When you make a purchase through links in our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

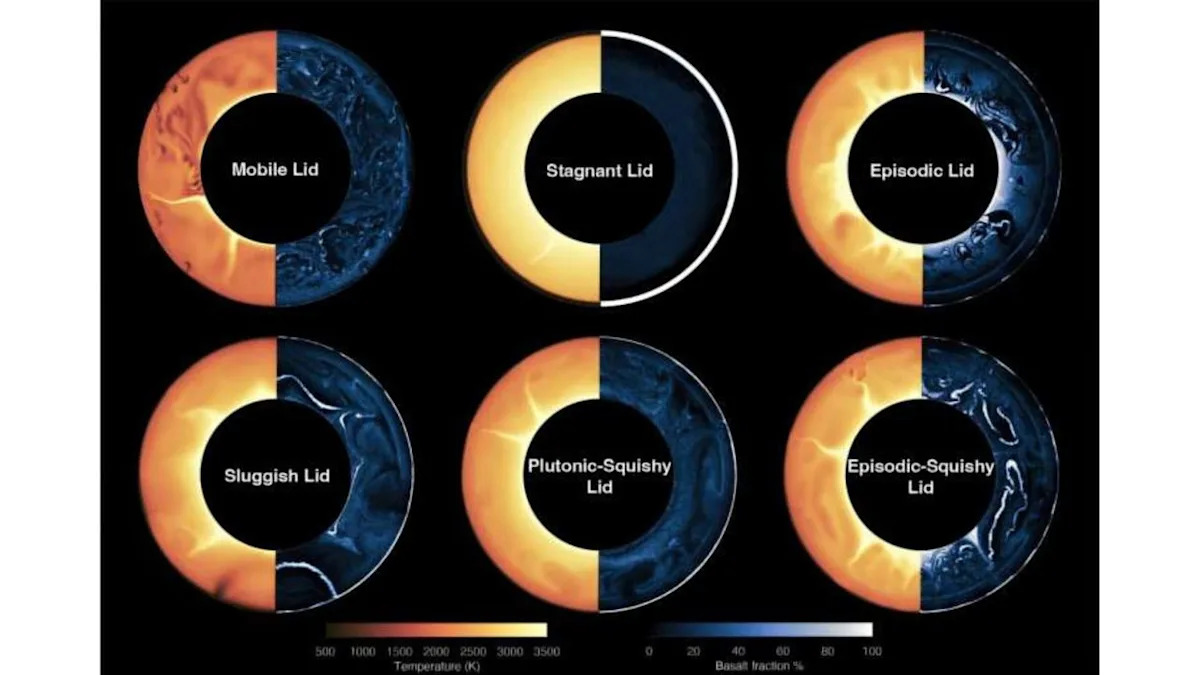

Six simulation snapshots showing different tectonic regimes of terrestrial planets, including a new “episodic soft lid.” | Photo: Nature Communications (2025)

A newly identified tectonic “regime” could rewrite our understanding of how rocky worlds evolve, scientists report in a new study.

The results may help explain why Earth became geologically active while Venus remained stagnant and scorching, which could have consequences for our understanding what makes a planet habitable.

When researchers used advanced geodynamic modeling to map a variety of planetary tectonics Modes—distinct patterns that describe how the planet's outer shell deforms and releases heat under different conditions—they discovered a missing link they called the “episodic-soft cap.”

This striking new theory offers fresh insight into how planets switch between active and inactive states, thereby changing scientific assumptions about planetary evolution and habitability, the team said in statement explanation of the study.

Tectonic regimes influence a planet's geological activity, internal evolution, magnetic field, atmosphere, and even its potential to support life. Episodic-soft lid is based on the traditional division between plate tectonics or moving lid regimes (as on modern Earth) and stagnant lid behavior (as Mars). It describes a state in which the planet's lithosphere changes cyclically between relatively quiet periods and sudden bursts of tectonic movements. Unlike the classic stagnant lid, this regime allows periodic weakening caused by intrusive magmatism and regional delamination, temporarily softening the crust before it hardens again.

According to the researchers, this constant and sudden behavior may be the missing link in the early evolution of the Earth. Models suggest that the Earth may have gone through a “soft lid” phase that gradually prepared it lithosphere for complete plate tectonics as the planet cools.

The results also help clarify the “memory effect” – the idea that a planet's tectonic behavior is determined by its past – showing that as a planet's lithosphere weakens over time, as has happened with Earth, transitions between tectonic states become much more predictable.

By mapping all six tectonic regimes under different physical conditions for the first time, the team produced a comprehensive diagram showing likely transition paths as the planet cools.

“Geological evidence suggests that tectonic activity on the early Earth matches the characteristics of our newly identified regime,” study co-author Guochun Zhao, a geologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in a statement. “As the Earth gradually cooled, its lithosphere became more prone to destruction by certain physical mechanisms, ultimately leading to today's plate tectonics. This is a key piece of the puzzle explaining how Earth became a habitable planet.”

The episodic soft cover may also shed light on long-standing mysteries of Venus. Although Venus is roughly the same size as Earth, it lacks clear evidence of plate tectonics, instead displaying volcanically altered terrain and distinctive features called coronae. The new models replicate those of Venus by placing the planet in an episodic or plutonic “soft lid” regime, where magmatism and mantle plumes periodically weaken the surface without creating true slabs.

“Our models strongly link mantle convection to magmatic activity,” study co-author Maxime Ballmer, assistant professor of geodynamics at University College London, said in a statement. “This allows us to consider the long geological history of Earth and the current state of Venus within a single theoretical framework, and also provides a critical theoretical basis for the search for potentially habitable Earth analogues and super-Earths beyond our solar system.”

Because tectonics controls how water and carbon dioxide circulate through a planet's interior and atmosphere, understanding how the lithosphere weakens and transitions between regimes occurs can help scientists assess which distant worlds might support stable climates or even life, and make decisions about observing targets for future missions.

The conclusions were published November 24 in the journal Nature Communications.