer's career before it even really begins, determining how an agent markets their second book and whether editors will buy it. It was juicy because Taja was able to get votes, including an editor at a Big Five publishing house. But I also liked the way it lifts the lid on an industry I know little about, but whose products I consume. If I read a book by a debut author and never see a second book, I wonder what happened to them. The article answers this question: They probably didn't get a second chance. As an editor – of journalism, not of books – I've seen firsthand how writers find their voice: with one article, then another, then another. It would be a shame if they didn't get the chance.

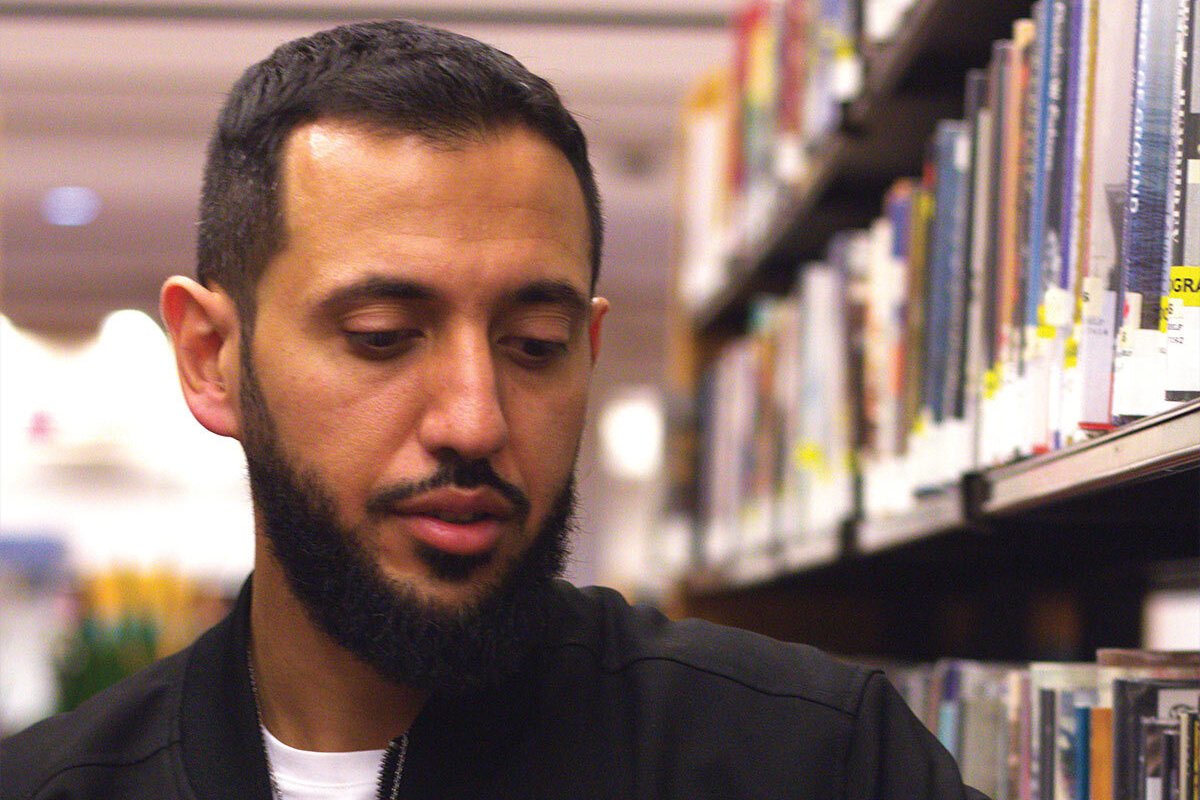

Carmine Starnino, editor-in-chief: It is rare to find a magazine story in which the writer explores her own motives as carefully as those of her hero. After all, reporting is based on a presumption of ethical clarity, with the journalist serving as a moral arbiter. Michelle Shefard turns this convention inside out. She is, of course, a former national security reporter who headed Toronto Star coverage of the Toronto 18, a group of eighteen Muslim men and youth arrested in 2006 for plotting a terrorist attack. After years of ordeal, twenty-four-year-old leader Zakaria Amara was sentenced to life imprisonment. His parole in 2022 has prompted Shepard to question how he became radicalized, why he resorted to violence and whether he has truly been rehabilitated. IN “How a future terrorist changed his life“, she returns to the case she helped bring to national prominence, examining not only Amara's transformation but also her own complicity in shaping the media portrait that defined him. The result is a remarkable act of journalistic introspection: a story that reveals the complex power dynamics between storyteller and subject and reveals how those who report on extremism influence the terms of public forgiveness. Shepard Shepard's work in empathetic storytelling belongs in every journalism class.

Samia Madwar, Senior Editor: At the moment I know at least four people who have been persecuted. Two of them were women whose partners at the time followed them whenever the women made plans without them, claiming they did it out of love or protection. Two of them were university students, studying at different schools, and each was pursued by a classmate who wanted to date them. I never made any connections between these cases because they all happened at different times. I've never wondered what makes a stalker so obsessively pursue a target, or why they so often confuse stalking with romance. But Sheima Benembarek did it. When she asked me to write pursuit function (legally known as criminal prosecution), I immediately wanted to know more. For over a year, she interviewed stalking victims and experts, piecing together harrowing anecdotes with an informed perspective on where stalking behavior comes from, why we need to take it more seriously, and why it will take a concerted effort by society—that is, all of us—to stop it.

Claire Cooper, Editor-in-Chief: I've reached that stage in life where an evening meeting with friends inevitably includes updates on the health of everyone's aging parents. This topic can easily turn a busy night into a gloomy one, so one particular moment from Arno Kopecky's beautiful memoirs I really remember his father. In talking about his father's peak years as a scientist in contrast to his current battle with dementia, Arnault reminds himself—and me—that even if these final years are characterized by decline, they are not a total loss. And it doesn't take away from what someone has accomplished in their life: “People lose children, lovers, brothers and sisters. These are tragedies. It's a cause for celebration, in a strange way: my father lived a long life, had a successful career. He saw his two sons grow up… I should have a father who loves me.”

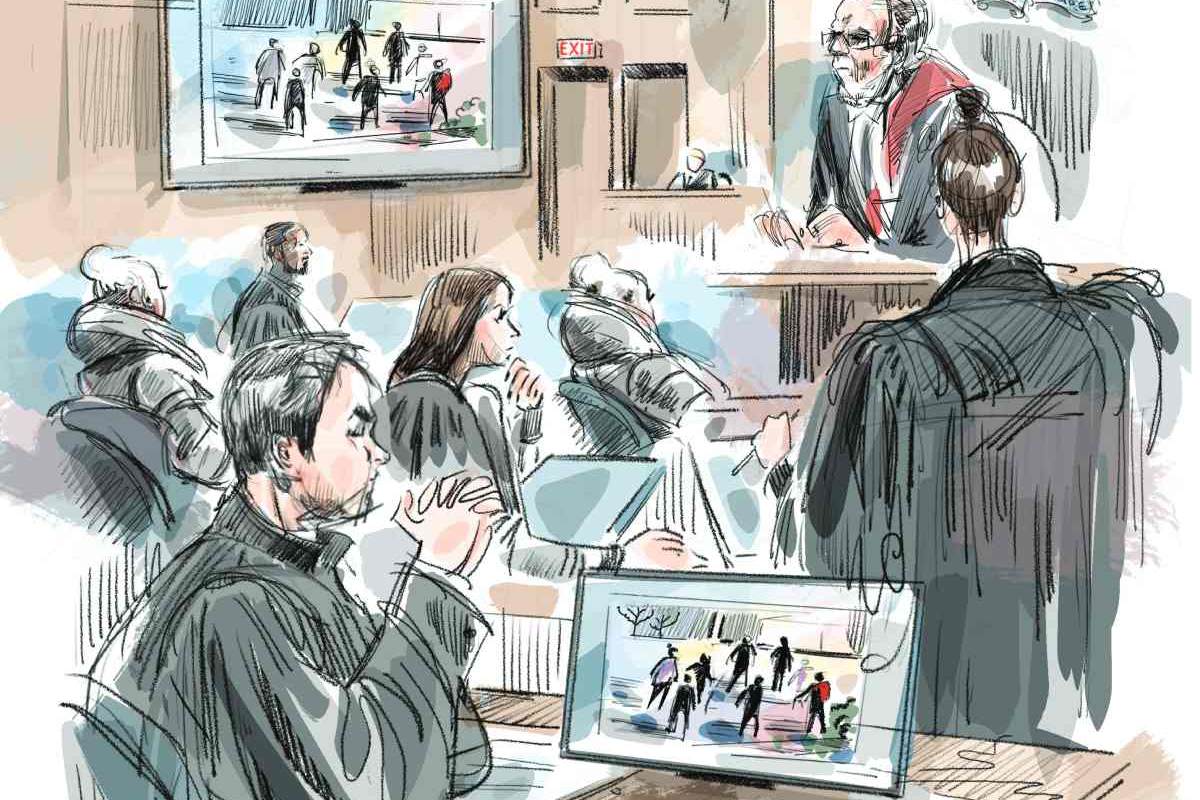

Daphne Isenberg, Features Editor: I spent much of the 2022 winter break thinking about the recent death of a man named Kenneth Lee. He was killed in downtown Toronto after he was attacked by eight teenage girls who faced criminal charges. Children, I kept thinking. Why did they attack him? Where did their anger come from? And what did this tell us about society, education, raising children? Journalist from Toronto Inori Roy I decided to answer these questions. From April 2024 to May this year, Roy attended the girls' trial, carefully piecing together the events of the night of Lee's death. She spoke to experts in child development and mental health. She carefully recorded her own observations of how the girls behaved in court, whether they were remorseful or not, as she hoped. Her reports are reliable and her conclusions are reasonable. Her sensibility is quiet and refined. Her description of Lee's final moments as he sat on the ground clutching the edge of the coat of the woman who tried to save his life breaks my heart all over again.

Harley Rustad, senior editor: The first building my dad built when he built our house was a small sauna. He is sitting in the forest; heated by an antique cast iron wood stove; its interior is lined with fragrant cedar planks. It's the most relaxing way to spend half an hour with the sound of a crackling fire and the patter of winter rain outside. It's serene here. I recently learned that sauna lovers all over the world are turning this quiet, subdued pastime into a cacophonous performance of shocking levels. Login as writer Sarah Everts made, steamy, sweaty, freaky arena World Sauna Championshipan international competition held this year in Italy, in which competitors (often professionals working in spas) twirl towels, blow fragrant steam and prance around a sweaty audience, but do so with complicated procedures. Think historical novelizations or pop culture dramatizations. Trust me: it's weird. The countries of the northern hemisphere send their best specialists, with the exception of Finland, which, due to an arrogant superiority complex, boycotts all this, and this fact seemed funny to me.

Ariella Garmez, Deputy Editor: In the vast canon of poetry and literature written about our fear of death, you are unlikely to see the words “terremation” (that is, “covering the body with organic wood chips and alfalfa”) or “aquamation” (think of a very hot hot tub). Fortunately, Ellen Himelfarb stepped in to fill the void. Her essay about creative approaches to the costly problem of the human corpse surprised me not only with its macabre subject matter, but also with how lyrically it describes such ungodly terms. Concepts like “human composting” and “QR codes for burial sites” may strike you askance, as can her tireless wit in the face of the inevitable: “I’m intrigued by the possibility of creative control,” she writes of her husband’s changing burial plans. “It's also comforting to think that this may be the last time I have the upper hand in my marriage.”

Siddhesh Inamdar, Features Editor: The story begins with an anecdote about writers Anam Zakaria and Haroon Khalid driving home in an Uber from a doctor's appointment for their young daughter, frustrated that they continue to seek an ENT specialist despite a months-long wait. As they strike up a conversation with the Uber driver, they discover that he is a recent immigrant from Afghanistan with years of experience working at a military hospital in Kabul as – yes, you guessed it – an ENT specialist. This state of affairs, where qualified specialists work part-time, even despite the shortage of the very sectors in which they have the opportunity to practice, is surprising only because it is right. The finding that Zakaria and Khalid note in their article, that the Canadian economy could add up to $50 billion to annual GDP by bringing immigrants to the same employment levels as those born here, makes this doubly beneficial. The fact, of course, remains that there has hardly ever been a more difficult time to be an immigrant in Canada, with the government flattening the country's population growth, regardless of its impact on the economy – at a time when it is already suffering from the trade war with the US. This is the most mysterious part of not only this story, but also the ongoing grim reality. (“We have plenty of space to share, and we are hospitable in our own awkward and unsettling way,” Charles Foran writes in V.hat “I want the animals in my house to know”“, a poetic story that I couldn't help but include here – about how he shared his home with creatures who also call it their home – as an allegorical reminder of Canada.)

Monika Varzecha, digital editor: I spend so much of my life online that I've started to follow stories that actually go somewhere, that pay attention to geography and physical space. Andrew Seale registered for Snowbirds of Quebec at motels and hotels in Hollywood and Hallandale Beach, Florida (complete with a side quest at Big Daddy's Pub). This community was not on my radar at all as someone from Ontario who barely graduated from high school with a French degree. And this story turned out to be not just a fun trip to the south, but also a reflection on identity, change and home.