A central goal of human genetics is to learn how genetic variants impact the cellular and molecular phenotypes that underpin human diseases. Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) are commonly used to study genetic lesions associated with diseases such as cancer because of extensive genetic homology with humans and physiological relevance1,2,3,4. Genome-editing technologies are also being increasingly used in GEMMs to accelerate the understanding of human diseases5,6,7,8.

Species-specific genetic inconsistencies complicate the development and benchmarking of GEMMs for studying human genetic variation and interpreting biological effects9. The complex nonlinear mapping of gene orthologs can make it difficult to find orthologous loci that can be engineered in mice. The effects of altering orthologous sequences may also vary depending on the local sequence context. Variants at conserved sites may also have different roles in humans and mice because of interspecies differences.

Existing genetic resources and computational tools can help but there remains a need for integrative platforms that provide comprehensive dictionaries of cross-species genetic variants to engineer and study mutations with identical sequence and/or functional changes. Systematic analyses of orthologous mouse variants with genome editing would be facilitated by automated, user-friendly prediction tools that avoid the need for error-prone manual searching across different resources. Results should also be standardized to enable downstream analyses such as guide RNA design and functional prediction of pathogenic effects.

We developed H2M (human-to-mouse; https://github.com/kexindon/h2m-public), a computational pipeline that processes human genetic variation data to model and predict the consequences of equivalent mouse variants and to help devise precision engineering strategies to introduce corresponding mutations in mice. H2M uses genetic variant data as input to systematically identify, model and visualize orthologous variants across thousands of mutations. While we showcase its utility for human-to-mouse and mouse-to-human analyses here, H2M is compatible with any organism with a sequenced reference genome.

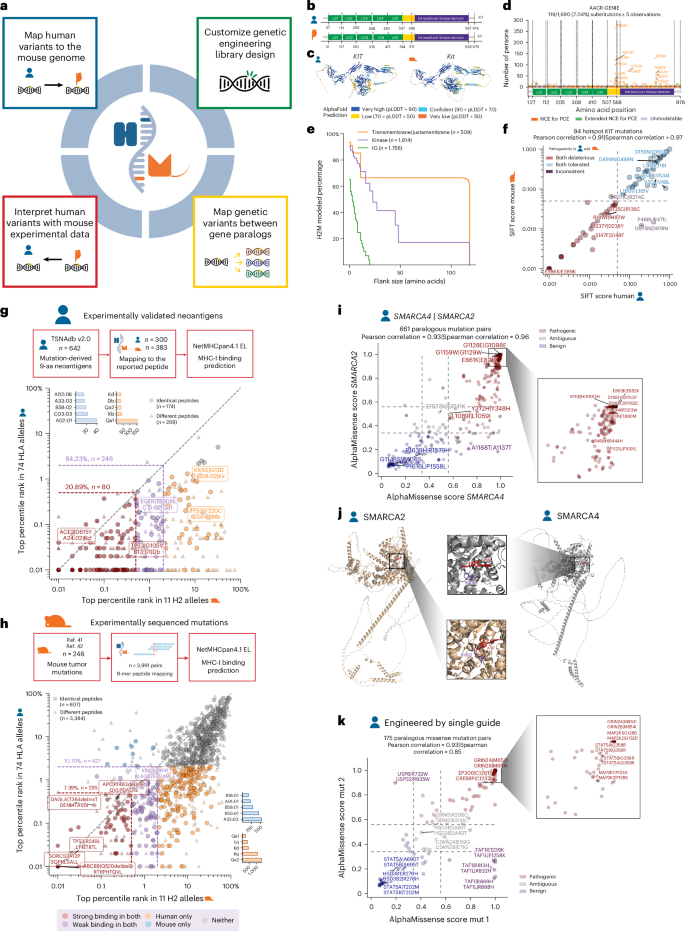

H2M performs four main steps: (1) queries orthologous genes; (2) aligns wild-type transcripts or peptides; (3) simulates mutations; and (4) checks and models functional effects (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1). It uses a built-in catalog of mouse and human homologs10,11,12,13 (Supplementary Table 1) to identify gene pairs of interest and then retrieves complete sequences and all transcript versions for each gene.

a, H2M performs four main steps: (1) queries orthologous genes, (2) aligns wild-type transcripts or peptides, (3) simulates mutations, and (4) checks and models functional effects. b, H2M uses three modeling strategies depending on the specific sequence change effect of the input. For noncoding and frame-shifting mutations, H2M uses (I) NCE-only to model the same DNA-level alteration. For amino acid substitutions and indels, H2M uses either (II) NCE-for-PCE if the DNA mutation leads to the same amino acid change in both genomes or (III) extended NCE-for-PCE if a different DNA mutation is needed to model the target amino acid change. c, Schematic of the flank sequence for the mutation site. Flank size is defined as the combined length of consensus nucleotides (for noncoding variants) or peptides (for coding variants) on both sides of the mutated site. d, Schematic of H2M database generation. M, million; muts, mutations. e, Pie chart visualizing the presence of mouse gene orthologs for human genes in the input human dataset. f, Percentages of human mutations in the H2M database that can be modeled in the mouse genome, stratified by the data source. g, Distribution of flank sizes for all the human variants in H2M database, split by NCE (left) for noncoding mutations and PCE (right) for coding mutations. h, Number of mutations that are prime-editing and base-editing amenable in the selected subset of the H2M database. NCE, nucleotide change effect; PCE, peptide change effect.

For each transcript, H2M locates exons and introns, simulates RNA splicing and obtains complete transcript sequences. It then simulates, checks and models the functional effects of target gene mutations at both nucleotide and peptide levels. To determine whether mutations map to locally conserved regions, H2M aligns wild-type transcripts (for noncoding mutations) or peptide sequences (for coding mutations) using the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm. If the human mutation has a corresponding site in the mouse genome, H2M uses three modeling strategies (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Table 1).

For all entries, H2M computes the same nucleotide change in the mouse transcript and outputs the equivalent NCE (nucleotide change effect), defined as the DNA-level modification induced by a mutation (strategy I: NCE-only modeling; Extended Data Fig. 2a–c). Because the same nucleotide alteration at corresponding human and mouse loci will not always result in the same amino acid, H2M also computes the effects of sequence changes at the protein level (peptide change effect, PCE) for coding variants (that is, amino acid change). To account for these potential differences, H2M also generates DNA-level changes that should produce the same protein-coding effect in both species. After simulating the same NCE in both genes and comparing the resulting amino acid alterations, H2M keeps the variant equivalent that mirrors both the NCE and the PCE (strategy II: NCE-for-PCE modeling; Extended Data Fig. 2d). Otherwise, H2M tries to provide extended PCE equivalents with different NCEs on the basis of codon redundancy (strategy III: extended NCE-for-PCE modeling; Extended Data Fig. 2e).

The output of H2M includes a wealth of standardized information that can be used for many different types of downstream analyses (Extended Data Table 2). In addition to mutation coordinates and DNA-level sequence alterations in MAF format, H2M provides transcript-level and protein-level sequence change effects using standard HGVS nomenclature14.

Genome sequencing studies have cataloged millions of human germline and somatic mutations. A corresponding murine catalog would be valuable to predict the effects of these mutations, devise strategies to build new GEMMs and interpret experimental data from existing models. With this in mind, we queried AACR-GENIE15, COSMIC16 and ClinVar17 to retrieve human variants involving nucleotide substitutions or small indels and used H2M to identify human–mouse gene-level orthologous relationships (Fig. 1d). We mapped 96% of input human genes to mouse orthologs, with most mappings being one-to-one (Fig. 1e). The remaining 4% lacked a mouse ortholog or homologous relationship annotation. We then used H2M to predict murine equivalents and build the H2M database (version 1), a dictionary encompassing 3,171,709 human-to-mouse mutation mappings (May 2024) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

H2M predicts that >80% of human variants can be modeled in mice (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Most of these fall under the NCE-only and NCE-for-PCE categories, which can be modeled by introducing the same nucleotide-level mutations to perform high-confidence cross-species studies. We observed a slightly lower coverage for indels compared to single-nucleotide or multinucleotide substitutions.

We found that a higher percentage of coding mutations can be modeled compared to those in noncoding regions, consistent with the higher sequence conservation in coding regions. Within noncoding regions, mutations in splice sites show a higher modeling prediction percentage than those present in deep intronic areas.

To address species-specific sequence differences surrounding a site corresponding to a variant of interest, we introduced a flexible parameter called ‘flank size’, defined as the combined length of consensus nucleotides (for noncoding variants) or amino acids (for coding variants) on either side of the mutated site (Fig. 1c). In the H2M database, 50% of coding mutations have a flank size of 18 or fewer amino acids and 50% of noncoding mutations have a flank size of 14 or fewer nucleotides (Fig. 1g). The percentage of variants that can be modeled according to H2M decreases as the flank size expands, as it restricts engineerable mutations to regions with higher sequence homology (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

Base-editing and prime-editing technologies enable researchers to precisely and efficiently engineer and study mutations of interest within their native genetic environments18. Comparative studies remain challenging in part because of the lack of computational tools for fast and accurate identification and design of editing strategies that faithfully mirror cross-species genetic changes. To address this gap, we used H2M to select 4,944 cancer-associated human–mouse mutation pairs followed by PEGG (prime-editing guide generator) to design gRNAs for base and prime editing19 (Fig. 1d). This allowed us to build a database of 24,680 base-editing gRNAs for 4,612 mutations (2,720 human and 1,892 mouse) and 48,255 prime-editing gRNAs for 9,651 mutations (4,944 human and 4,707 mouse) (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). We also designed NGN protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) gRNAs and annotated NCN cytosine base-editing gRNAs to ensure compatibility with NCN-context-dependent cytosine base editors20 and PAM-flexible variants such as SpCas9-NG (ref. 21).

To ensure free and easy access to this database, we built an online portal (https://human2mouse.com/) that provides user-friendly browsing, visualization and data downloads. Overall, the H2M database represents a comprehensive and reliable source for modeling human variants of interest in the mouse genome. We expect to periodically update and expand the H2M database as more human genome sequencing data are collated and analyzed.

H2M can also perform reverse mouse-to-human mapping and various types of functional interspecies modeling on the basis of sequence change effects (Fig. 2a). We provide three case studies below that broadly illustrate this point and serve as general templates for practical implementation of H2M.

a, Representative applications of H2M. b, Functional domains of KIT (Kit in mouse) labeled according to UniProt (P10721 in human, P05532 in mouse). LG, Ig-like domain; yellow, transmembrane/juxtamembrane domain; orange, SH2-binding domain. c, AlphaFold-predicted structures of human (AF-P10721-F1-v4) and mouse (AF-P05532-F1-v4) KIT protein. pLDDT, predicted local distance difference test. d, Scatter plot of frequencies of KIT missense mutations in persons with cancer according to AACR-GENIE, colored by H2M modeling. A red dashed line denotes occurrence in five persons. The H2M modeling percentage is calculated for unique amino acid substitutions. e, Kaplan–Meier curve visualizing the percentage of human KIT missense mutations that can be modeled by H2M, stratified by functional domain. f, Relationship between SIFT pathogenicity scores for human–mouse mutation pairs in KIT, log-scaled. Mutation pairs are selected according to the occurrence of human mutations in AACR-GENIE (≥5 persons). Points are labeled by amino acid substitutions in the format of ‘human | mouse’. Pathogenicity classification: deleterious, 0–0.05; tolerated, 0.05–1. Pearson correlation (two-sided test) = 0.91 (P = 5.2 × 10−38); Spearman correlation (two-sided test) = 0.97 (P = 4.3 × 10−58). g, Schematic of the generation of human–mouse immunogenic peptide pairs from mutation-derived, experiment-validated human tumor neoantigens and the relationship of MHC-I binding %Rank between them. Pearson correlation (two-sided test) = 0.12 (P = 0.02); Spearman correlation (two-sided test) = 0.43 (P = 5.7 × 10−19). The top %Rank is selected for each peptide among the predicted set of MHC-I alleles. The top five binding alleles are shown in small bar plots for human (blue) and mouse (orange). Points are colored by binding classifications in both human and mouse. Strong bindings, %Rank < 0.5%; weak bindings, %Rank < 2%. Circle, identical 9-mer peptides generated by corresponding mutation in human and mouse; triangle, different 9-mer peptides generated by corresponding mutation in human and mouse. h, Schematic of the generation of human–mouse peptide pairs from sequenced mutations of mouse tumor models and the relationship of MHC-I binding %Rank among them. Pearson correlation (two-sided test) = 0.67 (P < 1 × 10−300); Spearman correlation (two-sided test) = 0.57 (P < 1 × 10−300). The top %Rank selection, binding thresholds, colors and shapes are the same as in b. i, Relationship of AlphaMissense pathogenicity scores for human SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 mutation pairs. Points are labeled by amino acid substitutions in the format of SMARCA4 | SMARCA2. Pathogenicity classification: pathogenic, 0.56–1; ambiguous, 0.34–0.56; benign, 0.04–0.34. Pearson correlation (two-sided test) = 0.93 (P = 6.8 × 10−285); Spearman correlation (two-sided test) = 0.96 (P < 1 × 10−300). j, AlphaFold3-predicted ATP (red)-bound structures of human BRG1 (gene: SMARCA4) and BRM (gene: SMARCA2). H2M-paired residues, BRG1 R1192 and BRM R1162, are highlighted (purple). k, Relationship between AlphaMissense pathogenicity scores for human paralogous mutation pairs that can be engineered in parallel with the same base editor and one single gRNA. Points are labeled by paired genes and the amino acid substitutions. Pathogenicity classification is the same as in c. Pearson correlation (two-sided test) = 0.85 (P = 3.97 × 10−51); Spearman correlation (two-sided test) = 0.84 (P = 1.23 × 10−49).

The functional similarity of human and mouse variants depends on local sequence conservation, even for highly conserved ortholog pairs22. We reasoned that, if increased flank size similarities in a region suggest higher evolutionary conservation and functional importance, then mutations within this region may produce notable effects that are conserved across species. To illustrate this point, we investigated the human proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT) and its mouse ortholog (Kit). Both orthologs are composed of extracellular tandem immunoglobulin (Ig) domains, a transmembrane domain and an intracellular kinase domain23 (Fig. 2b,c). Cancer-associated mutations are distributed across all exons of KIT but recurrent ‘hotspot’ mutations often map to the transmembrane, juxtamembrane and kinase domains, suggesting higher functional importance (Fig. 2d). Consistent with this, H2M found a significantly higher proportion of human missense mutations within the transmembrane and intracellular kinase domains that can be accurately modeled in mouse Kit (Fig. 2e). Next, we used AlphaMissense and SIFT (sorting intolerant from tolerant) 4G to determine whether H2M modeling could also help predict variant pathogenicity. Increasing the flank size threshold restricted the H2M dictionary to the highly conserved transmembrane and intracellular kinase domains, which harbor mutations with higher AlphaMissense pathogenicity scores (Extended Data Fig. 4a–d and Supplementary Table 6). We also observed a strong correlation between SIFT 4G scores for human–mouse hotspot missense mutation pairs (Fig. 2f). These observations suggest that mutations in regions with high flank sizes are more likely to have a conserved functional impact.

Somatic mutations in cancer cells can generate tumor-specific epitopes that can be presented by HLA alleles (H2 in mice) and targeted by immunotherapies24,25. This strategy is constrained in part by the limited catalog of targetable neoantigens identified to date24,26. Although mouse models can facilitate prescreening and validation of putative neoantigens found in humans27, the predictive potential and functional conservation of mouse-derived immunogenic mutations in human systems remains underexplored. We hypothesized that H2M could be used to predict and map immunogenic mutations between humans and mice. To test this, we used H2M to determine whether known immunogenic human mutations can produce peptides predicted to be recognized and presented by homologous human and mouse major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II molecules. We first retrieved 642 human mutation-derived and experimentally validated MHC-I-bound neoantigens from TSNAdb version 2.0 (ref. 28; Fig. 2g). We then used H2M to generate murine versions of the human neoantigens, identifying mouse equivalents for 300/642 cases, and NetMHCpan4.1 EL29 to predict MHC-I mutant peptide binding and presentation across the two species. Over 60% of peptide pairs were predicted to be presented by at least one MHC allele in both species (Fig. 2g). This includes the EGFRT790M missense mutation, a recurrent lesion in persons with lung cancer30,31 known to produce functional T cell epitopes. Notably, restricting our analysis to the H2-Kb and H2-Db MHC-I alleles (expressed by C57BL/6 mice32) also identified a significant proportion of overlapping immunogenic peptides (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). These analyses support the utility of H2M to identify functionally conserved neoantigens across species and underscore the value of GEMMs to study human neoantigens in vivo.

We then tested whether we could simulate the process of discovering potential human MHC-I neoantigens using mouse tumor samples. We leveraged the species-agnostic nature of H2M to assemble an ‘M2H’ pipeline to analyze mutation data from DNA sequencing of mouse tumors33,34 (Fig. 2h). We identified 246 mutations in mouse protein-coding genes predicted to generate up to 3,991 neopeptide pairs in mouse and human cells expressing equivalent mutations (Fig. 2h, Extended Data Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 7). Many of these have not been recorded previously in the Immune Epitope Database30, suggesting that they may be tumor-specific neoantigens. High-throughput methods such as EpiScan35 and TCR-MAP36 can be used to interrogate candidate mutations predicted to generate immunogenic peptides. Sophisticated GEMMs such as KbStrep mice37 could be used for in vivo studies of high-priority antigens. Together, our results establish the potential of integrating cross-species computational analysis with mouse models to discover, predict and evaluate the immunogenicity of disease-associated mutations to accelerate neoantigen discovery and support personalized medicine efforts.

Paralogs have important roles in normal and disease contexts in part because of functional buffering32. They can also exhibit functional divergence and specialization, as well as paralog-specific mutational patterns and frequencies that vary by tumor type. Whether different paralogs exhibit functionally distinct mutational patterns and their impact on cancer phenotypes and treatment responses remain unknown. We reasoned that H2M could enable high-throughput analysis of paralogous mutations by integrating computational searching of mutation equivalents between gene paralogs and different species with precision genome-editing technologies19,32,38,39. To test this, we retrieved recurrent cancer-associated single-nucleotide variants from AACR-GENIE, filtered them through a literature-curated compendium of human paralog gene pairs33 and used H2M to computationally model the mutations in another gene paralog (Extended Data Fig. 6a). This resulted in a catalog composed of 10,211 paralogous mutation pairs (16,225 in total) (Extended Data Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 8).

As a proof of concept, we focused on the SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 paralogs, which respectively encode for the BRG1 and BRM mutually exclusive subunits of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex40. Cancer-associated SMARCA4 mutations are more frequent relative to SMARCA2 mutations, a pattern that also holds true for the ARID1A/ARID1B paralogs. AlphaMissense scores of paired SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 variants are significantly correlated (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Table 9). The most pathogenic mutations are located in the ATPase and the HSA domains in both proteins (Extended Data Fig. 6c). The impact of each SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 variant and whether this varies depending on the affected paralog remains unknown. For instance, the SMARCA4R1192C mutation is a statistically significant hotspot and classified as likely oncogenic in OncoKB40,41,42. H2M mapped this variant to SMARCA2R1162C and both substitutions are in the ATP-binding pocket (Fig. 2j). These substitutions receive high AlphaMissense pathogenicity scores (Fig. 2i), yet clinical observations documenting the effects of R1192C or other SMARCA2 mutations remain scarce.

To develop a framework to address this problem, we leveraged our mutation catalog to design a base-editing library containing >52,000 unique gRNAs targeting 4,740 paralogous mutation pairs19 (Supplementary Table 8). Some paralog-targeting gRNAs may target the same paralog pair and introduce the same mutation. Indeed, we found 574 gRNAs targeting 50 genes that could engineer 175 unique paralog mutation pairs with base editing (Supplementary Table 9). Thus, H2M can integrate cross-species paralogous gene-level and mutation-level analyses to identify guides for combinatorial paralog mutagenesis. These types of mutations are predicted to exhibit a strong functional correlation, as indicated by highly correlated AlphaMissense pathogenicity scores (Fig. 2k). These results underscore the potential of integrating cross-species genomic analyses with precision genome-editing tools to dissect the individual and combinatorial effects of paralogs.

The structured framework provided by H2M extends the alignment of genetic information from static sequences to dynamic sequence changes. While the mouse reference genome used by H2M is primarily based on the workhorse C57BL/6 strain, H2M also supports reference genomes from any species, enabling straightforward extension of variant modeling to any other mouse strain or species with available genomes. We envision that H2M will open the door for systematic cross-species functional studies of variants (including paralogs) and inform the development and benchmarking of new physiologically relevant and genetically diverse animal models. These studies would provide critical mechanistic insights into how genetic variation shapes organismal physiology, phenotypic heterogeneity and disease.