Matthew KenyonTechnology reporter, Delft, Netherlands

The last test was rough. Maarten Logtenberg wielded a sledgehammer, which simply bounced off the sample, barely leaving a scratch.

After two years of experimentation, the material was finally right: a special blend of thermoplastics and fiberglass that is durable, does not require additional coating to protect from sunlight, and is resistant to pollution and marine growth.

“The ideal base,” says Mr. Logtenberg, “on which to 3D print a boat.”

Boats must withstand the unforgiving nature of the marine environment. This is one of the reasons why shipbuilding is a notoriously labor-intensive business.

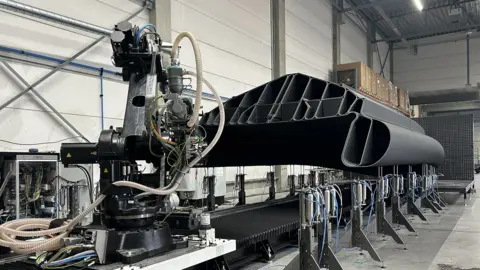

But after months of tweaking the chemistry, it took just four days for the first frame to come off the printer at the new plant run by Mr. Logtenberg and his colleagues.

“We automate almost 90% of the boat building process, in a very short time,” he says.

“It usually takes several weeks to build the shell. Now we print it every week.”

This is the story that 3D printing has long promised. A fast, labor-saving production process that significantly reduces costs.

These promises have not always been delivered, but Mr Logtenberg is convinced that it is in the maritime sector that 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, can play a transformative role.

Mr. Logtenberg is the co-founder of CEAD, a company that designs and manufactures large-format 3D printers from its base in the Dutch city of Delft.

Until now, its business had been to provide printers for others to use, but with a background in shipbuilding, CEAD decided to get into manufacturing as well.

“3D-printed boats have yet to be accepted by the market,” says Mr. Logtenberg.

“People are not going to invest and then just hope the market will develop. They prefer to buy capacity first. [So] Instead of just building cars, we're going to do it ourselves.”

ALLOW

ALLOWTraditional fiberglass boat building requires mold making and significant hand work to ensure the vessel is strong enough.

In additive manufacturing, the work is already done at the design stage, creating the software and the printer itself (which is labor intensive).

3D printers work by creating tiny layers of base material to create a predefined digital design.

Each layer is then linked to the previous one, allowing you to create a single, seamless object.

During the production phase, as long as the base material is supplied, little or no human intervention is required.

The design can also be adjusted without the need for major changes during the assembly process.

Most 3D printing occurs on a relatively small scale: dentistry is one area where it has had a major impact. Building a boat that can perform in real-world conditions is another challenge.

CEAD's largest 3D printer is nearly 40 meters (131 feet) long. A client in Abu Dhabi used it to print an electric ferry.

And within 12 months of operation at the Maritime Application Center in Delft, they have already built a prototype of a 12-meter RIB-like fast boat for the Dutch Navy.

“Usually when the Navy buys a boat, it takes years before they get it, and they pay a fair amount of money,” Mr. Logtenberg says.

“We did it in six weeks and on a very tight budget. And we can learn from that and build another one in six weeks and even rework the first one.”

Another fast-growing area is the use of unmanned vessels – maritime drones. CEAD recently took part in trials with NATO special forces, during which the drones were assembled on site in a matter of hours and their design varied depending on operational requirements.

The ability to move production makes 3D printing incredibly flexible, says Mr. Logtenberg.

Even a reputable printer can be transported in a shipping container and delivered much closer to the end user.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s a small 6m long work boat or a 12m long military boat. The machine will simply handle everything as long as we have a design.

“The only transport we need is the base material, which comes in big bags, and transporting it is very efficient compared to a boat.”

Matthew Kenyon

Matthew Kenyon Rough idea

Rough ideaNot far from CEAD, in the port city of Rotterdam, Raw Idea and its Tanaruz brand are aiming to have a similar impact on the entertainment market, especially in the rental market.

“Consumers are hesitant [because of the novelty]but the rental market is really buoyant,” says Joyce Pont, managing director of Raw Idea.

“It’s marketing, you can go on social media and say, ‘We have a 3D printed boat,’ and everyone will want to see and touch that boat.”

Another benefit is that Raw Idea uses a mixture of fiberglass and post-consumer recycled plastic (soda bottles, etc.).

This is one of the reasons why the price is now comparable to a traditionally built boat, as it costs more to purchase recycled material.

But Ms Pont says scale and flexibility will significantly reduce costs.

“I'm convinced that in five years, 3D printed boats will take over the market for fast boats, like work boats, like speed boats,” she tells me.

The maritime industry is heavily regulated, but certification bodies have to keep up with innovation.

Both RAW Idea and CEAD are interacting with European regulators in near real time as they use new materials and new ideas to produce vessels that cannot be compared to what came before.

3D printing is often hailed as a revolutionary technology, but it doesn't always live up to those expectations.

Mr Logtenberg says this is because the method is used in a variety of contexts.

“It's all seen as one thing, but there's metal printing, polymer printing or large-scale printing, all these different applications.

“There are a lot of applications that haven't succeeded because they weren't competitive enough, but there are a few where it actually happened and are being used.”

Additive manufacturing is increasingly being used in shipping, but in technical niches rather than entire hulls.

How far can 3D printing go in the marine world? We are a long way from having entire ships printed at once.

Joyce Pont is skeptical that this moment will come in the foreseeable future – she views the construction of superyachts and other similar vessels as a “craft” that cannot be automated.

But Mr Logtenberg is more optimistic.

“A year ago, when I created a 12-meter boat, I didn’t even expect this,” he says.

“Traditional shipbuilding is done in modules. It may be a decade or two before we fully print [a ship's hull]because there will be more need for material research.

“But thermoplastics are being developed and improved all the time. Of course, machines, everything needs to be scaled, but why not?”