For more than a decade, The Metals Company has poured millions of dollars into researching and developing technology for mining seafloors at extreme depths, funding scientific studies to evaluate the environmental impact, and persuading investors and political leaders to support their vision of scraping minerals like cobalt and copper from the ocean floor.

In 2021, the company went public, opening at $11.05 per share. Then their stock plummeted as global regulators debated what rules to impose on sea bed mining hitting $0.55 a share at its lowest point. Last week, the company’s stock was back up to $7.89, a tenfold increase over a single year despite large, continual losses and no ability to profit from selling minerals until at least late 2027 due to pending permits.

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

“We see a path for this stock to continue to perform very well,” said Craig Shesky, the company’s chief financial officer, to investors at a virtual conference this month. “We are sitting really in the eye of the storm when it comes to what the U.S. needs to do to diversify supply chains for these metals away from China.”

The dramatic rise reflects how the still-unprofitable seabed mining industry catapulted forward in 2025, driven by President Donald Trump’s eagerness to cement American dominance of critical minerals, his disregard for international norms, and his willingness to override the concerns of scientists and Indigenous Pacific peoples alike.

Manganese, cobalt, copper and nickel are among what the U.S. calls “critical minerals” necessary to create batteries for consumer goods like cell phones and electric cars, and military technologies like missiles, fighter jets and tanks. The U.S. currently gets most of its critical minerals from China, something Trump is eager to change. Industry players argue that mining the seafloor is necessary to help the world transition away from its reliance on fossil fuels to combat climate change, but scientists say that we know too little about the potential environmental damage from mining, and that disturbing the sea floor might release more carbon into the atmosphere.

Trump’s approach to deep-sea mining has been characterized by an aggressive pursuit of his goals with little regard for international law. In April, he prompted global outrage by asserting that the U.S. has the right to mine in international waters, ignoring an ongoing United Nations process to regulate deep sea mining on the high seas through the International Seabed Authority, or ISA. Prior to Trump’s move, Indigenous environmental advocates from Hawaiʻi, French Polynesia and the Cook Islands spent years advocating at the ISA to assert their rights and the cultural importance of the ocean to their peoples. They have been making progress in shaping the proposed regulations, but now Trump’s “America First” approach is undermining years of negotiations.

Anita Hofschneider / Grist

“As navigators of Oceania, we are often met with adverse conditions,” said Solomon Kahoʻohalahala, a Native Hawaiian advocate from the island of Lānaʻi. “The conditions that are presented to us may be adverse, but we understand how to navigate through them, around them, and redirect our sails.”

Currently, the international waters that Trump and The Metals Company are eyeing make up more than 36 million acres in a region known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone south of Hawaiʻi that is known for its rich deposits of cobalt and other minerals. Trump is also considering mining in the national waters of the Cook Islands, across 35.5 million acres near the Marianas Trench and across 33 million acres off of American Samoa. All told, the administration is evaluating the potential for mining exploration or commercialization across more than 104.5 million acres, a combined area comparable to the entire state of California.

“The deeper you go in the ocean, the less life you find,” Shesky told investors. “It’s more like picking up golf balls at a driving range than traditional land-based mining.

Most life forms at depths where mining is being considered haven’t been named, much less studied, but scientists have been racing to research the effects of deep-sea mining ahead of any commercialization. In March, researchers in the United Kingdom found that more than four decades after a seabed mining expedition in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, the site still hadn’t fully recovered.

William West / AFP via Getty Images

In November, scientists in Hawaiʻi found that sediment released by a mining test weakened the ocean food web by prompting plankton to ingest less nutritious particles, and in December, another study found that two years after a seabed had been scraped for minerals, the number of sea creatures on the ocean’s floor such as worms and molluscs had fallen 37 percent. The Metals Company funded much of the research but has pushed back on the findings.

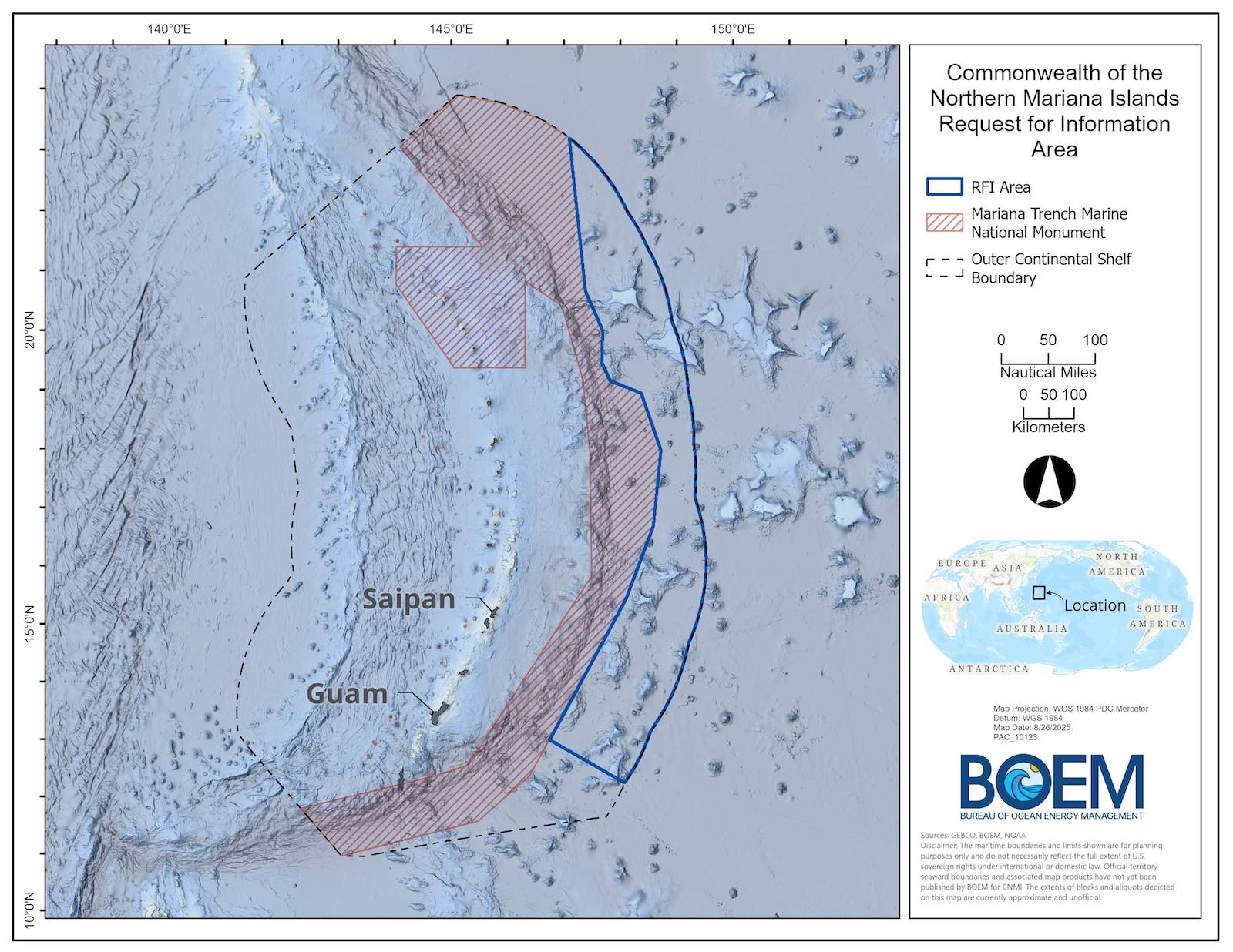

The industry’s downplaying of environmental risks is frustrating to Sheila Babauta, who is an Indigenous Chamorro-Pohnpeian resident of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, or CNMI. Her home archipelago in the western Pacific is the latest place that Trump has targeted for mining, and commercial mining activities would carve a banana-shaped region east of the archipelago that spans the entire length of the island chain bordering the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument which was established for its unique biodiversity. The project area is more than 35 million acres, larger than the entire state of Florida.

“I refuse to accept that the waters around us belong to the U.S.,” she said. “It is the Indigenous peoples of this land, of Micronesia, that have the historic connection and roots to this part of the world, to the proposed area of deep-sea mining, and 50 years of a colonial relationship does not justify the extraction and the destruction that is being proposed.”

Ian Forsyth/Getty Images

Babauta chairs the board of a community group, Friends of the Marianas Trench, which supports protecting that marine monument. She and other residents of the CNMI were surprised by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s November announcement that companies have been invited to consider leasing parts of their ocean.

Now Babauta is scrambling to help her neighbors make sense of what’s at stake and how to give meaningful input while juggling holiday and family obligations.

“From the very beginning the process was colonial,” she said. “Our political leadership was not consulted before the (proposal) was issued. This industry and this proposition is being imposed on us — it’s not something that came from us.”

On the same day in December that The Metals Company was pitching investors, Babauta and her neighbors were reeling from a decision by the Trump administration to limit how much time they have to respond to mining proposals. The highest-ranking political officials in the commonwealth and the neighboring island of Guam — two governors and two Congress members — asked Trump to extend the public comment period another 120 days to allow their residents time to educate themselves on the industry before responding. Instead, the Trump administration approved a 30-day extension for public comments reflecting a pattern by the administration to limit public input and fast-track new extraction projects.

Babauta said many residents she spoke to were unaware of Trump’s proposal and unfamiliar with deep-sea mining. “There was no collaboration and there was no meaningful engagement. And now we are forced to participate in a process that is not our own. They decide what a comment should look like, what is substantive; they decide when the comment period should begin and end.”

“The process is not meant for us to be heard,” she continued. “It’s not created for that. It’s definitely a formality and a facade.”

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

Underpinning her disillusionment is the knowledge of what’s happening in American Samoa, where the territory’s political leaders unilaterally opposed a deep-sea mining proposal across 18 million acers of their waters, citing Samoan cultural beliefs rooted in the ocean and the fact that tuna makes up 99.5 percent of their exports. The Trump administration responded by nearly doubling the size of the region for potential mining claims and moving forward with the mining permitting process.

Blue Ocean Law, a Guam-based law firm founded by Julian Aguon, has been pointing to the industry’s potential risks to Indigenous food systems, spiritual beliefs, traditional navigation corridors, and more.

“Because these cultural practices cannot be relocated, replicated, or compensated through mitigation, the resulting injuries would be irreversible and would fall overwhelmingly on Indigenous peoples who already bear the ongoing burdens of militarization, environmental degradation, and political disenfranchisement in the Marianas,” the firm said in testimony submitted to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM.

The CNMI government, which recently cut workers’ hours to save money amidst a long-running tourism downturn, has been scrambling to schedule a Dec. 23 public hearing to help educate the community on how to submit comments — all the while questioning whether decision-makers thousands of miles away will listen. “We posed that question to BOEM, I said, ‘How much weight will BOEM give to comments like, ‘This ocean feeds us. It’s our culture. We travel on it, and this is where we survive’?” said Henry Hofschneider, chief of staff to CNMI Gov. David Apatang, during a press conference last week. “They can’t answer that question.”

The Metals Company is far from the only corporation hoping to mine the seafloor. The industry is growing, and attracting new players hoping to cash in on Trump’s dogged support. One company is Impossible Metals, a five-year-old seabed mining startup that’s vying to mine in the Marianas and American Samoa, that argues their robot technology won’t have a long-lasting, material impact on the environment. “If it shows through the environmental impact statement that we are wrong, we won’t go mining,” promised its chief executive officer, Oliver Gunasekara.

John Wong / AFP via Getty Images

Gunasekara doesn’t share Sheila Babauta’s concerns about the need for more time for CNMI residents to weigh in on the mining proposal. “I think 60 days should be sufficient. You’re talking about writing a document, giving input,” he said. “The administration has declared a national emergency given how much of these minerals are controlled by China and I think unfortunately this is a strategy used by NGOs to try and delay, and so the question is, is 60 days enough time for people to document their views? I think it is.”

He’s similarly undeterred by Aguon’s comments about cultural risks. “People have a spiritual connection to the ocean, and we have to respect their beliefs, but also understand that the world needs these metals,” he said. “My understanding is that the intangible cultural connections have died down because most of the specific communities are Christian, and so these are beliefs that really predate Christian activities, and so as the communities there adopted Christianity, some of the historic spiritual connections have diminished.”

Unlike The Metals Company, Gunasekara wants to offer a 1 percent profit share to the territories, and thinks that Congress should change federal law to allow territories to receive revenue from deep-sea mining. But there is no requirement that companies share their profits, and any decision to allow revenue sharing would belong to a Congress in which the territories have no vote.

And while anyone on the U.S. continent can download an investing app like Robinhood and buy shares of a mineral mining company to try to cash in on the industry, territory residents are mostly shut out from that too — incomes in the CNMI and American Samoa are less than half of the national median, and U.S. brokerages like Robinhood and Vanguard often don’t even allow territorial residents to open up investment accounts because they lack home mail delivery addresses.

“In effect, the proposed framework replicates patterns historically associated with resource colonialism, where extraction proceeds under federal authority, profits flow outward, and Indigenous peoples and local communities are left with permanent ecological damage and no economic return,” Blue Ocean Law testified. “Without substantive benefit-sharing, consent procedures, or local control, deep-sea mining would deepen existing inequalities and belie contemporary standards of environmental justice and Indigenous rights.”

Such concerns were not raised at the December virtual investor conference, where the focus was on growth potentials. “Throughout history, from oil to semiconductors, the early leaders in every major industrial transformation have delivered extraordinary returns to those who recognize the shift early,” said a top official from the firm hosting the conference.

“This is a rare inflection point.”